This is the third story in a three-part series on offshore wind in North Carolina.

The sheer scale of offshore wind is impressive: blades as long as football fields turn about over the ocean, mounted to towers up to 800 feet tall that are anchored on the ocean floor. Then multiply that by dozens or hundreds of turbines spread out over the ocean.

The size of the turbines is matched by the amount of time, money, science and engineering that goes into offshore wind farms. These projects take decades.

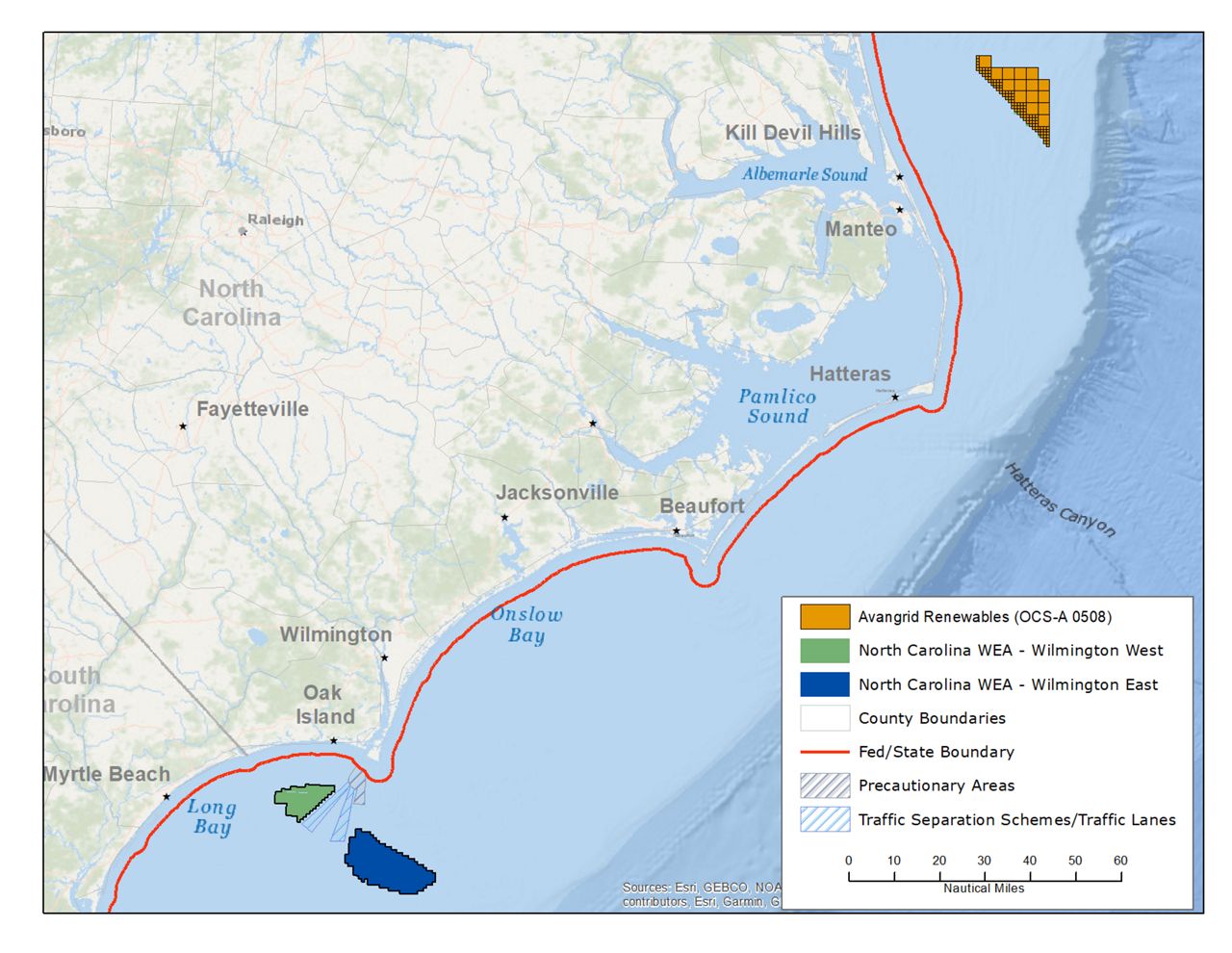

Off the coast of North Carolina, there are three designated offshore wind areas. Federal regulators have already leased one, called the Kitty Hawk project, about 27 miles east of Corolla. Another area, off Wilmington, will be leased next year, according to the Bureau of Offshore Energy Management.

If everything goes to plan, there could be two wind farms off the coast of North Carolina sometime over the next decade.

This year, Gov. Roy Cooper set a target to develop 2.8 gigawatts of offshore energy by the end of the decade and 8 gigawatts by 2040.

As a comparison, the average nuclear power plant generates about 1 gigawatt of energy per year.

That 2030 goal may actually be achievable if things stay on track. The company building the Kitty Hawk wind farm says that project could generate 2.5 gigawatts. Federal regulators say the area off Wilmington could potentially generate 1.5 gigawatts.

Beginning in the late 2000s, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill oceanographer Harvey Seim was part of the state task force charged with figuring out the best spots off the coast for offshore wind.

“We found that the wind field off North Carolina is pretty strong. It’s a good environment in which to do this,” Seim said.

The work to pick the spots took years. Seim said the group had to look at all different kinds of factors, including the wind, the sea floor, the depth of the ocean. They also had to look at conflicts with fishing and the military, and a range of potential environmental impacts.

Companies that do get offshore wind farm leases even have to scan the ocean floor for unexploded bombs and historic artifacts.

The state task force to identify potential areas for offshore wind farms was the first step to kick off the federal process. Once states pick the best areas, federal regulators with the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management take over to designate the areas for offshore wind and start the process of leasing them out.

The task force picked three areas, one off the northern Outer Banks and two off of Wilmington and Brunswick County on the southern end of North Carolina’s coastline. Those two areas are called Wilmington West and Wilmington East and are essentially on either side of the shipping lanes coming out of the Port City.

Seim said they looked at the entire coastline and there were other good possible offshore wind areas off Onslow Bay, between Wilmington and Morehead City, and Raleigh Bay, out from Ocracoke and Cape Lookout. But, for various reasons, those areas never advanced.

A project is already in the works for the Kitty Hawk site. The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management is putting up the Wilmington East area for lease now.

There may be a problem with the Wilmington West site, which is closer to shore than Wilmington East. That western site could be a calving ground for North Atlantic right whales, Seim said.

“The northern right whales, that’s a real problem,” he said, because ships could hit and kill the endangered whales.

”They’re slow moving, they like to be at the surface, their coloration is such that they’re almost impossible to see, even when they’re at the surface,” he said all the boats and shipping associated with building an offshore wind farm could do more damage to the species.

The task force looked at potential impacts on other animals, too. Birds and bats were of particular concern, Seim said.

“You build the wind farms in the wrong areas, you’re going to kill a bunch of birds and bats,” he said. “In general, I don’t think anybody’s found a strategy to warn those kinds of creatures to not run into the turbines.”

The strategy to avoid killing migratory birds and bats is to avoid building turbines in “flyways,” the routes they use during migration, Seim said.

He said there are some routes over the North Carolina coast that are heavily used during migration, so they picked areas away from those routes.

Off the coast of Virginia, Dominion Energy is monitoring birds and bats at its two test turbines, said Diego Tatias, who runs the day-to-day operations of the turbines for Dominion Energy.

“One of the advantages of being 27 miles offshore is that we’re not constantly being near birds,” Tatias told Spectrum News 1. “We’re far out and we don’t see that many bird species in the neighborhood.”

The Department of Energy last month awarded Duke University $7.5 million to lead a study on how offshore wind could harm birds, bats and marine mammals. The group includes 15 universities and organizations up and down the eastern seaboard.

Duke professor Doug Nowacek, who will lead the research, said there are still some major gaps in what scientists know about how these species move and behave in these areas.

“Our goal is to provide a long-term adaptive roadmap – a science-based toolkit – that industry and government agencies can use,” he said in a statement.

“Harnessing the incredible potential that exists within offshore wind energy is an essential piece of reaching a net-zero carbon future,” U.S. Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm said in a statement. “We must ensure that it’s done with care for the surrounding ecosystem by co-existing with fisheries and marine life – and that’s exactly what this investment will do.”

Infrastructure on land is another big factor in where to put offshore wind farms. Power companies have to be able to bring massive amounts of energy onshore and get it into the grid. That’s one of the main reasons, Seim said, power from the Kitty Hawk project is likely going to go to Virginia and not North Carolina.

Duke Energy doesn’t have the transmission lines in northeast North Carolina to bring the power back to the grid. But there is a way to connect into Virginia for the grid that serves areas to the north.

But Duke Energy does have more of that infrastructure in the southeastern corner of North Carolina, where it operates the Brunswick Nuclear plant.

Publicly, Duke Energy has been relatively quiet about any plans for offshore wind. In a short statement, a Duke spokeswoman said, “Duke Energy is committed to achieving our 2050 net-zero carbon emission goal, and transitioning our infrastructure towards cleaner, reliable energy resources that are affordable for our customers and communities.”

With the window opening for the lease of the offshore wind area off Wilmington, the state will learn a lot more about what the future looks like for offshore wind off North Carolina.

Once states identify the best offshore wind areas and federal regulators lease the areas, companies still have years worth of work to do on environmental studies and engineering before they can start building offshore wind turbines.