CAPE HATTERAS NATIONAL SEASHORE, N.C. — Driving south out of Nags Head down the Outer Banks along Highway 12, the barrier islands are narrow. Sand dunes pile up to one side of the two-lane road, the marsh on the other.

When the wind picks up, the sand starts to creep into the road. Tropical storms, hurricanes and nor’easters, a part of life on the Outer Banks, regularly push the waves and sand right over into the sound, cutting off the towns from the mainland.

Jeff Ryder is the North Carolina Department of Transportation maintenance engineer for this part of the coast. A big part of his job is to keep N.C. 12 open.

“N.C. 12 is the only option for people to get to and from, to get to their stores, their doctor’s appointments, whatever. It is the one link, the only link, to Hatteras and the ferry systems to Ocracoke,” Ryder said.

“That’s why it’s very important to us to try and keep it as open and clear as possible at all times. Of course, Mother Nature has a different take on that, but we try and fight back as best we can,” he said.

Ryder has a team of about 15 people working year-round doing constant maintenance on the road to keep back the sand. When a big storm comes through, they can bring in help and equipment from the DOT and contractors to get the road back open.

“I have some employees who say they’ve moved the same grains of sand about a million times,” he told Spectrum News 1. Those employees work in some of the harshest conditions imaginable on this thin stretch of land out in the Atlantic.

“It’s not rocket science. It’s using bulldozers, excavators, front-end loaders, graders. Sometimes we have to reposition sand to other dunes, so we use dump trucks. But the cleanup after a storm can involve all kinds of things,” Ryder said.

“That roadway has been destroyed and rebuilt so many times, I don’t think we’re even on the right of way anymore,” he said.

The road started washing out so much, the state decided to build a bridge around the worst spots. The new $145-million bridge, called the “jug handle bridge” because of its shape, comes out of Rodanthe and cuts around some of the worst spots for the road, joining back up with the island a couple of miles north where it widens out again.

The 2.4 mile bridge is set to open later this year. After that, the DOT plans to remove the road from that stretch, part of National Park property called the Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge.

Ryder said he hasn’t seen storms get any worse in his decade as maintenance engineer for this stretch of the Outer Banks. But what’s making things harder for his crews is erosion.

“There’s very little beach left in that area,” he said. “The dunes look high, but if you walk on the back side, there’s no beach there and the water is usually lapping up against the back side of the dune.”

This probably won’t be the last big bridge project for the Outer Banks, said Rick Luettich, director of the University of North Carolina’s Institute for Marine Sciences.

North Carolina barrier islands, the lowest parts of them, become harder and harder to maintain and we may end up having to give back parts of them“I think that over the course of time we’ll see the North Carolina barrier islands, the lowest parts of them, become harder and harder to maintain and we may end up having to give back parts of them,” he said.

The biggest tool Outer Banks communities have to combat erosion from sea level rise is what’s called beach renourishment, essentially dredging sand from the ocean floor and pumping it back onto the beaches.

“We work really hard to put the coastline back the way it has been. So for roughly the last 50 or so years we’ve been trying hard with bulldozers and dump trucks and dredges and all of those things to hold the coastline in its place,” Luettich said. But that is just a temporary fix to buy time, he said.

The rate of sea level rise along this part of the Outer Banks is about 5.3 millimeters a year, based on measurements from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s tide gauge in Oregon Inlet that’s been taking measurements since 1977.

Researchers agree that the rate of sea-level rise will increase in the decades to come, but just how much is still an open question.

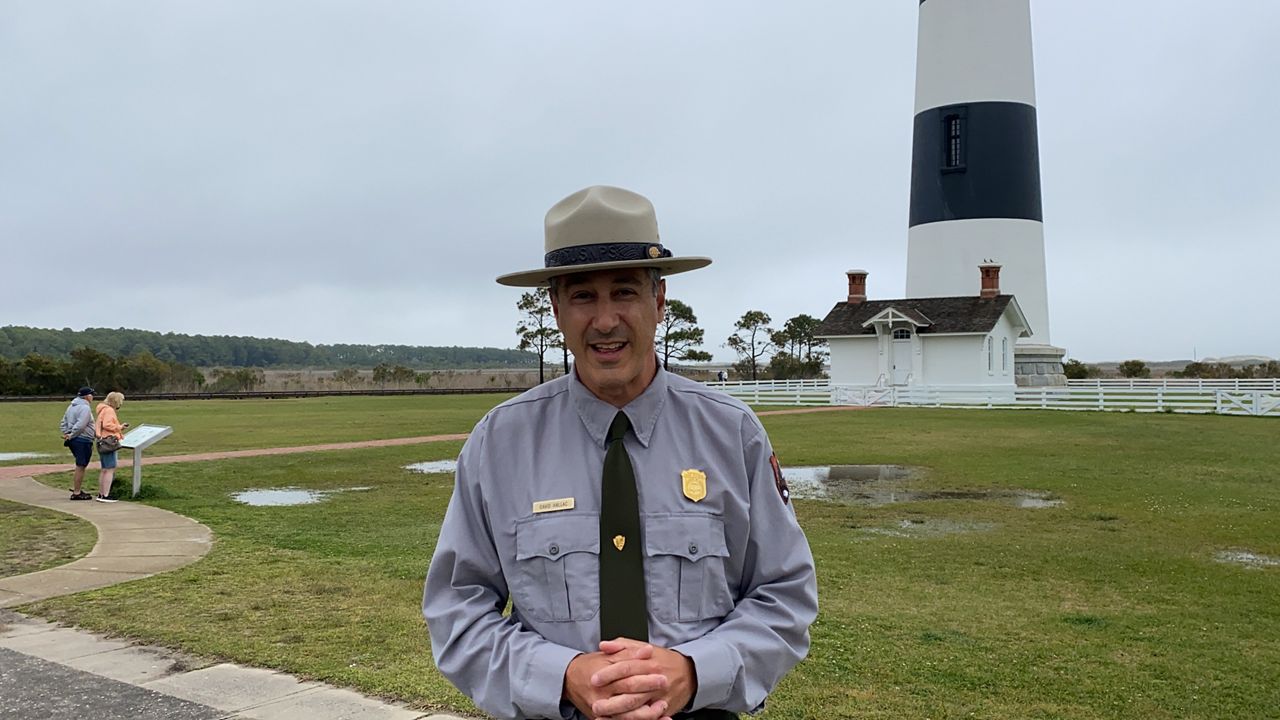

“This is Ground Zero,” said David Hallac, superintendent of National Parks of Eastern North Carolina, including Cape Hatteras National Seashore.

“Over the coming decades, we are looking at significantly more sea level rise and that will make life even more challenging,” he said, standing in front of the Bodie Island Lighthouse, a landmark on the Outer Banks.

Rising sea levels mean there could potentially be less habitat for birds and sea turtles. And for humans, the National Park Service could have to make changes to low lying parking areas and buildings, even the NPS’s own administrative offices.

“It’s not something that is going to happen to us, it’s something that is happening now and that ignoring the problem probably won’t make any progress for us,” Hallac said.

“It’s really important that we embrace the change, that we do our best to pay attention to the forecasts coming from NOAA and other scientists, and do our best to prepare now,” he said.

Projections from NOAA and other researchers give a big range for how much the ocean could rise in the coming decades, anywhere from a foot on the optimistic side to more than eight feet in extreme scenarios. Just how much depends on how the world addresses global climate change.

Three feet of sea level rise on the North Carolina coast would cover about 1,700 square miles of coast line with water, according to modeling by Climate Central, using data from NOAA and the U.S. Census Bureau. That includes almost 40,000 homes and $5.7 billion in property.

Modeling for sea level rise is difficult. Many researchers, including Climate Central, use what they call the “bathtub model,” which applies sea level rise to elevations on the existing coastline. But coastal areas are more complicated than that.

“The idea that we will see a meter of sea-level rise by 2100? Sure, we should plan on it. The question is, when do we get to that meter? When do we get to that half meter?” said Reide Corbett, director of East Carolina University’s Coastal Studies Institute on Roanoke Island.

“Scientists still have questions about what that projection looks like in the next 20 to 50 years,” he said.

Barrier islands and beaches move, estuaries and marshes can grow and big storms can reshape the landscape. So measuring what three feet of global sea level rise means for each coastal community is more complicated than comparing water level to the elevation of a house or a school.

what we’re seeing today is something we haven’t experienced in tens of thousands of years“Sea level has changed over time, but what we’re seeing today is something we haven’t experienced in tens of thousands of years,” Corbett said, and that is something that coastal communities have to prepare for.

Click for Rising Oceans Part 1: Sea-level rise is already reshaping North Carolina’s coast

Click for Rising Oceans Part 3: What are N.C. coastal communities doing to prepare for sea-level rise?

)