As of Wednesday, county boards of elections have sent out more than 91,000 absentee ballots for the Nov. 8 election, according to state data. More than half of those are for Democratic voters, another third is for unaffiliated voters and the rest are for Republicans and third parties. In the last midterm, in 2018, about 70,000 people cast mail-in ballots, state data shows.

“You can definitely tell there’s a lot of interest in this election,” Watauga County Elections Director Matthew Snyder said. But county election offices in North Carolina are also working through a backlog of public records requests looking for election data and getting ready for possible issues with poll observers and people questioning election integrity this year.

The records requests include asking for policies, procedures and result tapes from vote tabulators. Some have come from local voters and others from national organizations, said Charlie Collicutt, director for the Guilford County Board of Elections. Some of the records requests he's denied because they include confidential information that could identify voters.

“We’ve seen more activity around that than last midterm, but it seems like a continuation from 2020 when we were getting a lot of records requests,” he said.

County election directors around the state say they have been getting a lot more records requests than before the 2020 election, when then-President Donald Trump tried to cast doubt on the election results showing he lost his bid for reelection. Trump’s efforts to discredit the election results were roundly rejected by the courts, but ultimately led to the deadly Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol.

The midterms are the first big election since 2020. The New York Times recently reported North Carolina Republican Senate candidate Rep. Ted Budd wouldn’t commit to accepting the results of the midterm election in his race against Democrat Cheri Beasley. He later walked back those comments.

In a series of interviews with elections officials around the state, many are still concerned about mistrust in elections.

“The poll observers are there to observe, the law says they can observe. But then, what is that? And when you’re talking about something that has some gray area, it’s kind of subjective, what do some people feel is observation and what do some people feel is too much intrusion,” Collicutt said.

“With that kind of gray area, it can lead to issues,” he said. “Sometimes they're specific to those two people, sometimes they’re a larger illustration of how that can be interpreted.”

In Brunswick County, Elections Director Sara LaVere said she saw a big uptick in the number of election observers for the primary earlier this year.

“Some observers questioned procedures,” she said. But LaVere said she has a good relationship with the two big political parties in the county, and they did not have any major issues with observers.

The three elections directors, from Watauga, Guilford and Brunswick counties, say they have not had any major issues with poll observers or others in the community questioning election results.

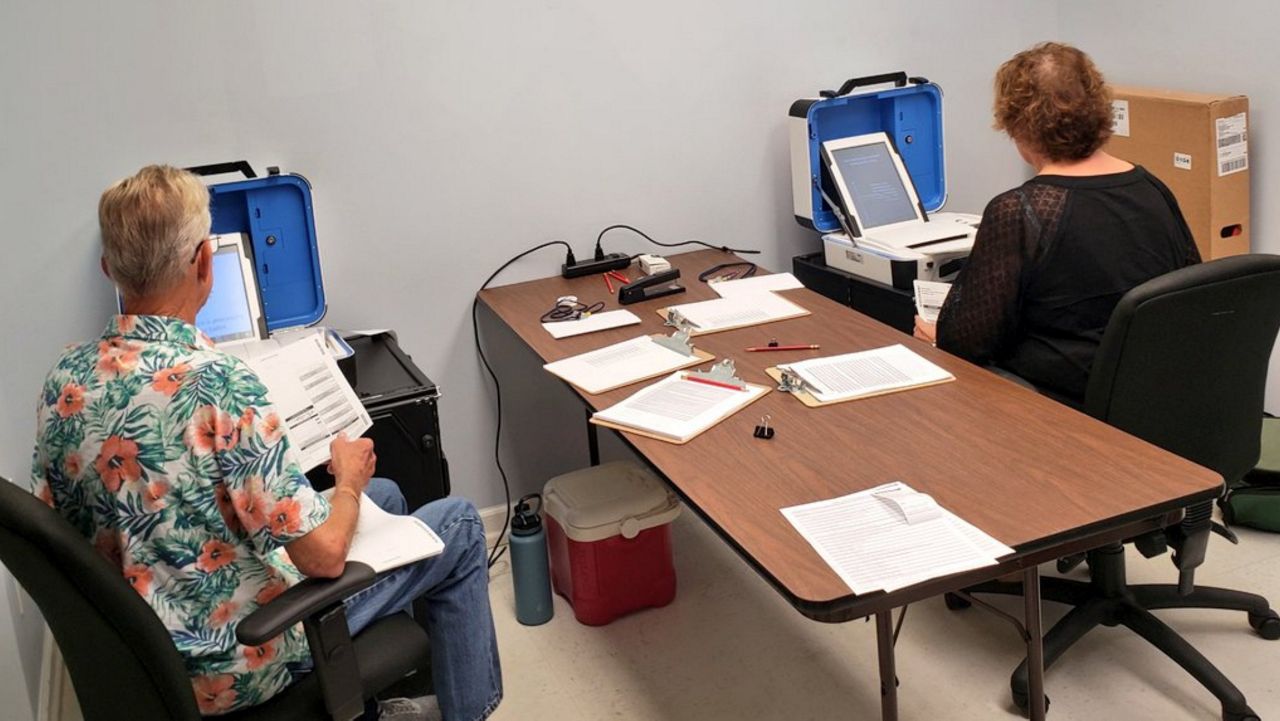

LaVere said she’s been working to make the elections process as transparent as possible, even live streaming from the room as they go through logic and accuracy testing on the county’s voting equipment.

The North Carolina State Board of Elections recently tried to put in new rules to clarify what partisan poll observers are and are not allowed to do. Those rules, passed unanimously by the bipartisan board, were rejected by the state Rules Review Commission, which is appointed by the Republican-led General Assembly.

“These rules were designed to go into place during the midterms because we do have concerns that poll disruption is the aim of a very small fraction of our society, but something that we need to be concerned about,” said Damon Circosta, chair of the State Board of Elections.

“We need to make sure our observers know what they can and cannot do,” Circosta said. “Observers are there to observe, not to disrupt, and voters are there to vote. Our precinct officials are there to make sure the rules are being followed.”

Circosta said he disagreed with the commission’s decision to reject the new rules.

“I don’t believe the RRC will be the last word on how this all goes down,” he said, adding that the board could try a different procedure to make new rules or take the matter to the courts.

Another question already in the courts is the due date for mail-in ballots, which the State Board of Elections wants to delay by a day. The due date for mail-in ballots under the current law falls on Nov. 11, that’s Veterans’ Day, a federal holiday.

These kinds of questions of voting administration would not typically come to the point of lawsuits, said Asher Hildebrand, a public policy professor at Duke University.

“It hasn’t traditionally been a partisan issue, how we treat these wonky questions of election administration. But in today’s environment, in the wake of ‘the big lie,’ everything becomes a partisan issue, even if it's these fairly mundane proposed changes to administration,” he said.

“It’s a great example of just how politicized these kinds of narrow questions of election administration have become,” Hildebrand said. “The fact that the battle lines were drawn around when a ballot that has been legally requested by a legal voter and legally submitted and returned, just when the envelope arrives: it shouldn’t matter but it does.”

While Circosta and the State Board of Elections are in Raleigh trying to figure those questions out, county election officials around the state are working on the logistics to make sure the next election goes off smoothly.

“Right now, for us in Guilford County it’s ballots. How many ballots do we need? Where do they go? What kind of logistics do we need? How many trucks, how many personnel? And the testing of those ballots,” Collicutt said.

They’re also working on the time-consuming, but equally important work, of making sure people have faith in elections.

“I’m very happy a lot of people around the country are starting to look at how their elections are conducted and how they happen and the rules involved, I think that’s wonderful for all of us in the long run,” said Snyder, the Watauga County elections director.

“We take elections very seriously,” he said. “I come from generations of military veterans. I owe it to them, I owe it to the public, and I owe it to the country to make sure we’re doing things the right way and I’m not going to let anybody compromise that.”

He said all this extra work responding to public records requests and talking to people in the community is not without its challenges.

“When we’re busy in the midst trying to get everything ready and prepped for the election, it does put a strain on our resources,” Snyder said. “We don’t have big staffs, we weren’t really built for the attention we are getting.”

“They need to communicate with and reassure the public that elections are secure, that they are being conducted with integrity, and that ultimately people can trust the results. And that’s a huge challenge, a huge burden to place on the backs of a workforce that has limited resources, is largely volunteer-based,” said Duke’s Hidebrand.

Snyder said they are trying to give the records requests and all the questions the time they deserve.

“We get it. People have questions. It’s on the news a lot and people have questions locally and so we understand,” he said. “It’s their right to know how elections are conducted and it’s our obligation to inform them of that.”