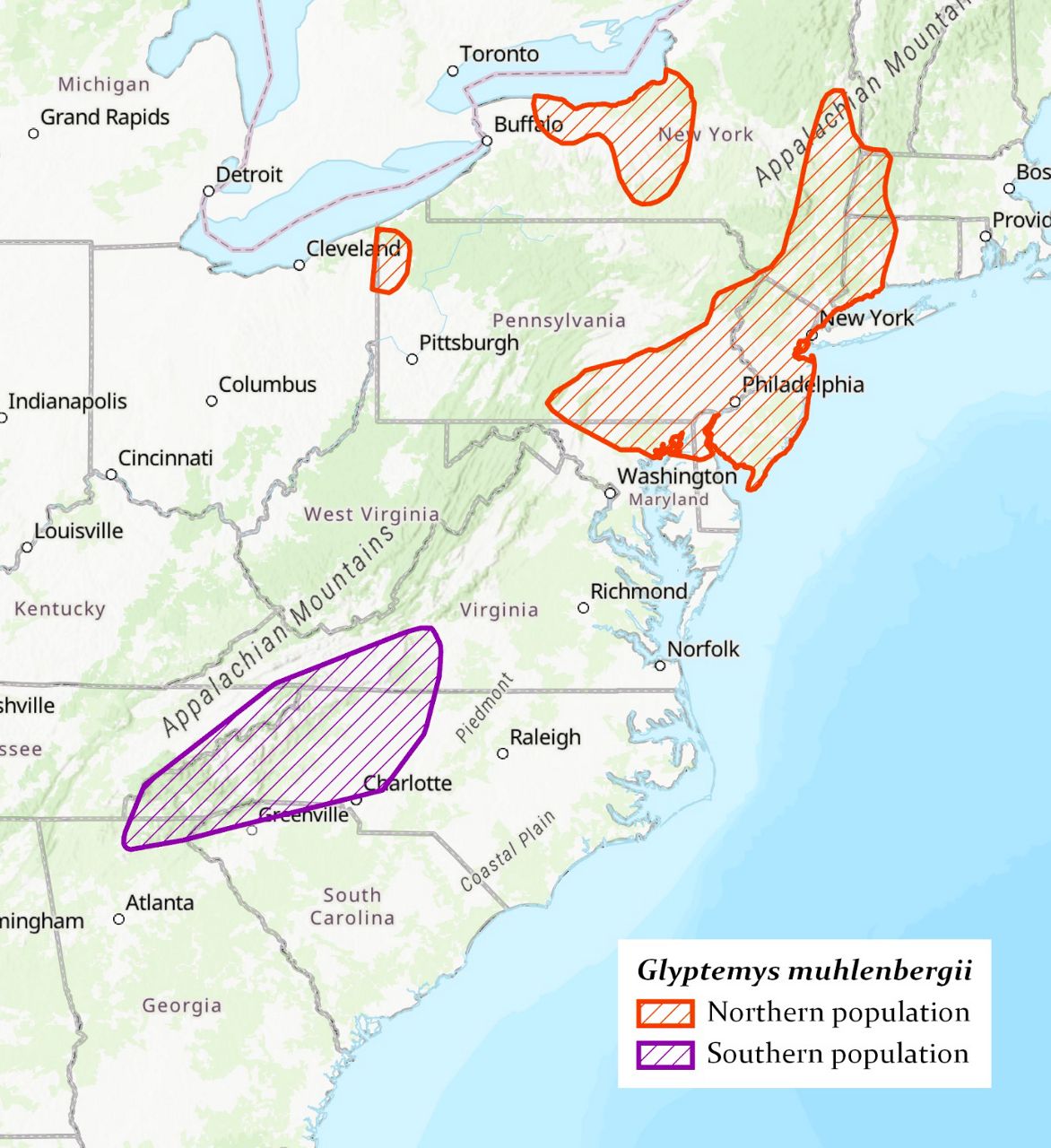

It’s the smallest turtle in North America. Its native range is mostly in western North Carolina, with some spillover into the surrounding states. The turtles have a distinctive yellow or orange patch on each side of the head. They live in mountain bogs, a distinct part of the southern Appalachian Mountains that’s been steadily disappearing due to development and environmental changes.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is considering listing the southern bog turtle as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act. A close relative, the northern bog turtle, was listed as a threatened species in 1997. That gave some protection to their southern cousins because of how similar they look.

“The bog turtle is North America’s smallest and rarest turtle species—and its most imperiled,” the Center for Biological Diversity said in its application to get the turtle listed as threatened or endangered.

“The southern bog turtle population has collapsed. Only 14 viable sites containing fewer than 2,000 individuals remain. Nearly all of its remaining sites are in serious decline,” the group said.

The center is asking the Interior Department to list the turtle under the Endangered Species Act and designate the remaining mountain bogs as “critical habitat” to protect them from development.

Most of the turtle’s habitat is in North Carolina, but it extends into small parts of Virginia, Tennessee, South Carolina and Georgia.

“Southern Appalachian wetlands are one of the rarest and most endangered ecosystems in the country,” the group said. In the turtle’s native range there was once more than 5,000 acres of mountain bogs, the center said. Now there’s less than 500 acres.

Protecting the habitat would also help other endangered species like the mountain sweet pitcher plant, bunched arrowhead and rare salamanders that live there.

“The southern population of the bog turtle will go extinct in the wild unless it is listed immediately as an endangered species,” the center said in its application.“The southern population of the bog turtle will go extinct in the wild unless it is listed immediately as an endangered species,” the center said in its application.

The Endangered Species Act has five factors when it considers whether to list a species for protection, and the southern bog turtle ticks all the boxes: “habitat destruction, overutilization, disease and predation, inadequacy of existing regulations, and natural and manmade factors."

The turtle is also a popular target for poachers and can sell for thousands of dollars on the black market, according to the application.

Poaching became such a problem that biologists in the region started carving notches into bog turtle shells so they’d be easier to identify and harder for poachers to sell.

“Rare turtles represent the fourth largest source of wildlife sold on the black market,” the center said. “While once sought as a delicacy or as a source for medicines, turtles are now mainly bought as unusual pets. Demand for rare turtles in Asia has skyrocketed, especially in the last five to 10 years.”

But Bill Shultz, a retired wildlife biologist who worked for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, said the species should be listed as “threatened” and not “endangered.” He wrote to regulators to support the petition to protect the turtle.

“Since this species will need significant management to maintain its population at current levels, a listing as ‘threatened’ will provide more flexibility,” he said in a letter to the USFW supporting the petition.

The threatened status would mean conservation workers could take the turtles for breeding or “head start programs” so younger turtles can have a better chance to survive to adulthood.

The N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission already lists the southern bog turtle as a threatened species and published a conservation plan in 2015.

Nonprofits, the state and the federal government are working on preserving the remaining mountain bogs. The Fish and Wildlife Service created the Mountain Bog National Wildlife Refuge, a patchwork of properties in the mountains to protect these unique ecosystems.

With the initial review finished, federal regulators will start a 12-month process to review the status of the southern bog turtle. That process includes reviewing the science and taking comments from the public before the turtles can be listed as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act.