WILMINGTON, N.C. — The start of the school year was marked by shootings in two North Carolina schools, the first in Wilmington, and then in Winston-Salem. Advocates say gangs and youth gun violence never went away during the pandemic, but it’s getting more attention as it spills onto school campuses.

This week, police in Charlotte arrested a 15-year-old and a 19-year-old for allegedly being involved in a gun battle between cars where another 15-year-old and a baby were injured.

Schools are on edge. Threats on social media about violence at North Carolina schools has sent classrooms into lockdown, including several Wake County schools on Wednesday.

In Wilmington, where a shooting at New Hanover High School injured a student three weeks ago, city and community leaders are wrestling with what to do next.

“No one is framing this as a ‘school safety problem,’ in and of itself,” County Manager Chris Coudriet told the New Hanover County Board of Commissioners this week. He said it’s a “symptom of a larger community problem.”

The people working on the ground in Wilmington’s underserved communities agree with him.

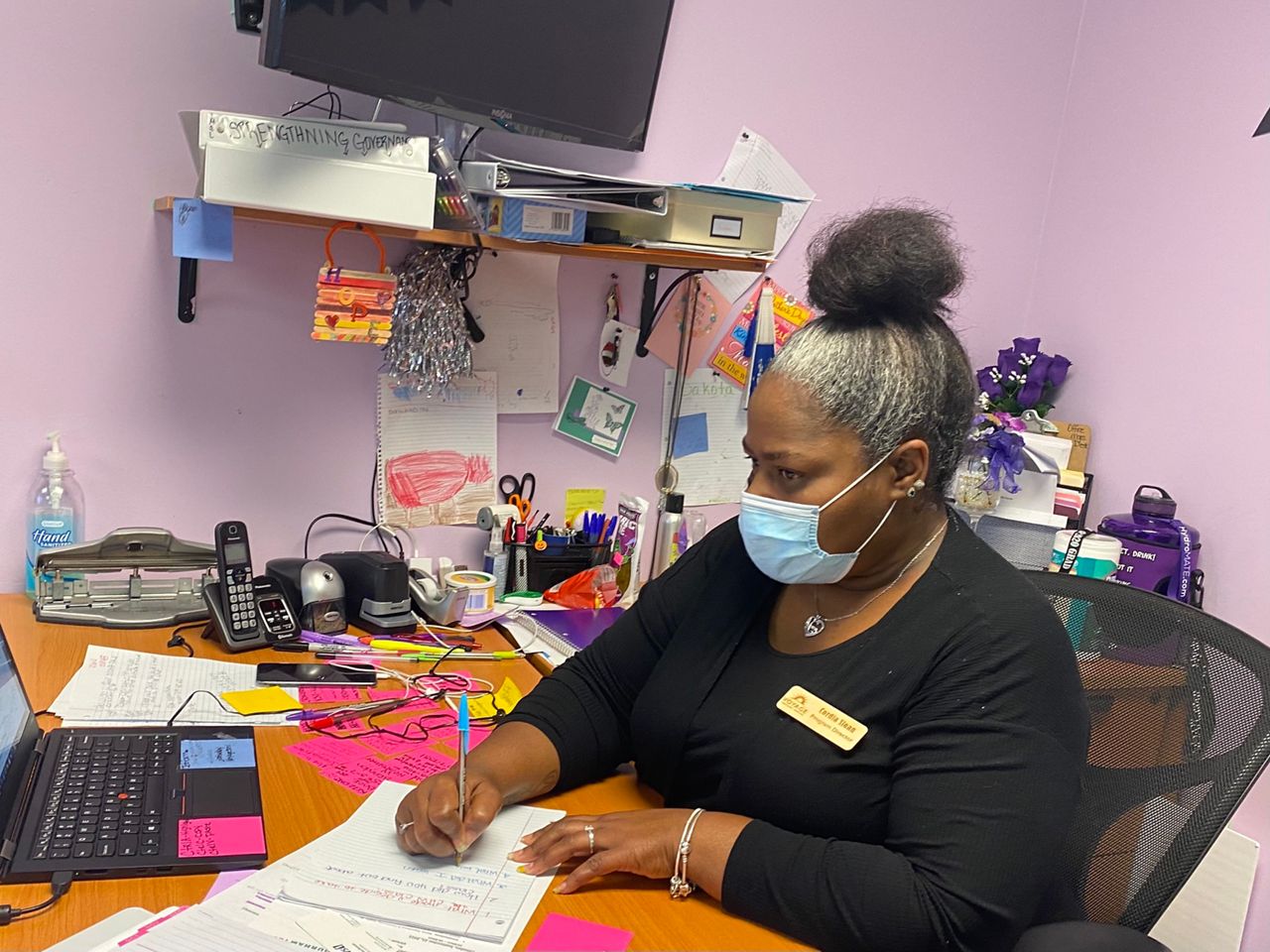

“We hear all these people talking but nobody is in the street trying to get these children here, trying to talk to children on the streets,” said Cordia Sloan, program director for the nonprofit Voyage Wilmington. “What can we do? Our babies are dying. There’s no way a mother should have to bury their child.”

The county plans to tap into a $350-million rainy day fund to improve school safety. Coudriet said the county is working with school administrators, law enforcement, teachers and experts on school facilities and mental health to look at hard improvements to schools.

On Wednesday, two sheriff’s office cars and a Wilmington police car were parked outside New Hanover High, where a fight turned into a shooting on Aug. 30 that injured one and ended with a 15-year-old facing attempted murder charges.

Coudriet said the school system has done security audits to look at how safe New Hanover County schools are. “We haven’t applied the appropriate numbers of resources,” he said.

“These are the things that we can do on the perimeter of schools and work our way inside,” Coudriet told the Board of Commissioners. But things like metal detectors and fencing only move the problems just off campus, he said.

“You can have all the clear bookbags in the world in these schools, that’s not going to stop a child from getting a gun if they want one. You have to start a foundation. We have to be able to get these kids able to trust the system again, because they don’t,” Sloan said, sitting in Voyager’s small cinderblock building in north Wilmington.

“In addition to school safety, we must also talk about this from a community-wide perspective in the context of community violence,” Coudriet said in a statement Wednesday. “This community-based work is not as near-term as school safety and supports within schools. It is a much bigger, future-focused discussion that must start small and evolve with an intentional and comprehensive plan. We may not see immediate change, but I believe it is going to create lasting change.”

That’s where Sloan and programs like Voyage Wilmington come in. Voyage started in 2008 as The Blue Ribbon Commission on the Prevention of Youth Violence, part of the United Way of the Cape Fear Area.

Voyage Executive Director Genna Wirth said the organization has been working to get to the root causes of youth violence in Wilmington.

Their goal is to “create healthier, more successful communities from the bottom up,” Wirth said. “We can’t empower these kids without empowering their communities.”

The nonprofit runs programs for youth employment, partnering with companies and local government to get kids summer jobs and teach them financial literacy, resume building and job skills. They also offer things like free tutoring, afterschool programs and community events.

Sloan works everyday trying to get to those root causes and empower her community to keep children out of gangs.

“You can have five kids, all being taught and raised in the same home, but three out of those five are going to hit the streets. This I know, because of my children. You know, you weren’t raised like that, but the street is so overbearing,” Sloan said.

“The kids just think, maybe this is what I’m supposed to be doing, versus what mom says, because ‘look at mom, she’s struggling,’” Sloan said. “It’s stemming, I’m feeling, from gangs. What is it the kids are seeing that’s exciting? What’s so exciting about being in a gang? Because you get to kill somebody. But then, the harsh reality is, once you start this gun thing, you won’t be able to come home.”

Schools across North Carolina, in cities from Charlotte to Winston-Salem to Wilmington, have been adding more officers in school buildings and looking at other immediate measures to keep students safe.

Nonprofits like Voyage in Wilmington are also continuing their work across the state to try to tackle the structural issues that can lead kids to gangs and gun violence.

“The longer we sit back and just talk and talk and talk, the worse things are getting,” Sloan said. It will be up to governments and groups like hers to continue supporting kids and their communities to stop this kind of violence in the long term.