A trial over whether North Carolina’s new political maps are constitutional wrapped up with closing arguments Thursday. The three-judge panel has until Tuesday to issue a ruling.

The cases will likely end up before the North Carolina Supreme Court no matter how the trial court rules. The Supreme Court ordered a tight timeline for the lawsuits to move forward so it could potentially be able to issue a final ruling with enough time before the 2022 primary elections.

The lawsuits are over redistricting and whether the maps are unconstitutional gerrymandering, disenfranchising left-leaning voters and Black voters.

Redistricting, the process of drawing political districts, comes every 10 years after new census population counts. The process in North Carolina was done on a tight deadline last year because of COVID-related delays getting population counts from the U.S. Census Bureau.

In North Carolina, redistricting is a political process done by members of the General Assembly. During the last redistricting round, the maps were the subject of political and legal fights for most of the decade, and courts sent legislators back to the drawing board several times.

The N.C. Supreme Court last month ordered the primary elections be delayed from March until May so the lawsuits challenging the maps could be heard.

The state Supreme Court combined two lawsuits that accuse the Republican-led legislature of extreme and unconstitutional gerrymandering.

One lawsuit argues the new maps disenfranchise Black voters and dilute their political power. A second says the maps divide Democratic and left-leaning voters to create more safe seats for Republican candidates.

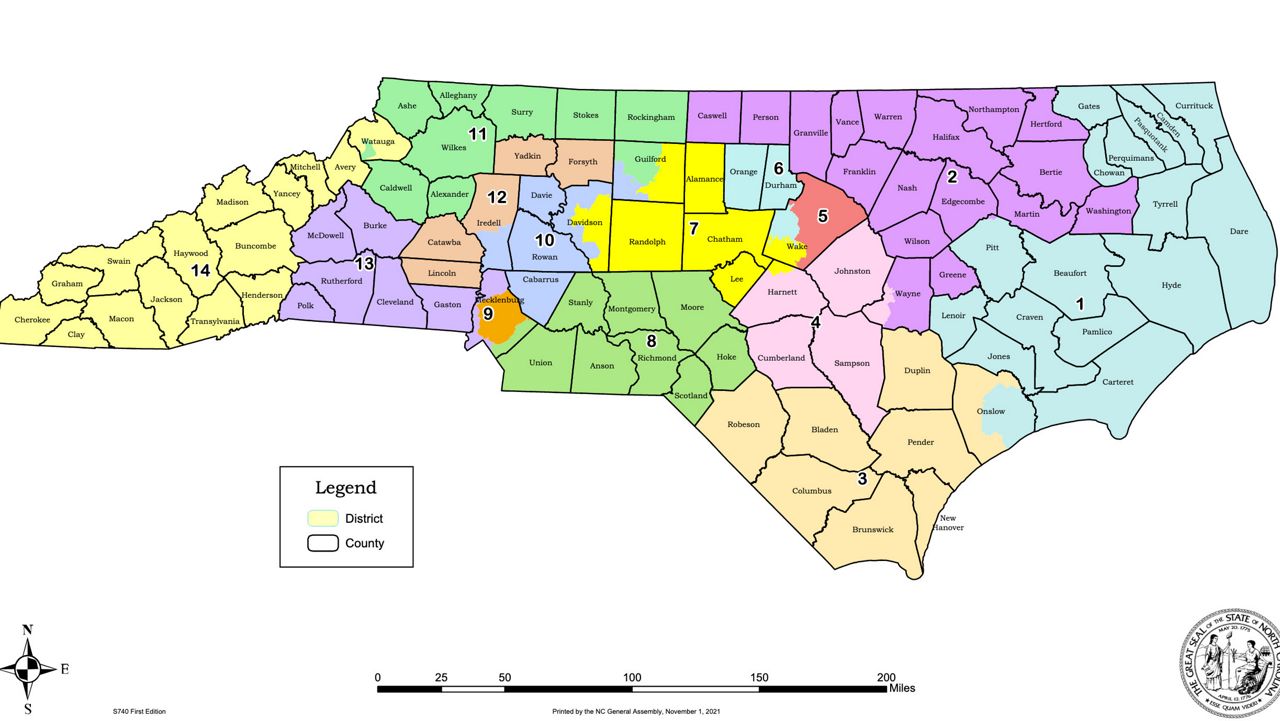

At issue are the congressional maps, which could impact the balance of power in the U.S. House of Representatives. The lawsuits also challenge the maps for the N.C. House and Senate, which could potentially lead to a Republican supermajority that could overrule the governor’s veto.

The lawsuits were filed late last year by Common Cause North Carolina and the North Carolina League of Conservation Voters.

Gerrymandering is drawing the electoral maps in a way to give one political party or race an advantage in elections. It’s done by either packing certain voters into a district so their votes all go to one seat or by breaking them up into several districts to dilute their voting power.

Nonpartisan groups like the Princeton Gerrymandering Project said all three maps, for Congress and the state House and Senate, gave Republicans a significant advantage in elections.

Currently, Republicans hold eight of North Carolina’s congressional seats and Democrats have five.

North Carolina this year added a new seat in the House because of population increases. But with the new maps, Republicans would likely win at least 10 seats and Democrats would have four.

In statewide elections, North Carolina is typically split down the middle between Republican and Democratic voters.

The plaintiffs in the case brought in political scientists and mathematicians to testify and show the maps are illegally gerrymandered.

Duke University’s Jonathan Mattingly, a mathematician, told the court that his team used computer models to make 100,000 maps for both the state House and Senate. Those nonpartisan maps indicated that the maps made by the legislature showed a systematic bias for Republican candidates.

The plaintiffs in the trial looked particularly at urban areas with concentrations of Democratic voters that were broken up in the new maps and combined with more Republican-leaning areas.

Whether or not the maps are unconstitutional is up to the three-judge panel hearing the case. And then the final decision will likely rest with the N.C. Supreme Court.

One of the big questions the judges will have to face is whether the courts can even have a say in the drawing of the maps.

Almost two decades ago, in another round of legal wrangling over redistricting, the N.C. Supreme Court decided that the General Assembly can consider political advantage in drawing new maps.

More recently, in 2019, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that partisan gerrymandering is not an issue to be decided by the federal courts, leaving it up to state courts and legislators. That ruling came in another case about gerrymandering in North Carolina.

The GOP-led redistricting committees in the General Assembly called the 2021 process the “most transparent” in North Carolina’s sordid history of redistricting. Typically, under both Republicans and Democrats, the maps have been drawn behind closed doors with partisan consultants.

Last year, Republican leaders on the committee said the maps would be drawn in open committee rooms, with live streams online from the rooms and the map-making terminals. They said the committees would only consider maps drawn in the public rooms.

During the third day of the trial, Rep. Destin Hall, who chaired the House Redistricting Committee, revealed that he looked at “concept maps” that were drawn by someone outside the committee room. Hall first mentioned these outside maps in a deposition given last month.

It’s not clear what impact those other maps had on the process. Hall said they had been lost or destroyed in the two months since the maps were completed.

Hall and the other leaders on the redistricting committees said they did not consider partisan or racial data when building the new maps, a change from years previous. Some argue that the state violated the Voting Rights Act by not including racial data.

The trial concluded Thursday. The three-judge panel has until Tuesday to issue a written ruling, a fast timeline for such a complex case. No matter how the judges rule, the cases will likely be appealed. The case will skip the usual next step of going to the state Court of Appeals and go straight to the N.C. Supreme Court for a final ruling.

If the Supreme Court finds the maps are constitutional, the 2022 elections can go ahead with the current maps. But if the justices rule that the maps are illegal, they could send the legislature back to the drawing board to produce new maps before the primary elections in May.