What began as the construction of a new 240-bed behavioral health hospital on the grounds of the Austin State Hospital has turned into a minor archeological dig into the hospital’s 161-year history.

The Austin State Hospital – originally known as the Austin State Lunatic Asylum – was established by the Sixth Legislature in 1856 and opened its doors to a dozen patients in 1861. Its 95-acre campus, which exists alongside the Hyde Park neighborhood, is the oldest hospital of its kind in the state and the anchor of the 11-facility state hospital system.

D.D. Clark, the historian for the state hospital system, describes the campus as a place that began for treatment but eventually morphed into its own self-sufficient community, with its own on-site farm and garden and a more expansive 306-acre state dairy and hog farm to the north, which was located roughly where the Lakeline Mall Home Depot now sits.

“This building came up first and—as it was mentioned before—wings came off this building where the residents lived,” said Clark, standing under the trees in front of the original hospital. “The middle part was mostly administrative offices, and on each side, you had the residents and individuals who worked here. And from there, you had different buildings coming up to add additional residents.”

The location of the hospital, at roughly 40th Street and Guadalupe, was considered “out in the country” where residents could take advantage of the fresh air and peaceful living, Clark said.

“As the population grew, they built more buildings,” Clark said. “You would have your barns. You would have carpentry areas. Some places had furniture making. It was literally self-sufficient.”

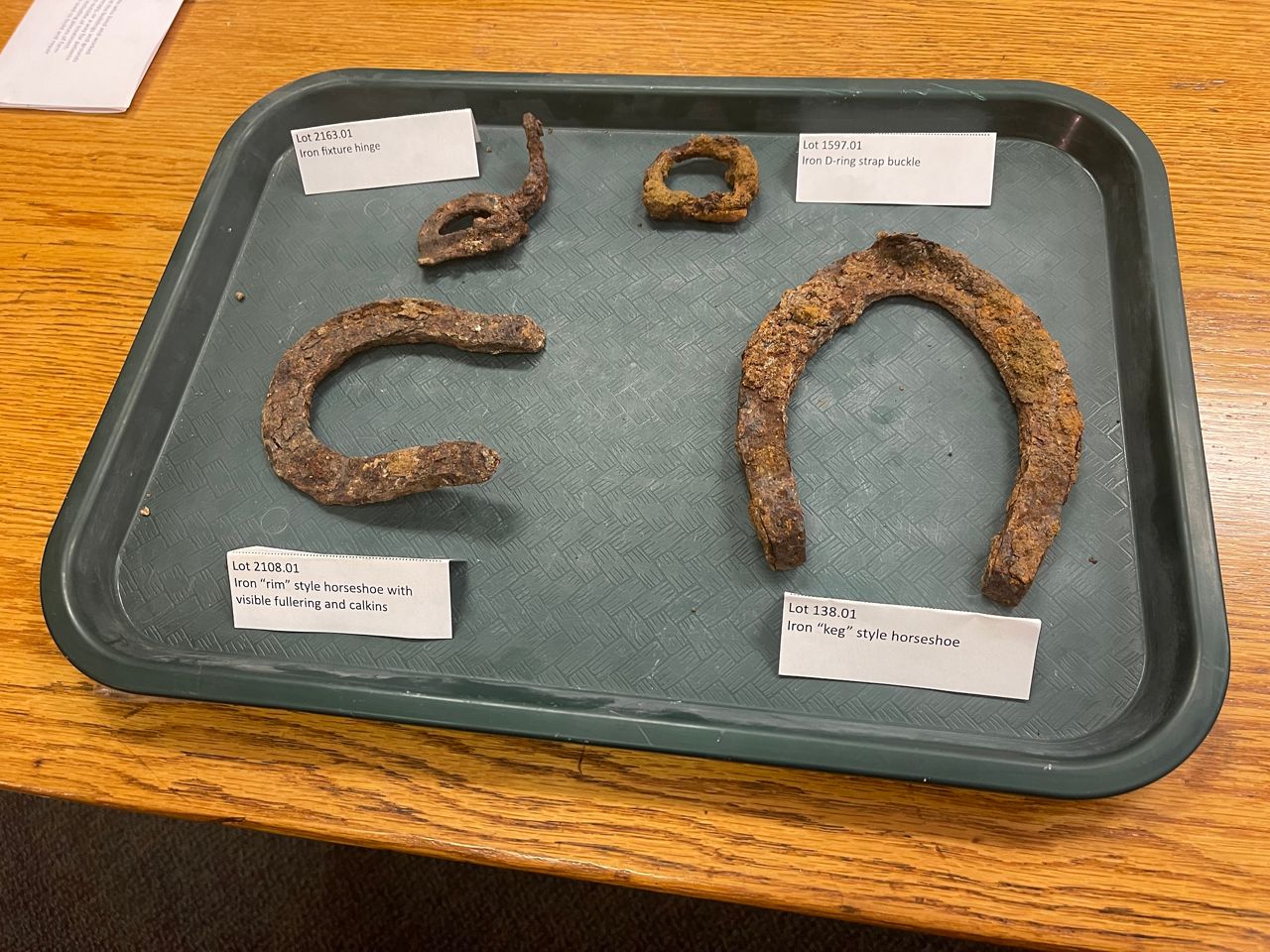

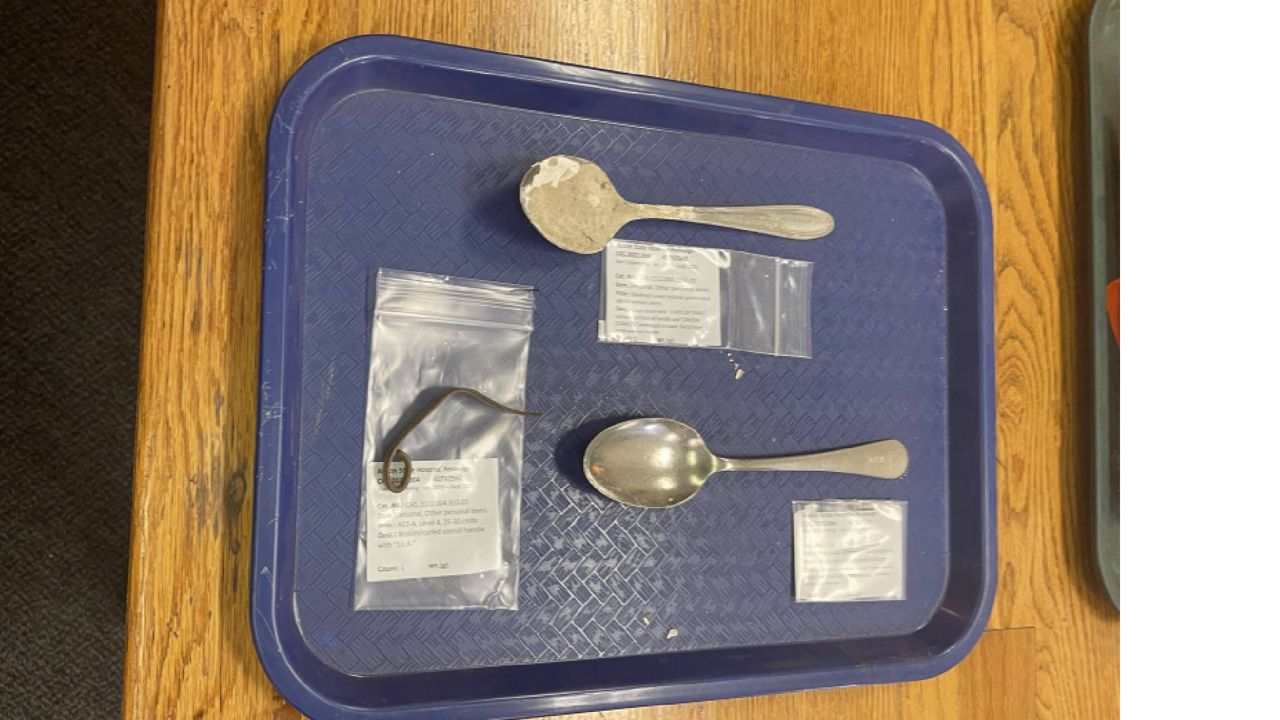

That’s why, looking at the display of the artifacts dug up from the site of the new hospital, you see horseshoes and mule shoes. There are farming and gardening tools. Spoons recovered from the site still have “Austin Lunatic Asylum” stamped on the handle, as inappropriate as that term is now.

“It was thought, at the time, that fresh air contributed to recovery,” Clark said. “So the outdoors were incredibly important. It was everything that was needed to occur in a recovery environment. Austin State Hospital brought all that together in line with the Kirkbride theory of recovery.”

Kirkbride was Thomas Kirkbride, a Quaker surgeon-turned-psychologist who advocated for a philosophy that treated the mentally ill with compassion and respect. Work, exercise and routine were highly structured at the hospital, according to the Texas State History Association. Some residents did laundry and mopping. Others did farming and harvesting. Higher-functioning patients often worked as staff members at the hospital.

Across the decades, the number of residents on the Austin State Hospital site, often referred to as ASH, grew to a population as high as 2,800 patients scattered across the many buildings on the property. By 1940, it was big enough to have its own school district. It eventually added the residents of the Texas Confederates Home.

“You’ll find many of these buildings are patient-care buildings,” ASH Superintendent Stacey Thompson said. “They all had a very specific population. So we’d have one building for adults that were here for short-term stays. We’d have another for adults who needed geriatric care. All these different needs were spread out across the hospital.”

Originally segregated, ASH integrated between 1958 and 1965. As outpatient clinics and community centers opened in the 1960s and 1970s, the population began to drop. By the 1980s, many of the on-site patients had been shifted to off-site treatment through Austin Mental Health-Mental Retardation. People would pass through ASH for treatment, but fewer than 500 lived on site.

Now, as the idea of recovery and recovery settings has evolved, the idea of a single site for recovery – the reconfigured $305 million 240-bed behavioral health center – has emerged. Construction on the facility broke ground in October 2019 and will be completed in November 2023.

Thompson did not expect the new construction – which will come with a partnership with the Dell Medical School’s psychiatry department – to uncover so much history. But as it has, Thompson has committed herself and her staff to preserving the long-term history of the hospital, with the help of Dr. King Davis and his students in the University of Texas’ School of Information.

“I didn’t know, when we started designing the building years and years and years ago… I thought, ‘Oh, this is such a cool thing,’ but I had absolutely no idea everything we would find,” Thompson said. “I had no idea we were going to branch out into this piece where we would actually preserve what was once here, and we were going to be able to take all that forward. That’s been unexpected and cool.”

Excavation on the new hospital site has gone as deep as 10 feet. Pieces of history uncovered on the site have been as small as single straight pin or a button and as big as home furniture, children’s toys and sewing machines, Clark said. It’s like uncovering a slice of history frozen in time, much of it matched up with the Census records of the time.

“It all speaks to the human nature of the individuals who lived here,” Clark said. “Yes, it’s a story about Austin State Hospital. But the message of this history is about a community, a society, where people to recover. There wasn’t a separation of families here, workers and residents.”

_(1))