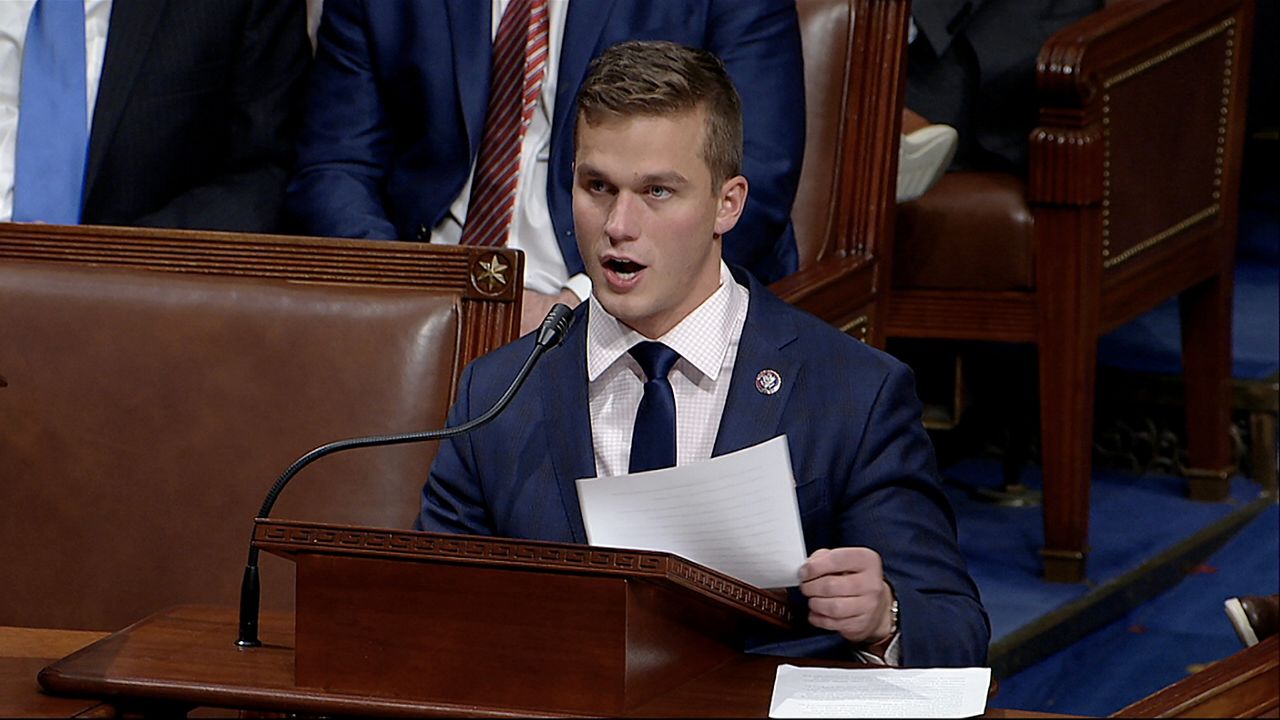

After just a month in Congress, North Carolina Rep. Madison Cawthorn has made a big splash on the national stage. He’s already been featured on national news networks and been the subject of stories in magazines like Time and Esquire.

Cawthorn was on the stage at the pro-Trump rally on January 6.

“This crowd’s got some fight in it,” he said a couple hours before members of that same crowd attacked the Capitol building.

At 25, Cawthorn is the youngest member of Congress. His politics and style are far-right with a firebrand in the mold of Donald Trump. Indeed, he emerged as a loyal Trump supporter as he ran to represent North Carolina’s 11th District in the western corner of the state.

Speaking to political scientists around North Carolina about Cawthorn’s rise, one thing is clear: Cawthorn has built his persona and, at least so far, bet his political career on Trump’s legacy. That puts him in the middle of a fight in the GOP about the future of the party, and it’s not clear how this will all work out for Cawthorn, or the people in North Carolina who elected him.

“I’ve never seen a freshman member of Congress get this much attention. I also can’t recall a member of Congress getting this much negative attention,” says Chris Cooper, a political science professor at Western Carolina University in Cawthorn’s district.

“Is all news good news? Will any of this negative coverage hurt him, or is he just getting what he wants, which is more coverage,” says Cooper, who is writing a book about the political history of the 11th District.

American Patriotism will never be silenced! Honored to speak out in defense of the Constitution! pic.twitter.com/bS05aU4XDb

— Madison Cawthorn (@CawthornforNC) January 6, 2021

With just barely weeks in office, Cawthorn has been accused of pushing Trump’s false narrative that the election was stolen and of lying about his acceptance into the Naval Academy. Before the election, a social media post surfaced of Cawthorn at Adolf Hitler’s summer home, saying the visit was on his “bucket list.”

When he won the election, Cawthorn tweeted, “Cry more, lib.” Now, he’s selling shirts with the same words (and facemasks with the word “useless” across them) while also calling for bipartisanship in Washington.

After the attack on the Capitol, Cawthorn voted in the House against certifying President Joe Biden’s election win. He faced calls for his resignation after that vote. Last week, The Charlotte Observer editorial board called Cawthorn an "embarassment."

“Typically, newly elected representatives don’t gain as much media attention unless they put themselves into the spotlight,” says Catawba College political science professor Michael Bitzer.

“There’s a classic line in studying Congress: members who get elected are either workhorses or show horses. The workhorses tend to be those that really buckle down, that do the necessary work to understand public policy. And then you’ve got the show horses that are simply in it for the limelight to gather attention,” Bitzer said this week. “Right now, it feels like the representative from the 11th is much more of a show horse.”

But more than being a show horse, Cawthorn, and some other freshman members of Congress like Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia, show a split in the GOP.

Cry more, lib.

— Madison Cawthorn (@CawthornforNC) November 4, 2020

“This shows the intra-party dynamics within the Republican Party on full-display. Cawthorn is very much an ally of Trump,” Cooper says.

“The media and many people like to think about the party dividing clearly along ‘reject Trump’ versus ‘keep the Trump legacy alive’ wings of the party. If that is really the way the party is splitting, it’s obvious that Cawthorn is on the Trump side of that,” N.C. State University political science professor Andrew Taylor says.

Taylor said Cawthorn’s newfound fame comes down to one thing: “He makes good TV.”

In a recent story, Time said it received a copy of an email Cawthorn sent to another Republican.

“I have built my staff around comms rather than legislation,” the email read, according to the magazine.

All of this attention brings up questions about what this means for North Carolina’s 11th Congressional District.

“For a lot of members, it’s all about, ‘What can i do for the district that will get me re-elected?’ What we’re seeing nowadays is, ‘What can I do nationally?’ and sometimes the local dynamics get put in the back seat,” Bitzer says.

Charlotte Observer Ed Board: Madison Cawthorn is a North Carolina embarrassment.

— Kyle Griffin (@kylegriffin1) January 31, 2021

"Can someone please keep Madison Cawthorn away from ... the microphones? And really, most situations in which he publicly tries to turn words into meaningful thoughts?"⁰https://t.co/UMZrCa1K4F

Taylor says it would be hard for any new Congress member to have much impact. “They’ve elected a junior member of the minority party. I don’t see Cawthorn having any real substantive influence in the House of Representatives.”

But it’s hard to know what all the attention Cawthorn is getting could mean in the long-term, Taylor says.

“I don’t think it makes him a player in the House of Representatives anytime soon. In fact, if anything, it might hurt him. He’s just going to become a little bit like a freak show, sort of exotic, interesting but not influential player,” he says.

In a statement, Cawthorn Spokesman Micah Bock said, “Rep. Cawthorn is working diligently in Washington to represent the people of NC-11 and no one else. National attention from the media, while helpful in shedding light on issues important to the people of Western North Carolina, does not distract him from his goal of serving constituents.”

I am fighting for the mountain values of North Carolina; battling career politicians and a Washington machine that places partisanship over people.

— Rep. Madison Cawthorn (@RepCawthorn) January 20, 2021

Let’s see if the Biden Administration is willing to do the same.

Read my challenge to the incoming President-elect below: pic.twitter.com/Qcc7YVB6At

There are already murmurs about a primary challenge for Cawthorn in 2022, says Cooper, who lives in the 11th District.

Cawthorn is the pro-Trump candidate in the western North Carolina district. But with more than a year to go until the next primary election, it’s hard to tell what the political landscape could look like.

All this national attention could help Cawthorn a lot with fundraising, but it could also bring challenges from other, more establishment Republican candidates.

If you'd like to announce that you are "useless," Freshman Congressman Madison Cawthorn's campaign website has the product for you! pic.twitter.com/Xb74M3xEYi

— DJ Judd (@DJJudd) January 28, 2021

“This could help him because he will be the clear Trump protege. If Trump’s really popular at the time, it will help him win a primary. If not, this is going to hurt him and he will draw primary challengers and may lose a primary,” Taylor says.

“There are already rumors that he might be primaried from the right, which is pretty extraordinary for his first month in office,” Cooper says.

Bitzer, for his part, says the past couple of years in politics have thrown everything up in the air.

“We as political scientists know what has happened in the past. I’m not sure we can necessarily look to the past right now and say, with any kind of assuredness, this is what’s going to happen in 2022,” he says.