CHARLOTTE, N.C. — Time is no match for the memories that come flooding back for Bill Cathcart when he visits the Carroll (Rosenwald) School in Rock Hill.

He went to elementary school at the once all-African American school.

He remembers playing baseball on the field outside and thinking about the future.

“Fantasizing, imagining one day I would play for the Brooklyn Dodgers,” says Cathcart, who's also known as “Wallie."

Baseball, America's pastime, was also a sport divided.

While Cathcart didn't make it to the Brooklyn Dodgers he did play in the Negro Leagues.

The Negro National League started in 1920 when what was known as a gentleman's agreement between owners left Black players out of the major leagues and on their own.

“A lot of these players traveled throughout the Southeast, and so they weren't allowed to buy something to eat in the restaurants. They weren't allowed to stay in the hotels,” says Michael Turner Webb, who has become a historian of the Negro Leagues.

The pay was a fraction of what white players made. But what they did have was talent.

“The play was top notch and a lot better,” Webb says.

Players like Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell, and Buck Leonard emerged.

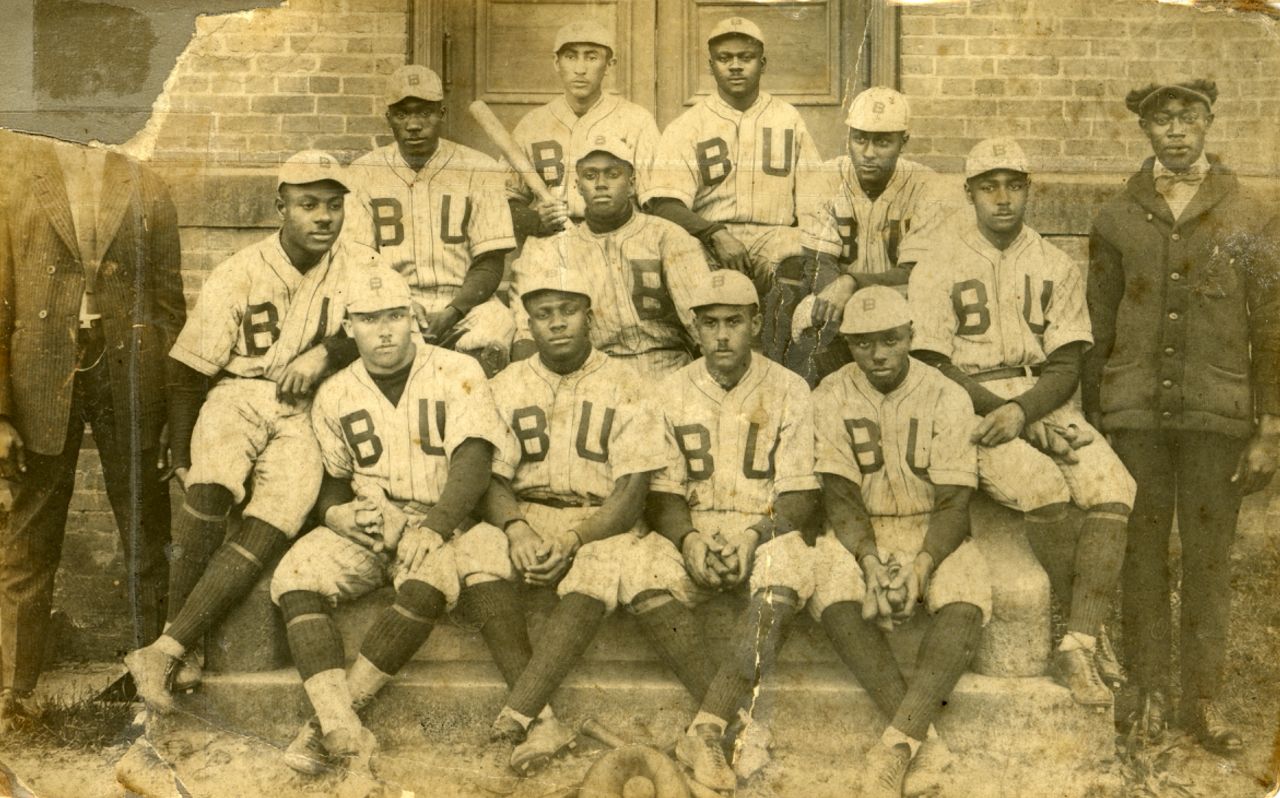

The teams, which mainly played in the Northeast, were fed some players from smaller teams in the South.

“You had baseball teams all across the Carolinas, in these local rural communities,” Webb says.

Such teams were the Charlotte Quick Steps, Black Hornets, and Red Sox. Webb says the Charlotte-area teams played at Johnson C. Smith University and the former Griffith Park.

“Wherever they could find a ballpark to play. They would play,” Webb says.

The dream was to make it to the top.

Cathcart was a pitcher for the Joe Black All Stars at the tail end of what was left of the Negro Leagues from 1959 to 1960.

“It wasn't my dream to be in the Negro League, my thing was to be in the Major Leagues to get the recognition...in some respects it wasn't considered professional baseball,” Cathcart says.

That eventually changed, but it took a century.

In December the MLB reclassified the Negro League as a major league.

“Finally,” Cathcart says. “Far overdue. Far overdue.”

An overdue history lesson righting a wrong for a time when the players were as good as ever, and the sport failed to keep up.