Offshore wind could mean big business and clean energy for North Carolina.

Spectrum News 1’s new series on offshore wind dives into the politics, business and science of harnessing ocean winds to power North Carolina.

Here are some of the central questions we set out to answer and what we found:

What are the state’s goals?

Over the summer, Gov. Roy Cooper signed an executive order setting offshore wind energy goals. The order calls for 2.8 gigawatts of offshore wind development by the end of this decade and 8 gigawatts by 2040.

One gigawatt of wind energy can power up to 300,000 homes, according to the Department of the Interior. An average nuclear power plant generates about 1 gigawatt.

On top of the governor’s wind power goals, the General Assembly recently passed a new clean energy bill that calls for shuttering dirty coal-fired power plants and replacing that energy generation with renewables like wind and solar.

The new law sets a target to reduce greenhouse gas emission from power generation by 70% at the end of this decade and be carbon neutral by 2050, based on 2005 levels.

What does it take to build an offshore wind farm?

From the first steps of selecting the best spots in the ocean for wind farms to actually getting power into the electrical grid, the process can take about 20 years.

Scientists have to find the best spots, regulators have to navigate impacts on things like fishing, the military and possible environmental impacts. Companies even need to scan the ocean floor to make sure there aren’t any historical artifacts or unexploded bombs.

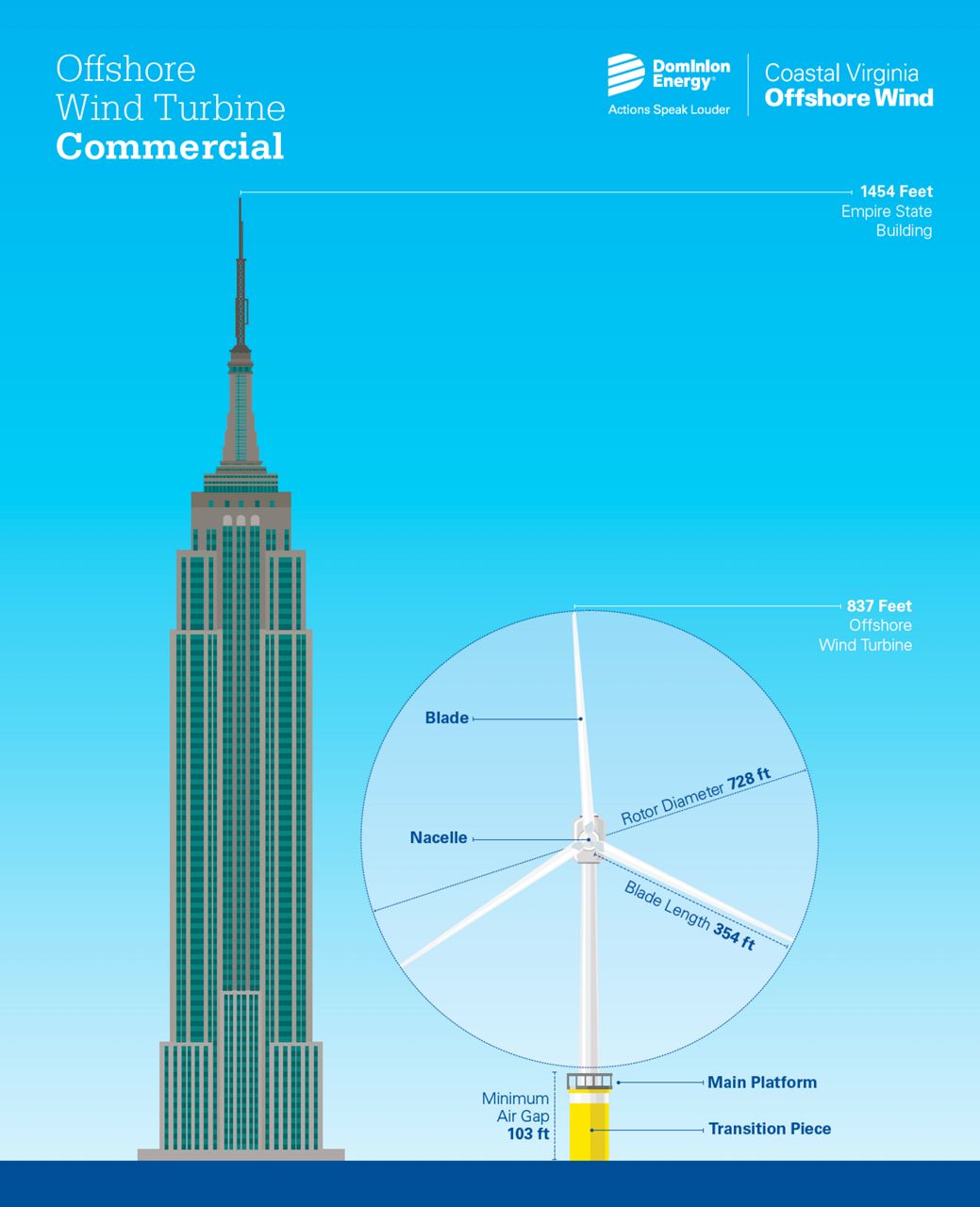

It’s taken more than a decade to get to the point where one company is almost ready to start building an offshore wind farm off the Outer Banks. But then there’s the matter of manufacturing the massive components, like turbine blades almost as long as a football field, and then assembling them all 20-plus miles out in the ocean.

Wind farms off the East Coast will likely all have 100 or more turbines, towering 800 feet above the ocean floor.

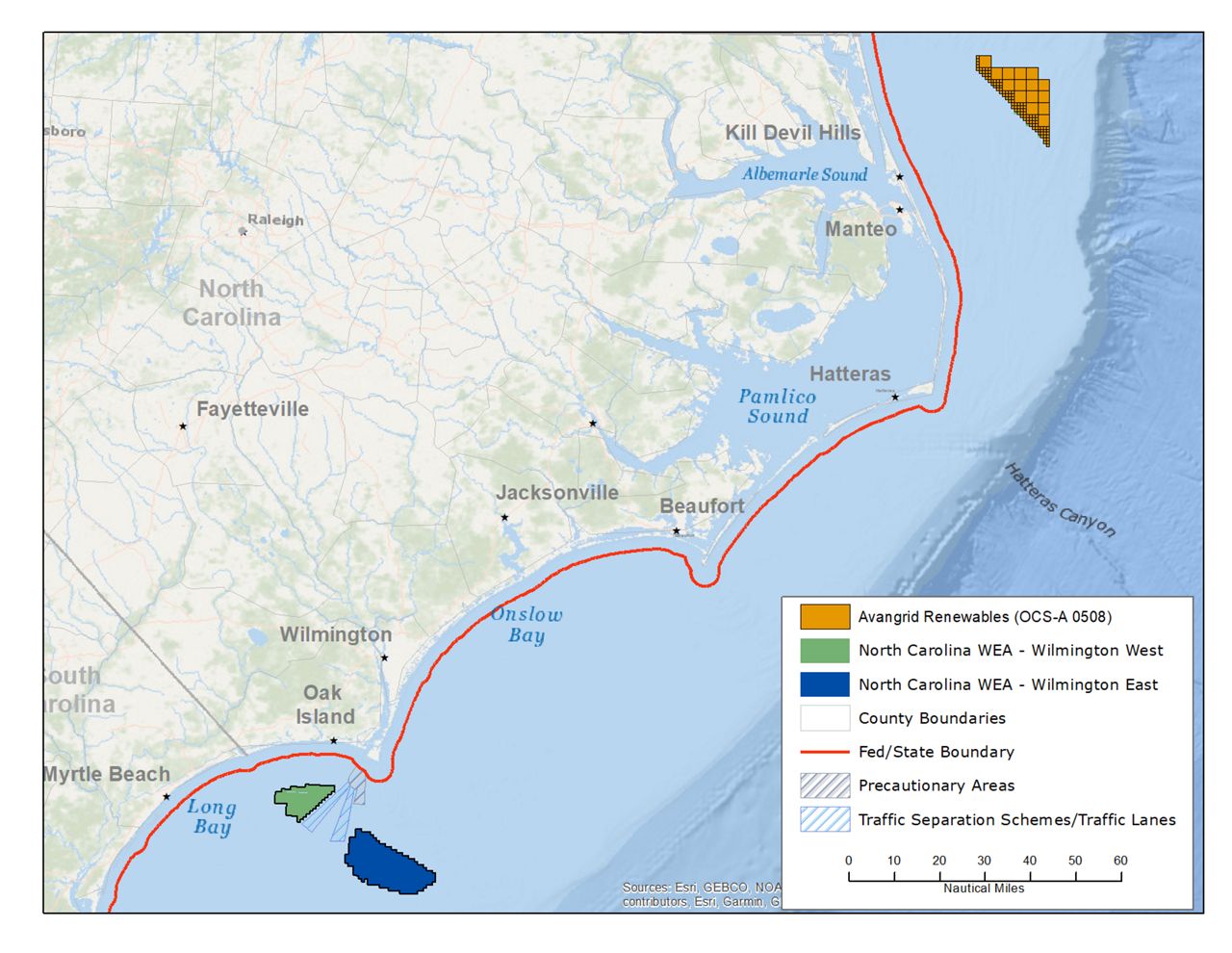

Where could offshore wind be built off North Carolina?

State and federal regulators have identified three offshore wind areas off the North Carolina coast. One, dubbed the Kitty Hawk project, is off the Outer Banks, 27 miles east of Corolla.

There are two areas off Wilmington and Brunswick County, on either end of the shipping lanes coming out of Wilmington. The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management is getting ready to lease one of those areas, Wilmington West.

The Wilmington East area may be part of the calving area for endangered northern right whales, which may pose problems for developing an offshore wind farm there.

What about whales and birds?

The biggest risk to whales with offshore wind farms is all the boat traffic and noise associated with construction out in the ocean. Northern right whales are notorious for moving slowly, hanging out at the surface and blending in well with the water. They’re hard to see and boat strikes could kill the endangered whales.

Wind turbines can kill birds and bats. The strategy so far is to look at migratory routes and build wind farms away from these “flyways.” There are no real strategies to warn birds and bats to stay away from the giant turning blades.

A team led by Duke University recently won a $7.5 million grant from the Department of Energy to study how to keep birds, bats and marine mammals safe around offshore wind farms.

When will we see turbines off the N.C. coast?

If all goes to plan, construction should begin on the Kitty Hawk project sometime in 2025, according to Avangrid. The company expects the wind farm to begin operation in 2026.

The project to the south, off Brunswick County, is likely years away. But we should learn more about that in the coming months as the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management gets ready to lease that area next year.