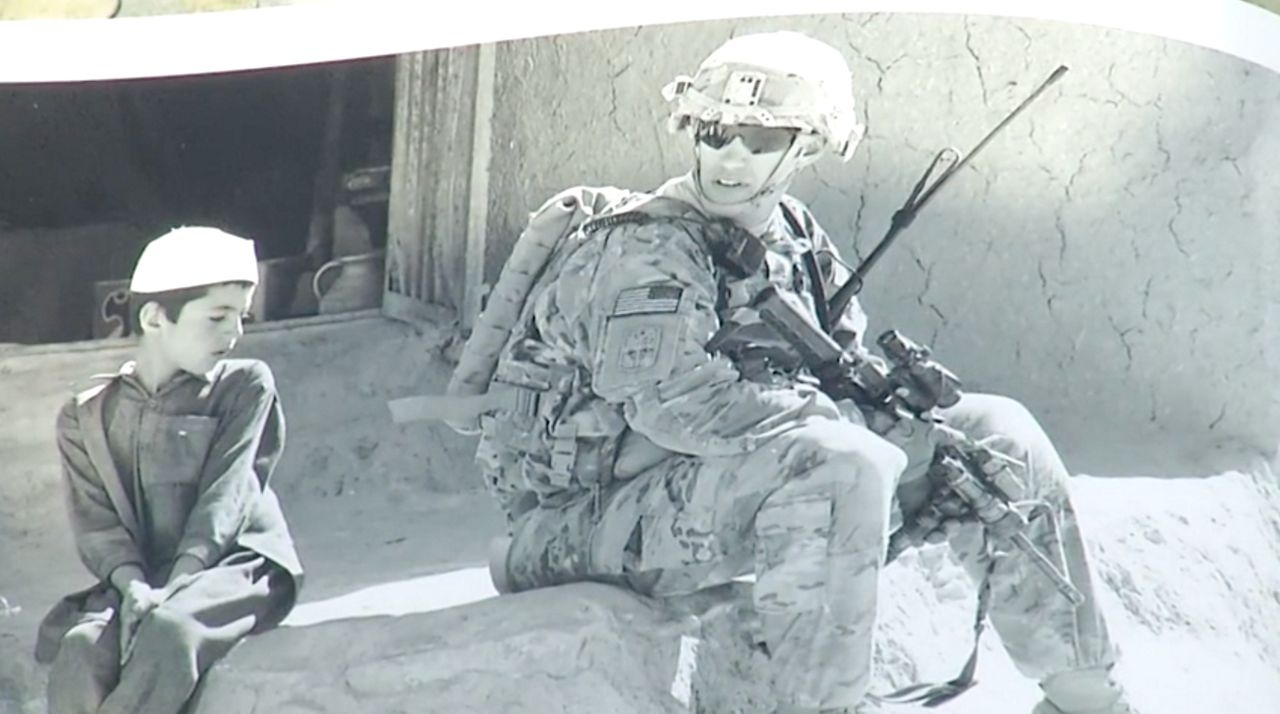

These writings by fallen U.S. soldiers, that were posted online and quoted as part of the Congressional record, are just two examples of entries wiped from a social media platform — an issue that robs families of memories and historians of eyewitness accounts during the first wars of the 21st century, internet data experts and military families say.

In 2007, the deadliest year for U.S. forces in Iraq, MySpace was the social media platform of choice around the world, and a place where countless dispatches from service members, including photos and videos, lived —but when MySpace began making updates, that material started to disappear.

The scale and scope of what has been lost seems to have escaped notice from the public at-large, alarming experts and veterans.

“We are in danger of losing everything we are saving right now digitally on rapidly shifting formats, rapidly shifting online services,” said Jason Scott of the non-profit Internet Archive, an online library with a diverse media collection that includes content from hundreds of millions of websites. “If we don’t play a part in being some amount of caretaker for our culture and our history that we are putting online, you know, our photos and our writings, and everything, we are facing everything from a power outage to a company merger ending what we have.”

Scott has been working to preserve content online for years at the Internet Archive, often receiving help from a separate group he helped start called Archive Team.

“There is a global concern that we made a wonderful bet, which was, ‘you can get everything you’re writing, everything you’re taking photos of out to the world, basically for free, instantaneous, for a long time,” he said, “but they’re going to call in that bet one day, and we’re going to discover that nothing is left.”

By its own terms of use, MySpace is not obligated to archive content. Even in its earliest years, the site stated:

MySpace.com reserves the right, in its sole discretion, to reject, refuse to post or remove any posting (including email) by you, or to restrict, suspend, or terminate your access to all or any part of the Website and/or Services at any time, for any or no reason, with or without prior notice, and without liability.

'Chance to start fresh'

In January of 2013, MySpace gave the public access to a redesign it was testing. People could still use the old version of the site at the time, but MySpace dropped that ability later that year in June as the redesign moved forward and ultimately cut off access to the old version of the site.

MySpace said photos, videos and music were transferred over at the time, but some other materials became impossible to access.

Blogs were also deleted, but for some time after this redesign. MySpace eventually provided users a way to log into an account and request their blog data, but anyone doing that would have to know that it was an option and still have access to their old account information.

MySpace acknowledged the wider data losses from the redesign, even as it was developing its blog recovery procedures, telling users, “Now is your chance to start fresh with a whole new audience.”

Multiple military families interviewed said they didn’t know about the blog recovery program.

Viant Technology Inc., MySpace’s current parent company, did not respond to multiple requests for interviews or answers to specific questions when contacted by email and phone.

“On the whole, if you put your data online and pay them for keeping it, there’s no real rule that they can’t just say, well we lost it, here’s a refund, or we lost it here’s no refund,” Scott said.

In 2018, the company unveiled changes to its terms of use and EEA privacy notice. MySpace explained it was making updates to prepare for new data protection laws from the European Union. Those laws, known as the General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR, were set to take effect on May 25 that year. MySpace’s policy updates included a list of the data types that had disappeared over the years, described as “no longer available for retrieval or download.”

One item of note on that list: blogs.

Missing dispatches

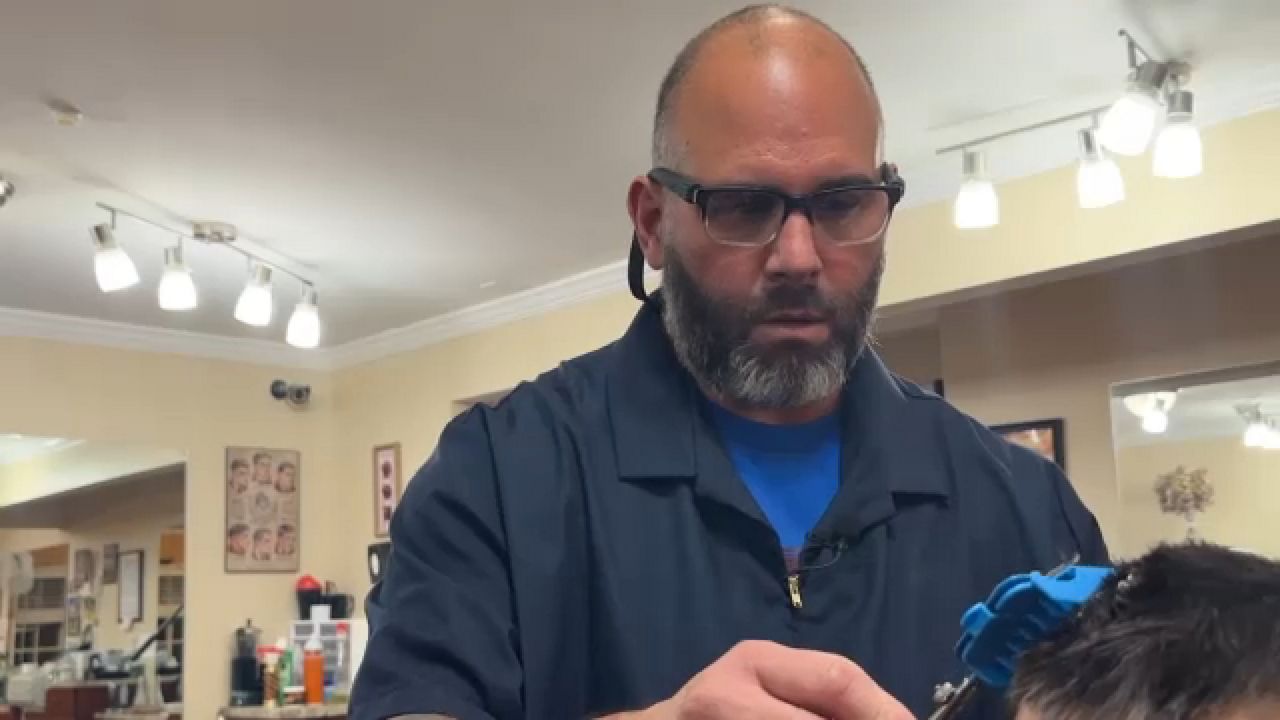

Mike Lang, a 37-year-old Air Force veteran from Milwaukee, says he blogged almost every one of the 500 days he was in Iraq between 2005 and 2007. All of that material is gone now.

“I obviously knew the rules, so I never posted anything classified, anything that talked about specific missions or specific people,” Lang said in an interview with Spectrum News 1.

Instead, he says he would often blog about how he felt on a daily basis. Deployed at the age of 18 and thrown into a master sergeant’s position as an airman, Lang found writing and sharing his experience online to be crucial.

“There were no days off. There were no weekends, there were no holidays, there was none of this, so basically, you’re just looking at a calendar, and hoping that you remembered what day it was, so to blog about this stuff gave me a sense of time.”

There are unsettled issues where the first-hand testimonies of those who served in Iraq and Afghanistan are critical to understanding the full scope of the problem — from high rates of PTSD to the use of burn pits during the war now leading to a health crisis.

Lang remembers writing about the burn pits. He says the pits were right next to his housing, and the smog was visible in the mornings.

“We would burn tires, lithium batteries, garbage, everything and anything we burned it if it could burn. So, it made no sense, we’d joke like ‘we’re all going to get cancer from this, because we’re burning stuff that isn’t meant to get burned in a 3000-degree incinerator, like ‘this isn’t a good idea,’ but well, we’re here, like, oh well, now we gotta deal with it.”

In MySpace’s case, the testimony of service members is one among many slices of what was lost. MySpace's user base included Iraqi refugees and victims of the Virginia Tech shooting. It included relief efforts in the years following Hurricane Katrina, and contemporaneous accounts from other tragedies, disasters and historic moments internationally.

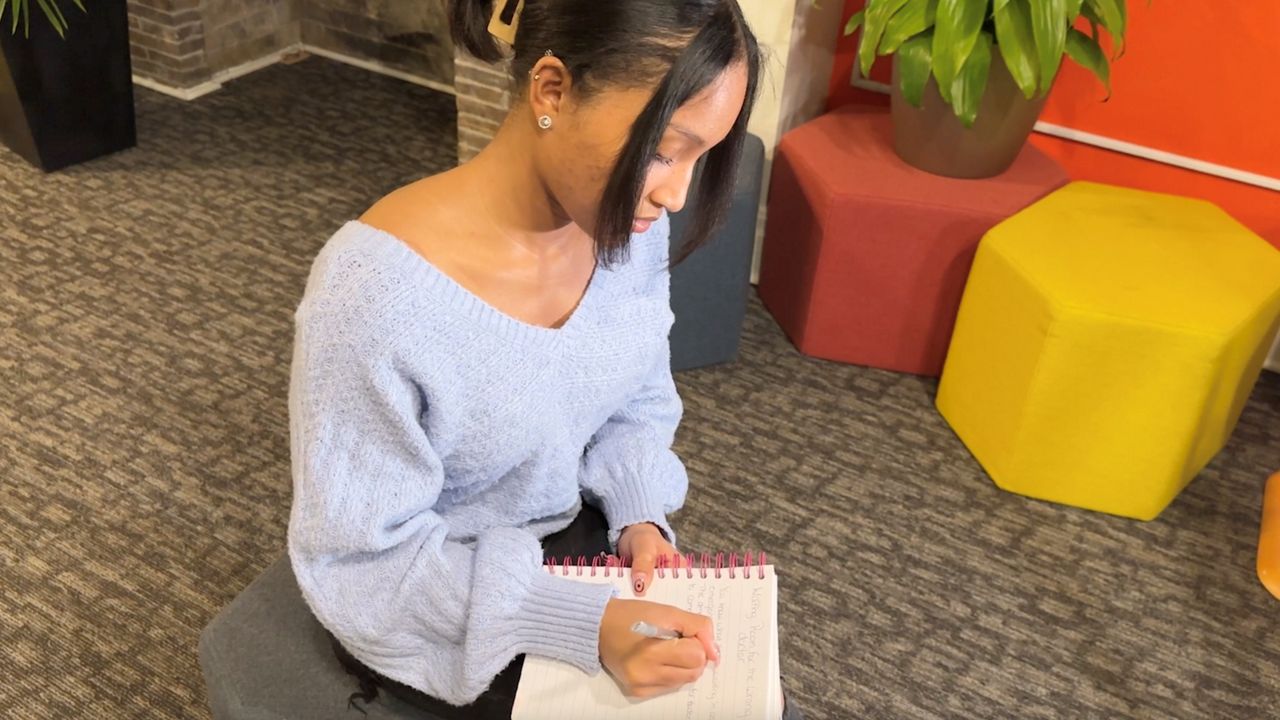

The lost writing goes beyond blog posts, with some families pointing to the personal conversations they’ll never see again. It’s a sentiment echoed by Kim Wilson of Getzville, New York, mother of fallen Army Staff Sgt. Billy Wilson III, who died in Afghanistan in 2012.

“We kept in contact on MySpace,” she said in an interview with Spectrum News 1. “I always said I can’t imagine in Vietnam and wars prior, not having that connection, you know? I knew if he logged on like one time a week, I knew, like, OK, he was OK. I couldn’t imagine going through all that and never hearing from him.”

Posts on MySpace offered a view into the complexities of soldiers at war, as reporters would describe and as the rare fragments that remain elsewhere show. Stories and essays and single sentence entries cut across a range of experiences and perspectives — from idealistic to hopeful, from critical to scathing, from routine moments to traumatic ones.

A wider problem

Losing access to digital history, and the history of a war specifically, isn’t a problem of one website, one type of content, or even one cause. Mass deletions of historic content can stem from the best of intentions. While trying to take down terroristic content, YouTube and Facebook’s moderation systems have also taken down potential evidence of war crimes, in some cases hundreds of thousands of videos.

Similarly, some of YouTube’s attempts to target hate speech accidently took down educational material on the Holocaust. In some of these cases, certain material was restored.

Technical issues, or a lack of preparation for technical changes, can play a role as well. As the nation marked 20 years since the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks, CNN explored how some of the most crucial journalism produced the aftermath of those attacks is becoming harder to access.

Billy Wilson’s parents lost conversations and photos with their son on Facebook as well as MySpace after Kim Wilson said someone on Facebook tried to impersonate Billy. After the family reported it to the company, they found all of Billy’s old material was gone. Meta, Facebook’s parent company, did not return a request for comment on that incident.

As politicians in the U.S. and across the world debate internet privacy rights of users — and companies weigh the potential costs of storing data, what happened to the words of service members in Iraq and Afghanistan, could happen again, experts warn.

“If we have a law passed, again, in total good faith, trying to protect people, or trying to make the world a little more accountable for the data they keep, it is not out of the realm of possibility that these companies will say, well I guess we’re going to get rid of the data then, and nothing can stop them,” the Internet Archive’s Jason Scott said. “They’ll just do it. So that’s a danger that we face in the future.”