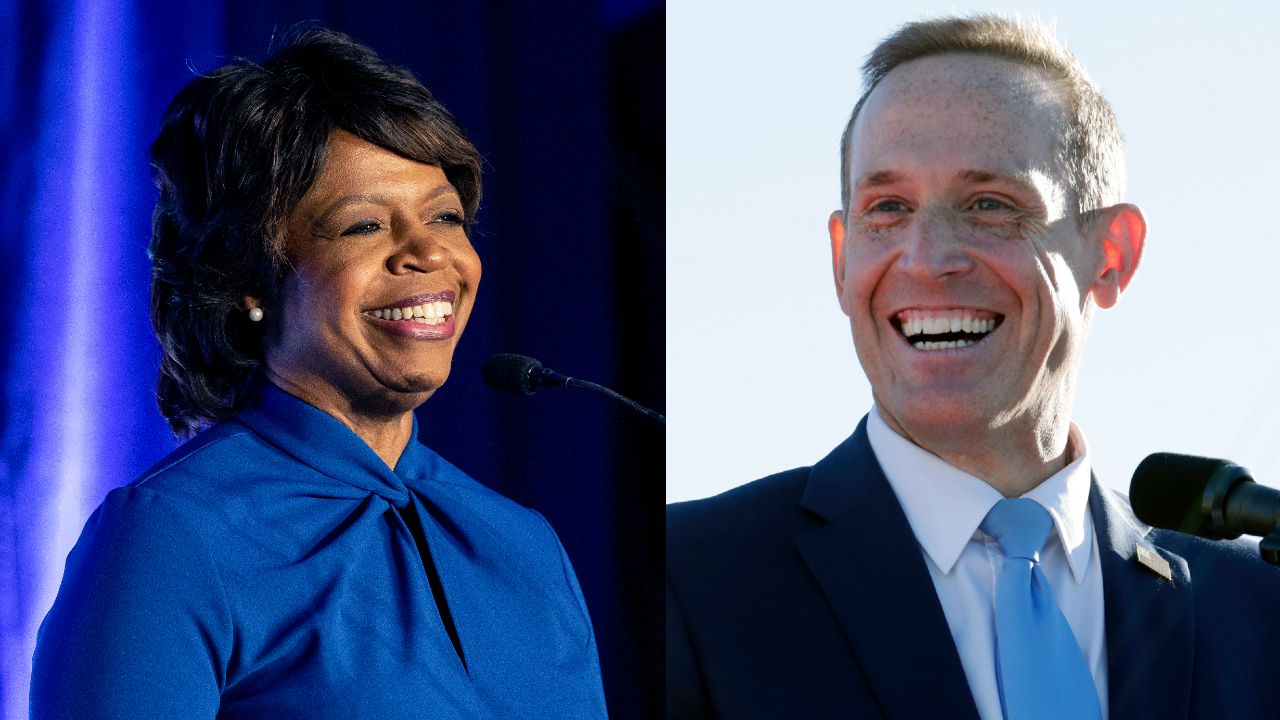

With less than a month to go before the midterm elections, polling shows Republican Ted Budd and Democrat Cheri Beasley running neck-and-neck for North Carolina’s open seat in the United States Senate.

It’s the season for “horse race” coverage of big elections, where reporters and pundits cite polls and use sports and military metaphors to describe where things stand. The lines are clearly drawn at this point in the election between the Republican congressman and the Democratic former chief justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court.

Budd, with former President Donald Trump’s endorsement, is the Trump “America first” candidate focused on immigration, blaming the Biden administration for the economy and has filed a federal bill to restrict abortion access. Beasley, for her part, is a vocal supporter of abortion rights, wants federal action to give more people health care, and also says inflation and immigration are big problems, but disagrees with Budd on what to do about them.

RELATED: Beasley-Budd debate: Senate candidates tackle inflation, abortion, immigration

North Carolina is a deep purple state. Two years ago, voters in the Tar Heel State went for Trump in the presidential election and at the same time gave Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper a solid reelection victory. But in recent Senate races, Republicans in the state have pulled out wins despite close polls and higher fundraising by Democrats.

It’s hard to know what to make of polling anymore. Pollsters mostly got it wrong ahead of the 2016 presidential election and overestimated Joe Biden’s lead in 2020.

Spectrum News 1 spoke with two of North Carolina’s top academic pollsters, Meredith College’s David McClellan, director of the Meredith Poll, and Martin Kifer, director of High Point University’s Survey Center and the HPU Poll. We asked them what to make of the polls this year and how people should be reading through this deluge of data.

“Make sure they are being very transparent about their methods,” Kifer said.

A good political poll will be up front about who they are calling and surveying online — how they are reaching those people, how diverse is the sample, what are they doing to weight any results, what are the questions and in what order they are asking them, both Kifer and McClellan said.

Avoid the candidates’ own polling, McClellan said, and look to academic polls and other organizations that have a good track record.

“The polling average they’re putting together, that can help. That’s one way we’re addressing these sampling errors issue,” Kifer said. Websites like FiveThirtyEight and RealClearPolitics aggregate polls, weighing each and giving an average.

When McClellan started his career in polling, it was all done by phone, randomly calling landlines. But technology and society have changed and that does not work anymore.

“Now, in the 21st century, we have found that doing phone calling to collect our data is a difficult thing to do,” he said. “A lot of people, whether they have cell phones or landlines or both, they don’t answer their phones.”

“We’re trying to get the most representative group of respondents we can get,” he said. When he started the poll in 2015, they were calling but having trouble getting young people, people of color and people who lived in urban areas.

The Meredith poll now uses what’s called “mixed mode,” a combination of phone calls and online respondents. Those online respondents have to sign up to participate in polls run by third-party companies that have a big pool of people who do lots of online surveys, making “a couple of bucks each,” McClellan said.

High Point University has moved to doing all online panels for polls, Kifer said.

In the 13 years Kifer has run the HPU Survey Center, he said it’s gone from being able to reach almost everyone on landlines, to people getting cell phones, and now most won’t even pick up their phone for an unknown number.

“That affects a lot of how we do our jobs,” Kifer said, and it can also affect the results. “We have to be very careful about who is in the sample.”

Being able to represent North Carolina’s entire population means making sure to get enough diversity in age, race, income, education level and other factors. In political surveys, pollsters also have to choose between talking to all adults, registered voters or people who say they are likely to vote in the next election.

For political polls, McClellan said he targets people who say they are likely to vote in the next election.

Once they have the responses, McClellan said they have to weight the results to balance things out.

“If we have way too many people with a college degree, say, in our online sample, we will weight the results for people who have less than a college degree,” he said. Using weighting and statistics, McClellan said they can make the results looks like the total population of North Carolina.

Polls are based on statistics, and the margin of error or confidence interview is an important part of gauging how accurate the poll is.

If a poll had Budd up by 1 point, but has a 3% margin of error, that means Budd falls anywhere from being up by 4% or down by 2%. The margin or interval means the candidate falls anywhere within that interval.

The margin of error comes from the number of people included in the poll.

McClellan said he aims to get between 800 and 1,000 respondents on each poll, which makes the margin somewhere from 2.5% to 3.3%.

He said people will ask him why the poll doesn’t get 2,000 or 3,000 responses.

“Sometimes it comes down to diminishing marginal returns,” he said. “The difference between 1,000 people in a sample and 2,000, because of statistics, it doesn’t reduce your margin or error or confidence interval as much as you might think.”

Doubling the number of people, and the added costs and time involved in the bigger survey, could bring the margin down from 2% to 1.7%.

Kifer agreed with McClellan, saying he aims to get responses from 1,000 people in the HPU Poll.

“Generally speaking, the more people you talk to, the more you can reduce that error,” Kifer said.

“I tell people when I release my poll results: This is not a forecast of what will happen,” McClellan said. “My poll was released five weeks before the General Election was going to be held. Does this mean Ted Budd will win by three-tenths of 1%?"

He describes polls as a “snapshot in time” of how people are feeling.

McClellan said he has three pieces of advice when it comes to reading polls: First, look at the method a poll uses to collect information. Make sure they have the way to ask the right people the right questions. If it’s solely a telephone survey, they may not be reaching everyone they need to talk to.

Second, look at the margin or error or confidence interval, he said. “It says that our results are within a range of possible results,” he said. If a poll has a high margin of error, like 6%, that means they did not talk to enough people.

Third, look at the questions and how they are worded. “There are many ways to manipulate your responses,” McClellan said. “Ask leading questions, see which are questions that are getting people thinking about a topic in a certain way.”

“Read through the questions before the responses to see. Are there any questions that you might answer one way simply because of the wording of the question, not because that’s how you feel about the topic or the candidate?” he said.

He said people should read a variety of polls and look at poll-aggregators that average results over multiple polls.

Transparency is also important. Polls should be open about who they talked to and how, how the poll was weighted and whether the report includes every question and every response.

Kifer echoed the need for transparency in good polls.

“Search out transparency from those surveys about how they’re collecting their information, when it was collected, who they were interviewing and everything about the poll itself,” Kifer said.

McClellan said he generally avoids polls from political campaigns and looks to North Carolina’s academic polls. He complimented Civitas, a partisan organization, for doing good polls. On the national level, he said he looks to organizations like Gallup and Pew.

“I guess we will know something after Election Day,” Kifer said. The polls, he said, show, “it’s pretty close, but those errors might not look right.”

He said that with the polling so close in recent weeks, the surprise would be if Budd or Beasley won by a wide margin. Either way, North Carolina should know who its next senator will be after Election Day on Nov. 8.