The public hearings before redrawing North Carolina’s political maps will wrap up at the end of the month, but it’s still not clear exactly how the process will work after that.

Every 10 years after the census, each state goes through a process of redistricting to set new electoral maps. In North Carolina, the ruling party in the General Assembly is in charge of creating new districts for congress and the state legislature.

The political and legal fights over North Carolina’s maps lasted most of the decade last time around, and the maps were just ordered to be redrawn one final time in 2019.

Republicans are still in control of the General Assembly this year, and the governor has no veto power over the maps. North Carolina will also be getting a new seat in Congress, but it’s not yet clear where that will be.

“What we have seen in past cycles of redistricting has been very much a behind-closed-doors dynamic, where consultants, data and technology have basically made redistricting a science,” said Michael Bitzer, a professor of political science and history at Catawba College, who just published a new book on the history of redistricting in North Carolina.

There are still a lot of questions about how the rest of the process will play out. That process is much shorter this year compared to previous decades because of delays releasing the census data needed to make the new maps.

The General Assembly needs to have the maps done and passed through the state House and Senate by early November because the filing deadline for the 2022 elections is Dec. 6.

“We know, in past cycles, the maps have been drawn behind closed doors with consultants. Is that dynamic going to play out again this year? Or are they going to at least presume to start to draw things in public even though they’ve got a good idea of how they want the district to look?” Bitzer asked.

“Going back to the 1980s, North Carolina was always kind of the epicenter of battles over redistricting,” he said.

A 2019 court ruling forced the General Assembly to redraw the maps in an open process, essentially in a big room where the public could watch the process.

“What we’re seeing now is at least a beginning sense of transparency based on the 2019 court case,” he said. “If they choose to be open, start the process after the hearings and actually see the maps being built, there will still be cries of partisanship, but the cries may not be as justified as what we’ve seen in the past.”

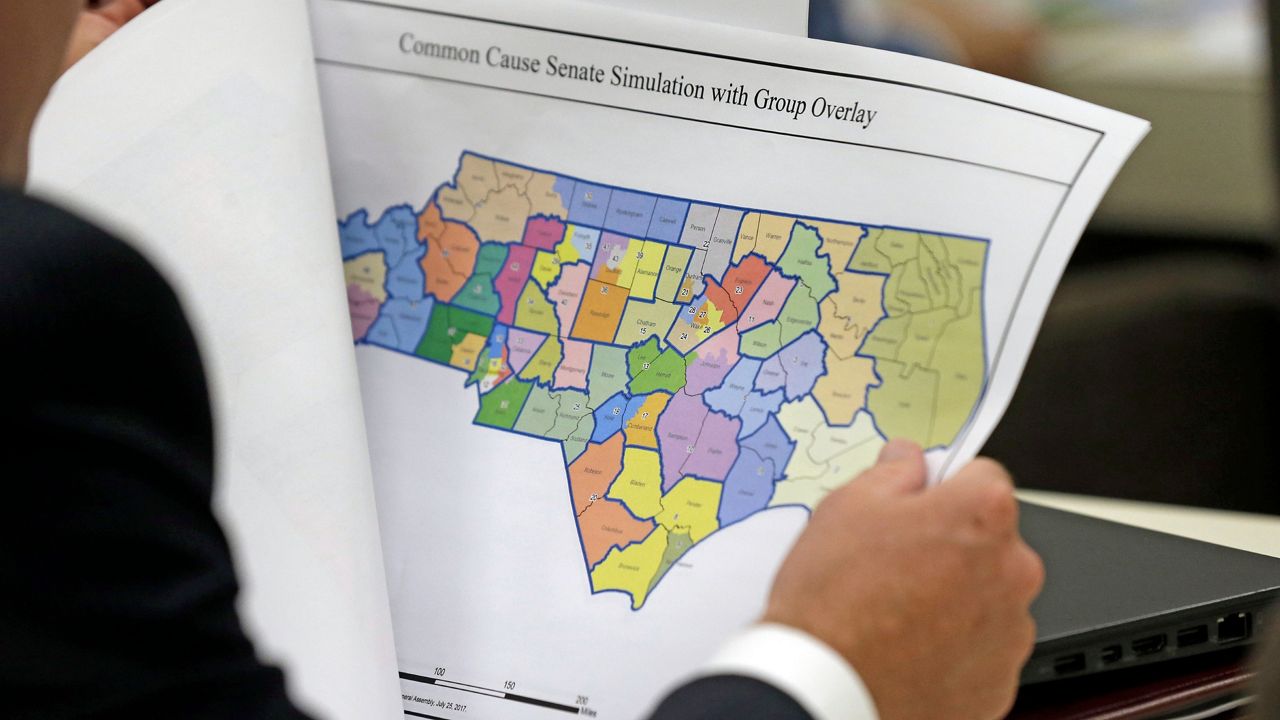

That court ruling came after a lengthy legal battle by Common Cause North Carolina and others, who sued the General Assembly over the maps.

Bob Phillips, the longtime executive director of Common Cause North Carolina, said he’s hopeful the process will be more open this year.

“Will we have the perfect transparency? No. Will it be better than it’s historically been? I hope so,” Phillips said.“Will we have the perfect transparency? No. Will it be better than it’s historically been? I hope so,” Phillips said.

“Two years ago, the courts basically said, legislature, you are going to have to redraw the legislative maps, we are going to require that you do it in the open, in a meeting room that was livestreamed,” he said. “That was refreshing.”

The process this year started with a series of public hearings across the state, but Phillips said the hearings should have been livestreamed online, and the public should be able to participate virtually.

He also said he was disappointed the General Assembly committee in charge of redistricting only has one public hearing scheduled for after the maps are drawn.

“Think of 2016 when North Carolina A&T, the largest historic Black university in the country, was split right down the middle,” Phillips said, pointing to a popular example of gerrymandering from another court-ordered redraw of the state’s maps.

People should get the opportunity to look at the actual maps and give feedback to lawmakers without having to all come to one public hearing in Raleigh.

“It’s far from being a pure transparent process. But we hope to see at least that this time, at a minimum, we hope to watch the maps drawn in a committee room where we can all watch and ask questions,” Phillips said. That would be similar to the court-ordered process in 2019.

“As long as you have lawmakers drawing their own districts, you’re never going to have a real pure transparent process for the public’s interest,” he said.

Common Cause and other groups around the country have been pushing to move redistricting out of the hands of politicians and to an independent commission, which several other states have done or in the process of doing.

But that’s tricky in North Carolina. The state does not allow for statewide referendums, and the party in power at the General Assembly don’t seam eager to let go of that power.

“We have to separate the map making, taking it out of the lawmakers' hands and putting it into an independent entity like a citizens’ commission,” he said.

)