NATIONWIDE — Captain Dennis Tajer has worked in aviation for 33 years, the last 28 as a pilot for American Airlines. Prior to that work, he served in the United States Air Force. He is also the spokesperson for the Allied Pilots Association, a union that represents 15,000 American Airlines pilots.

Tajer spoke with Spectrum News reporter Stacy Rickard about 9/11 and the state of the airline industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. A transcript of his responses are below. Some of the responses have been edited for clarity.

SR: What was your experience on 9/11? Where were you?

DT: I mean, clearly there was a — I hesitate to call it this, but it was truly, comparatively, a level of innocence and confidence in the fact that something like this couldn't happen. But I don't think anyone contemplated it. If anyone had written a screenplay and said, “Here, I've got this fictional story,” people would say, “That's over the top. That's not going anywhere.”

But it happened. Here it's 19 years now. And I was speaking with some pilots, and we were all around during that time, but it’s hard to process that. And I think you don't have to be a pilot to have this thought, but it doesn't feel like it was 19 years ago.

I was flying a trip with American Airlines, I was first officer at the time after about eight or nine years with American Airlines. And we were laying over in Albany, New York. So away from, of course, where the World Trade Center tragedies happened. But I have clear memory of getting a call from my spouse saying, “Are you are you watching what's going on?” And I was woken up out of a sleep after getting there late. And I said, “No, what?” and I turned on the TV and saw, of course, every station was covering it. And my memory at the time was seeing the billowing of smoke from the one tower and thinking, “Okay, someone just made a mistake in a small airplane or something.” I mean that was my half-awake thought.

When a second airplane hit, I started to process that something incomprehensible might be going on. And then of course the news spilled. So I went through everything that everyone else went through. As a crew member, as a pilot I went — I went immediately to, “What could have been going on in that airplane?”

We didn't know, but it became evident that this was something intentional and not set to one airplane. So I think at a time — now, we have tremendous emotion because we know what happened on those airplanes — but at that time, it was more of — as pilots, we go into, you know, protecting your passengers, and you go through that natural, “Okay what can I do to protect my passengers?” And this wasn't a normal emergency. So it left us in this this void, this black hole of not being able to process this, because our tools and our profession is to protect our passengers and when something like this happens, it wipes that all off the slate. And you just come out of your pilot, captain, first officer, flight attendant protective mode and you go into, “Okay, now I'm a human being and I can't process this.” So it was a very challenging time at the time.

And now, as you can see in this interview, and excuse my emotion in this, but it's still raw. And what helps me come out of that human moment both as professional, as a parent, and a son, and a part of our community is what we did after. And that is something that was truly heroic. Not only the folks that handled that emergency, handled that at the Towers.

So, my experience at 9/11, after seeing that and it becoming a reality, obviously the air system was shut down. Of course, my kids were young but they were asking questions. They weren't processing. I wanted to get home. Our crew gathered up and were looking for information like everybody else. Obviously the nation was frozen shut basically. But we came down to the lobby of the hotel and I remember the captain I flew with, and he was very compassionate and checked in on everybody. It was clearly shock that was still in us. But he sat down and said, “All right, I don't know where this is going, but I know one thing — I want to be here to help recover from this. So, there's nowhere to go, we could get in the car and drive home. If you want to, you can, I will assist you in that. But until and unless they tell us to just get back home, let's hold our ground. And when we start flying again, we'll be here and I don't know how many days that will be, but let's do this together. And if you— if you're not feeling comfortable doing that, then we'll take care of you.”

And that's exactly what we did. And there were other crews there, we’d met up with them. And every day, we would meet up, have meals together and talk and check in. So, it was just like our nation was doing, we were doing it from a hotel away from our families, like so many others were, but we were actually just readying ourselves to get back to flying, to get our country back up on its feet. So that's what was going on at the time.

SR: When did things kind of get back to normal? When did you go back to the routine day-to-day?

DT: Never. It’s never gone back to normal. The normal was pre-9/11. And thank goodness we've never gone back to that attitude of pre-9/11. That would be dangerous. So, everyone listening to this knows it's the “mental tattoo” of “if you see something, say something.”

That's just, it's in our fabric now and folks, people who were just kids then or haven't been born yet. Now it's not even thought of what the “normal” was. And even in this time of crisis, we have a diligence for looking for that threat. Because if you think it can’t happen, you shouldn't be in that airplane. Just like any of our first responders, our policemen, firemen, our military, you're always looking for, “it could happen again, let's be on the alert.”

It’s not out of paranoia, it’s out of the reality of “my job is to be the last line of defense.” And when you do that together, you can accomplish some amazing things. So I think that what we came to be more comfortable with was that this is our ever level of attention. And I hate to use the cliche of the “new norm” because norms usually get changed. But it was our new way of looking at doing business and our new way at conducting our day to day lives, whether it be on an airplane or in our communities.

So it's just the reality but you know what, we found a place where we could get back to our lives and shine and grow and raise families. And just like at that time, that human experience is nearly identical. There's a lot of fear out there, a lot of uncertainty. But every time we pull together and we start doing things, we say, “Okay, this is gonna work,” and it's proven itself to work. People feel more comfortable.

Just look at this coronavirus, a handful of months ago, people were locked down in many cities wondering if it was safe to go to the grocery store and now we actually have a way of conducting business and conducting our lives while this cloud hangs over us. And believe me, the winds are blowing — the clouds will move along. But we've got to just keep finding that next step to feeling like “Okay, I can still have a life while we battle this.”

So that’s the hope and the optimism I've always had and the men and women I fly with carry that each and every day, even when they’re a bit scared. We're human beings, you know, a bit fearful or uncertain. Our job is to ensure that we compartmentalize that, park that, because people are looking at us for that nod. Sometimes it's not even a word. It's being in an airplane when you go through some turbulence.

I've been in the back and I know it's okay, but it's a little bit rougher than normal. And I watch the passengers and their eyes go — if I'm in uniform, they'll look to me or they'll look to the flight attendants — and when they look back or they don't look unnerved or if they do look back and they kind of just nod their head, it’s like, “It's okay.”

So many things can be said by just being who you are as a professional and bonding with that human moment of, “I know how you feel, but I've been here before and it's going to be okay.” That means everything, no matter what side you're on.

SR: That’s a good segue into my next question: How did your attitude, you know, as a pilot kind of change after this? Did it ever get to a point where you were like, “Okay, now I feel secure”? Or is there a kind of level of uncertainty at each flight?

DT: Something that really assisted in our confidence was being a part of the process, just like with coronavirus. We're out there on the front lines, we’re the crews out there defending the security of the cockpit. We're very active.

Pilot unions, flight attendant unions, air traffic controllers, we had an aggregate voice to say “Hey we're going to be a part of this solution, whether it be aircraft security, airport security or the coronavirus — we're out there.” And it doesn't mean that we have dominion over opinion, it means that you've got to include us – we're on the front lines, we see things that you may not. It's just like any profession, if you're not there in a foxhole, chances are you might be missing a few things.

So that team effort, that collective effort, which is enhanced by unions, pilot unions, flight attendant unions that I mentioned, is critical to getting to a better place. Anytime you bifurcate out and separate out and you just say, “Hey, I've got all the answers right here,” you'll never get to a better place. So that was critical in the recovery and it'll be critical in this recovery as well.

And sometimes, just like the mental tattoo of, “if you see something, say something.” Well as professional pilots and flight attendants, when we see something, boy do we say something. Because the energy for us is not just protecting ourselves, it's our number one purpose in our profession and that's to protect every passenger on there. You're giving us your life's treasure when you get on an airplane or you send your family off to fly. And while you may not be at the gate anymore post 9/11, I can visualize you saying goodbye to your daughter, your son, your spouse, your mom, your grandparents after a visit, off to an airplane. You are handing them to me, to us, to protect them. And I have that same expectation when I send my family off to fly if I'm not with them. That is a trust that goes beyond any regulation, policy. But it affirms the importance of what we do up there.

You know, flying is an amazing thing, it's engineering brought in with the human being, and it has opened the world to us. But, don't ever forget — we don't as pilots, and this is not meant to strike fear — but we're up at 35,000 plus feet, it's extraordinarily cold up there, the winds are howling at 100 miles per hour on a normal day. That is not an environment that you survive in unless you have this miracle of a machine with engineering and human beings behind it. And our job is to ensure that it all comes together.

So I think sometimes we take for granted how easy it is to fly and the safety record. It's there for a reason. It's not there because we got it done and we're moving along, it's there because every single day it's all done to keep the risk and the safety margin as broad as possible. So that's something that makes this profession extraordinarily rewarding. When you work with a group of people who all have one purpose in mind and no matter what the distraction, they're all focused on that, it's like a symphony of support and security. And it's really an incredibly rewarding profession, but one it carries a tremendous amount of weight and responsibility. And there are a few people that step right up and I'm honored to work with them, even when we get knocked down. 9/11, coronavirus, I know that we always come out the other side stronger and better, and with a deeper core for that service that we provide.

SR: Recently, I’ve seen comparisons on social media of the 9/11 tragedies and the current coronavirus? What are your feelings toward that comparison?

DT: I've got to say, during this current crisis which is an enormous pandemic, it’s global in its touch, and there's been the just sad loss of hundreds, tens of thousands of people to this virus. It's often talked about, “Well after 9/11 and how did we deal with 9/11?”

9/11 is 9/11 — it’s different than this pandemic. This coronavirus is different; it's hit our economy differently. But people were murdered on that day in a very compacted timeframe. And it was horrific. And it's not to say that the loss of life is measured any harder on a family, but this was different. And we'll never forget. We won't forget this time. But I think that we should all remember that we always get to a better place, always, after something like this.

In comparison to the coronavirus, people have said, “What’s it like flying again,” you know and, “You were flying after 9/11.” There are similarities but there is an absolute canyon of difference. The level stress after 9/11 and getting on the first airplane and greeting coming on? Completely different energy, completely different. You're having immediate effect on you.

9/11 was what it was, you were murdered on airplanes. We had some close calls, the shoe bomber, the other person that tried to bring a bomb on right after that. But man, the American people, the globe stayed with it.

And the coronavirus, it has a similar feel, but it's different. It's not — I mean, it's just not as graphic. There’s just a different energy, there's just no doubt about it. And I hesitate every time I hear a comparison to 9/11. It's always said with respect, but it's mentioned more on the economic level and the destruction of an airline industry level and keeping our country's economy in an uncertain space, I get that.

But let's not forget that one was a horrific murderous event, which we got through and we've prevented from happening again. Any other one is equally as a moving human event for the loss of life, but it's different. And the one thing that does have a direct parallel is we will get through this. I have no doubt in my mind. We will get through it, and we will be in a better place as a result of it.

SR: Is there anything else you’d like to add?

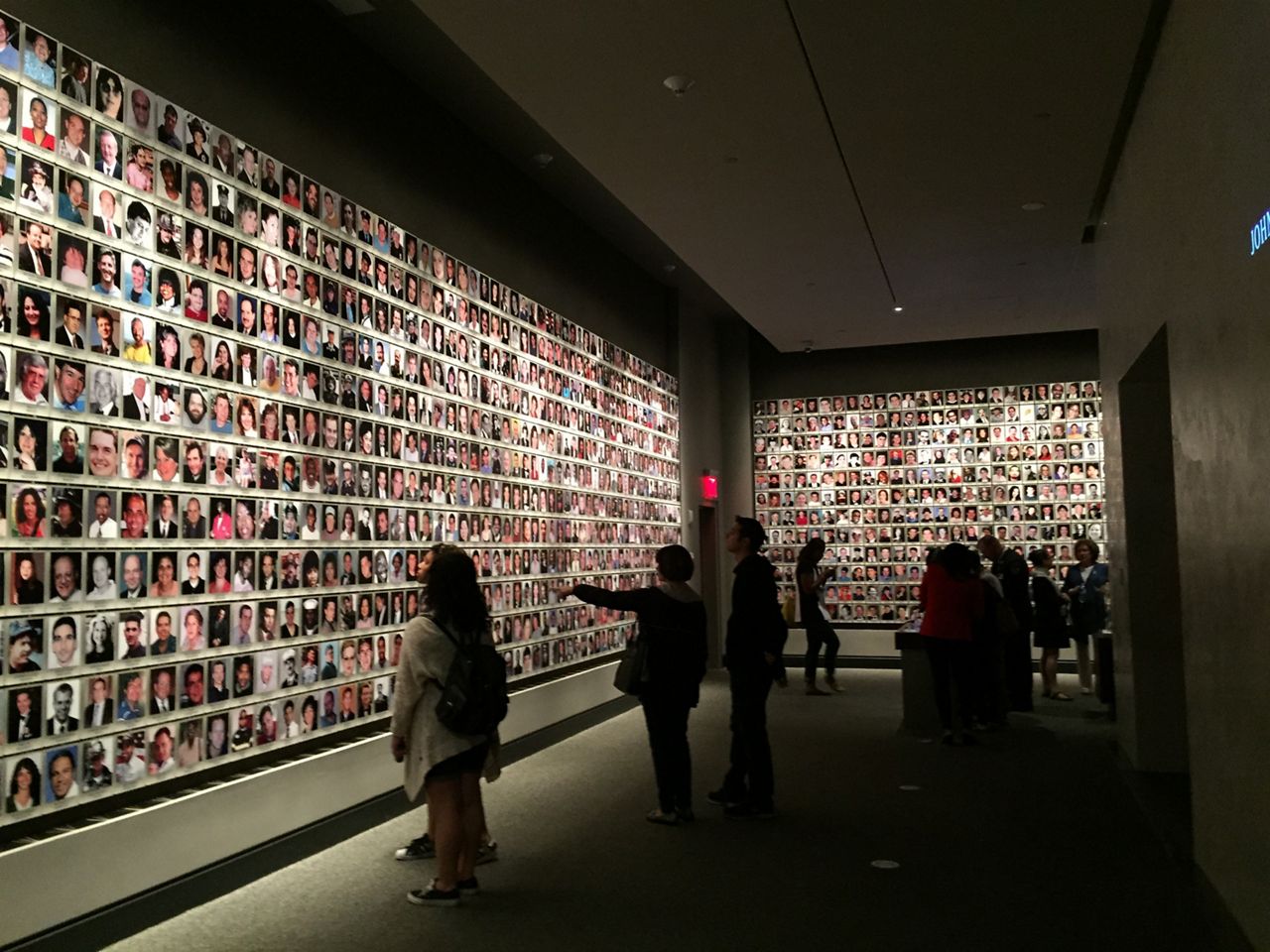

DT: I've been graced by being invited to an actual 9/11 memorial service [in New York] and met the firemen and police officers and I’ve been welcomed in and it's a very — it's a close fraternity. And I know those stories now, I've been there. And I’m sorry — I'm having a wash of faces and camaraderie that I've had, being blessed by having been invited to the actual memorial. And I encourage everyone to visit it. It will crush you and it will lift you up at the same time.

It's truly an amazing human experience, but be prepared. Brace yourself because you'll experience all of those emotions. I just start talking about it and as you can see, it can kind of shakes me. It brings me into the moment very quickly, and I can't help it. It is how I am as a person to express that and it comes out of my — sure, there’s sadness there — but it’s my pride and my awe for what the human being can go through and can come out of, even in tragedy. And I think it's beautiful and I think it's powerful and it can move more than an inanimate object, it can move a people.

SR: Do you have an experience from your time at the memorial with your fellow pilots you’d like to share?

DT: One of the pilots, who's one of our [Allied Pilots Association] representatives in New York to this day, was standing there and he goes, “You haven't been [to the museum]? You need to go.”

And the rest of the group said, “All right, who's going in with him?”

And I go, “I can go into the museum myself, it's okay, I'll be out in a minute.”

And they go, “No, no, Scott go with him,” and he came with, and he walked with me.

And we didn't say too much in the museum. But I turned to him and I just I was just in awe of everything. And you could touch the side of one of the airplanes, they have the piece there where I've done walk-arounds, it's the red, white, and blue of American Airlines and I could reach in and touch it.

It angered me, it made me smile and all of that. And through most of it, [Scott] was just there like, “You okay?”

I was like, “Yeah,” because he knew. He knew exactly what I was experiencing. And I get teary eyed at it because he knew and he didn't want me to experience it alone. And that's honor. And that's something that I still remind him of.

I say “Hey man, I love you, brother. Remember the museum?”

He goes, “Yeah.”

So, we left and came out and he said “You good?”

I said “I’m fine, thanks for being there with me.”

And we went on. And that was 10 years after right? So it continues to live in our hearts.