On Thursday morning, the North Carolina General Assembly will take up the criteria for redrawing the state’s political districts. And at 1 p.m., the U.S. Census Bureau plans to release the long-overdue population data so the state and local leaders can redraw the maps.

Each decade, the federal government does a complete census of the United States. The next year, states redraw the lines for congressional and legislative districts. Many local governments redraw their own political lines too. The population numbers normally come in early April, but delays from the coronavirus pandemic mean the data is months behind schedule.

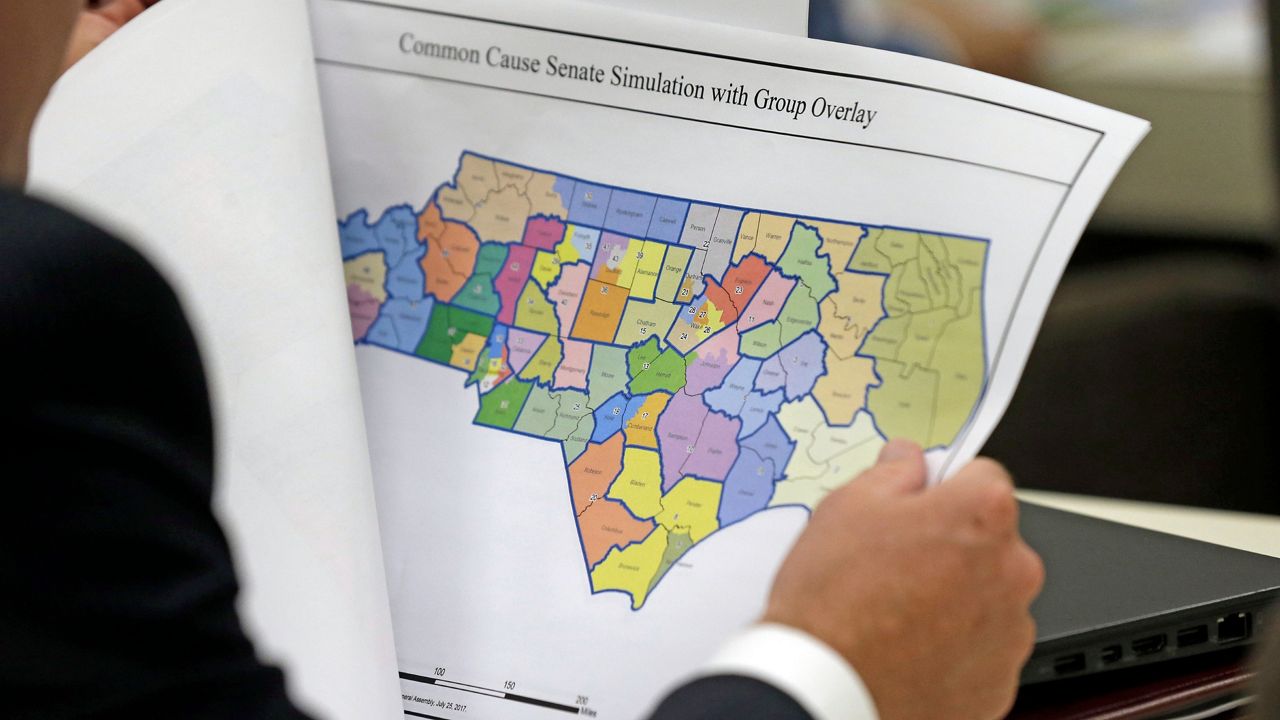

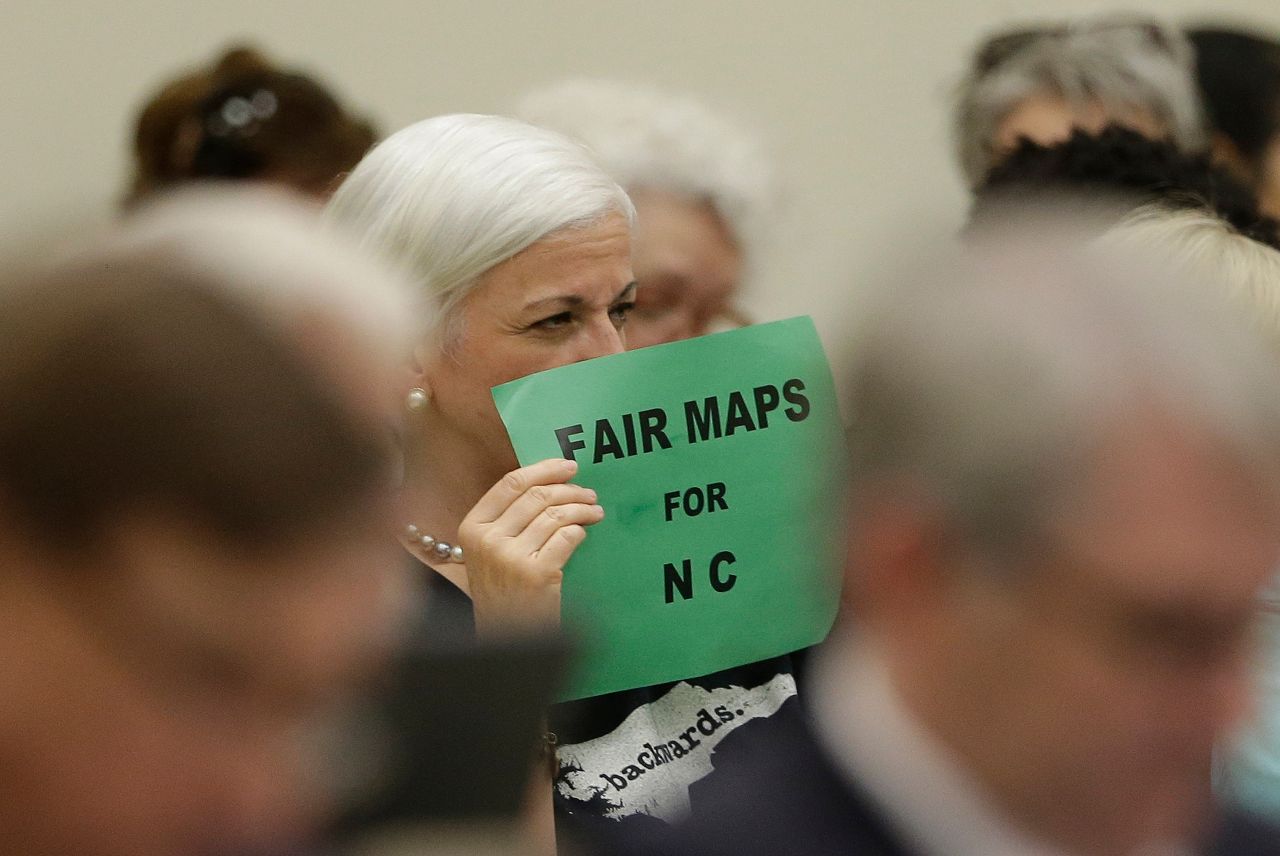

The last time North Carolina went through redistricting, the state became a national example of political shenanigans and gerrymandering. Lawsuits lasted for years and a judge threw out the maps in 2019.

Because of the census delays, the North Carolina General Assembly and local commissions and councils are working on a much tighter schedule to make new maps. Legislators in Raleigh are hoping to get the maps finalized and passed through the House and Senate by late November, before the Dec. 6 filing deadline for elections for Congress and the state legislature next year.

One of the biggest questions for map makers this year will be just how to fit another congressional district in North Carolina. Thanks to a growing population, North Carolina will get a new seat in the U.S. House of Representatives with a 14th Congressional District.

The census collects all sorts of demographic information each decade, but only a small slice of that data will be released Thursday. The data coming out will focus on what’s needed for redistricting: population change, race, ethnicity, voting-age population and housing occupancy status.

“The purpose is to ensure that voting power and representation are distributed equally,” said Kelly Tornow, a lawyer with the North Carolina State Board of Elections.

After the contentious map-making and lawsuits of the last decade, all eyes are on the Republican-controlled legislature as they get ready to make new maps.

Gerrymandering means “drawing districts in ways that produce different results that may not be proportionate to the electorate,” Tornow said Wednesday during a seminar for local officials around North Carolina.

Not all gerrymandering is against the law. Racial gerrymandering is illegal. “Political gerrymandering is OK, at least some degree of political gerrymandering,” she said.

“Sometimes is can be hard to determine whether there’s a racial gerrymander or a political gerrymander,” Tornow said. “This can occur when someone’s race is closely associated with someone’s party affiliation.”

The state or local governments could still face lawsuits over political gerrymandering. But, Tornow said, “It’s a higher bar to cross.”

Duke mathematician Jonathan Mattingly, who testified in court cases over gerrymandering in North Carolina, said drawing the maps can change who is in control of the state.

“There was a lot of uproar because there was an election where just over 50% of people voted for one party, and yet that party only got four of 13 seats. So the other party got nine. People immediately got upset about that and said that’s not democracy,” he said in an earlier interview with Spectrum News 1.

Draw North Carolina’s congressional map one way and one party could get nine seats and the other win four. Draw them another way and the results can flip completely.

“We talk a lot about stuffing ballot boxes or fraudulent voting or voter suppression, but no one has ever accounted for those swings you see just by who draws the maps.”“That’s saying that the will of the people is being drowned out by the will of the people who are drawing the maps,” Mattingly said. “We talk a lot about stuffing ballot boxes or fraudulent voting or voter suppression, but no one has ever accounted for those swings you see just by who draws the maps.”

Mattingly has made a mathematical model to detect gerrymandering in the maps. He said he’s planning to run his model against the maps coming out of the North Carolina General Assembly to see how they perform.

“If that map is way out of whack, for instance if you find districts that have way more Democrats in them or way more Republicans, then that means that somebody has put extra Democrats or Republicans in there, probably on purpose because it would have been difficult to do by accident,” Mattingly said. “That’s called ‘packing and cracking’ and that leads to diminished political voice.”

Making fair maps, Mattingly said, is about setting a certain set of principles to make the maps by and then sticking to those criteria.

On Thursday, as the country waits for the Census Bureau to release the new data, the North Carolina General Assembly will be finalizing the list of principals to guide the redistricting process.

The draft rules for drawing the maps mean lawmakers can’t consider race, partisan data or past election results. But they can consider where current elected officials live to keep them in the same districts.

Here’s the draft of what legislators in Raleigh are considering, as of Wednesday afternoon:

- Equal Population. The Committees will use the 2020 federal decennial census data as the sole basis of population for the establishment of districts in the 2021 Congressional, House and Senate plans. The number of persons in each legislative district shall be within plus or minus 5 percent of the ideal district population, as determined under the most recent federal decennial census. The number of persons in each congressional district shall be as nearly as equal as practicable, as determined under the most recent federal decennial census.

- Contiguity. Legislative and congressional districts shall be comprised of contiguous territory. Contiguity by water is sufficient.

- Counties, Groupings and Traversals. The Committees shall draw legislative districts within county groupings. Division of counties in the 2021 Congressional plan shall only be made for reasons of equalizing population and consideration of double bunking. If a county is of sufficient population size to contain an entire congressional district within the county’s boundaries, the Committees shall construct a district entirely within that county.

- Racial Data. Data identifying the race of individuals or voters shall not be used in the construction or consideration of districts in the 2021 Congressional, House and Senate plans.

- Voting districts. Voting districts should be split only when necessary.

- Compactness. The Committees shall make reasonable efforts to draw legislative districts in the 2021 Congressional, House and Senate plans that are compact.

- Municipal Boundaries. The Committees may consider municipal boundaries when drawing districts in the 2021 Congressional, House and Senate plans.

- Election Data. Partisan considerations and election results data shall not be used in the drawing of districts in the 2021 Congressional, House and Senate plans.

- Member Residence. Member residence may be considered in the formation of legislative and congressional districts.

- Community Consideration. So long as a plan complies with the foregoing criteria, local knowledge of the character of communities and connections between communities may be considered in the formation of legislative and congressional districts.

Once lawmakers draw up the new maps, they will have to go for a vote in the North Carolina House and Senate just like any other bill in the General Assembly. The main difference is, once they’re passed, the governor cannot veto the bill unless it has any unrelated provisions.

But, as North Carolina saw over the last decade, the maps can end up in court, leaving it to a judge to decide if they’re fair.