This is part one in a three-part series on offshore wind in North Carolina.

Over the next decade, the offshore wind industry could transform the way North Carolina gets its power. It could also mean big investments and major changes for the economy.

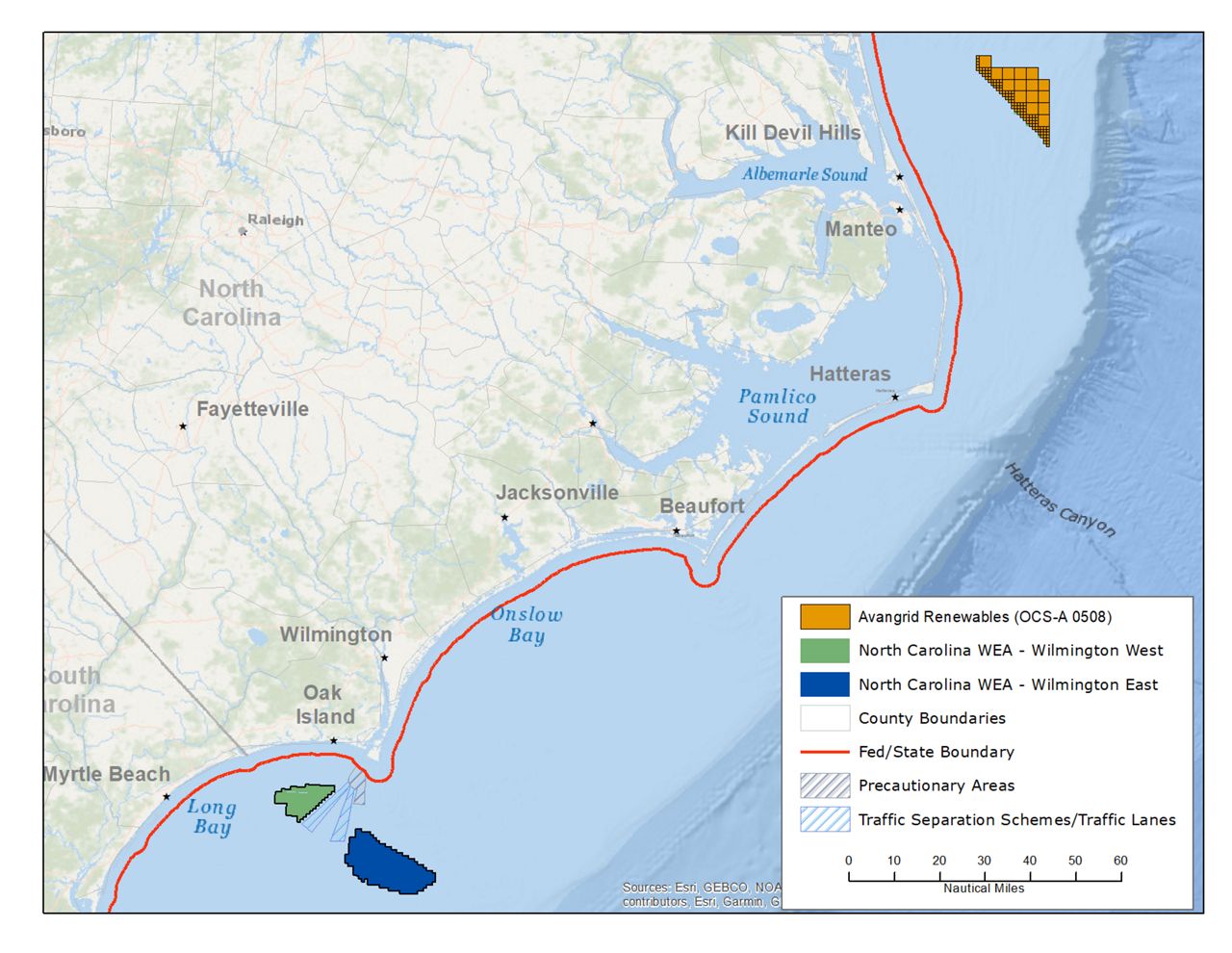

One offshore wind farm area, off the Outer Banks, is already leased, and there are plans to install 2.5 gigawatts worth of wind turbines starting 27 miles off the coast. The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management just opened to window for companies interested in leasing another area off Wilmington. That area could potentially generate up to 1.5 gigawatts of power.

To put that in perspective, an average nuclear power plant generates 1 gigawatt, according to the Department of Energy.

More than 25 miles out to sea from Norfolk, Virginia, two massive wind turbines already tower over the ocean. These turbines are just a test for a much bigger offshore wind farm that will, if all goes to plan, generate 2.5 gigawatts of electricity for Virginia. That's enough energy to power about 700,000 homes.

The scale of offshore wind turbines is almost too big to imagine. The towers planned for Dominion Energy project stand 800 feet above the ocean floor. The blades themselves are about 350 feet long. These big offshore wind projects take decades to complete, from finding the right spots to actually building the turbines. The scale of the investment it takes is hard to imagine too.

The North Carolina Commerce Department estimates the state could be positioned to tap into more than $100 billion in investment expected from the offshore wind industry in the United States in the coming years. The industry needs somewhere to build all the parts that go into the turbines, specialized ships, ports to work out of, and then there’s years worth of construction and maintenance.

This year, North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper set a goal of developing 2.8 gigawatts of offshore wind energy by 2030 and up to 8 gigawatts in the next two decades.

The big wind farm in the works off the Outer Banks, dubbed the Kitty Hawk project, is the first of its kind in the mid-Atlantic. Avangrid, the company leading the Kitty Hawk project, doesn't have a deal yet to sell the power from the offshore wind farm off the Outer Banks, but it may go to Dominion Energy in Virginia.

Most of the work for the Kitty Hawk project, and most of the jobs and investment so far, has been in the Norfolk area. But if Virginia’s experience is any indication, offshore wind could be big business for North Carolina too.

Just last week, Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam announced a company planned to lease 80 acres in the Portsmouth Marine Terminal to build the giant blades that will turn atop the offshore wind turbines.

The Siemens Gamesa Renewable Energy facility will create more than 300 jobs and mean a $200 million investment for the state.

“Virginia is building a new industry in renewable energy, with more new jobs to follow, and that’s good news for our country,” Northam said. “This is good news for energy customers, the union workers who will bring this project to life, and our business partners.”

Virginia may be ahead in offshore wind, but North Carolina is moving to attract the same kind of investment.

Hitachi Energy is one of the big players in offshore wind, what the state Commerce Department calls a “potential anchor company” for the industry in North Carolina. The company’s North American headquarters is on N.C. State University’s Centennial Campus in Raleigh.

Hitachi designs and builds the systems to get energy from the offshore wind turbines onshore to the power grid and into homes and businesses.

“You really need a very large and strong support chain with a lot of highly skilled jobs. So from an economical point, in particular for North Carolina, it could be very beneficial,” said Anthony Allard, head of the company’s North American operation.

Hitachi has about 400 employees based in Raleigh, mostly engineers and researchers, he told Spectrum News 1. The company has had a presence on the N.C. State campus since 1992, he said.

The jobs the offshore wind industry could bring to North Carolina run the gamut from high-end engineering jobs to construction and manufacturing.

For the North Carolina Department of Commerce, it’s all about the supply chain. Building all the things that go into an offshore wind project can be big business. The industry needs a power grid and transformers, it requires special ships, components and tools. With North Carolina’s long history of manufacturing, the state’s political and business leaders say there’s no reason those things shouldn’t be made here.

It’s not just giant turbines and blades, either. Tucked into an industrial area of Sanford, about 45 minutes southeast of Raleigh, SpanSet manufactures specialized slings to pick up the very heavy components that go into building wind turbines. It’s the modern and highly technical version of North Carolina’s historic textile industry.

The factory floor hums with sewing machines. Workers weave and sew straps that can lift hundreds or thousands of pounds. The company, based in Europe, makes very specialized textiles that are essential to the wind industry, which needs the straps to lift the massive components to assemble wind turbines.

SpanSet has about 35 employees at the facility in Sanford, said Ed Connor, president of the company’s operations in the United States. He said SpanSet buys some of the textiles to make the specialized straps from a manufacturer in Greenville and then workers assemble the straps in Sanford.

“This is a perfect example of an industry that can continue to grow and bring the type of jobs that are paying living wages, providing opportunities for people,” Cumberland County State Senator Kirk deViere said recently on a tour of the SpanSet facility.

Conner said the straps made in Sanford can lift up to 100,000 pounds. The company just helped lift components for a massive turbine in Oklahoma that weighed 500,000 pounds.

“The size of the windmills has become huge,” Connor said. “The wind industry is getting bigger and bigger.”

At the back of SpanSet’s warehouse sits what looks like a giant steel hook, taller than Connor. He said it’s a gripper, designed to go on a crane and delicately pick up sections of massive turbine towers and lower them into place.

For offshore wind, they have to use what he called “jack-up ships” to put the towers together at sea. One problem the offshore wind industry is facing is that there are no ships flagged to the United States that can do this kind of specialized work.

“These components are so big that once they’re manufactured, they never get very far from the water. You can’t move a 107-meter long blade by rail,” said Rich Baldwin, a consultant with Lloyd’s Register who helped prepare the analysis for the state Commerce Department.

But, he said, “The offshore wind industry isn’t going to just be on the coast.” It will include companies like Hitachi doing engineering work in Raleigh and SpanSet making specialized straps in Sanford.

Much of the industry though, will be on or near the coast.

SpanSet CEO Connor said the ports could be a problem for developing North Carolina’s offshore wind energy. But they could also be an opportunity.

The Commerce Department’s report looked at North Carolina’s ports compared to neighboring states.

The best ports in the mid-Atlantic for offshore wind development are Norfolk and neighboring Portsmouth. That’s where they just announced the new facility to build blades for the offshore turbines.

North Carolina’s two biggest ports, Wilmington and Morehead City, scored well, Baldwin said, but not as well as the ports in Virginia. He said both have opportunities to set up staging or manufacturing for wind projects.

In Morehead City, there’s a property near the port called Radio Island that could be converted into a staging area, the report notes.

“As the industry matures, this facility could very easily pivot to a manufacturing facility,” Baldwin said earlier this year when the report was released.

In Wilmington, there’s an old railroad manufacturing facility not far from the port that could be converted for staging big parts or manufacturing.

A little farther south, Baldwin said, “is just a really interesting opportunity” near the mouth of the Cape Fear River in Brunswick County.

He said the site, which is already owned by the Ports Authority, could be the only potential site for a “mega-port” on the East Coast. The site is 600 acres and has the potential for manufacturing around the outside and staging area on the waterfront.

“The development of such a mega port could represent a significant game-changer in the U.S. and International (offshore wind) Supply Chain marketplace. With all of North Carolina’s other resources and assets (e.g., affordable housing, right-to-work status) discussed elsewhere in this report, the costs of Tier 1 components at this facility could be highly competitive with other states and countries,” the report said.

Ports in Morehead City or Wilmington, and potentially near Southport, would be well positioned long-term for other big offshore wind farms.

There are potential offshore wind areas off Wilmington and off the South Carolina coast.

“As the offshore wind market and development grows, we’re expecting to see more of this opportunity come closer to North Carolina,” said Mike Blanch with BVG Associates, another consultant that worked on the N.C. Commerce Department report.

“It makes sense to put new factories in new markets and that avoids the risks and costs of transport,” he said.

“North Carolina is a recognized leader in manufacturing,” said Andy Geissbuehler, also with BVG. “We need to be very active to make sure we’re moving fast enough to get an appropriate shore for North Carolina in this business.”

North Carolina already has major players like Hitachi, he said. If the state plays its cards right, “North Carolina could serve the whole East Coast,” Geissbuehler said. And this isn’t just a quick investment in the state and then these companies leave, this could be a long-term change in North Carolina’s economy. Wind farms last for decades.

“This is a very sustainable long-term business,” he said.

“Offshore wind power will help North Carolina create jobs and generate economic development while helping us transition to a clean energy economy,” the governor said when he set the state’s ambitious offshore wind goals in June.

“North Carolina’s national leadership in clean energy and manufacturing plus our highly trained workforce create a strong business environment for offshore wind supply chain and manufacturing companies,” Cooper said.

Editors Note: This story has been updated to correctly identify the offshore wind areas near Wilmington.