RALEIGH, N.C. — Stigmas surrounding mental health affect people of all cultures and ethnicities, especially within Asian American communities. Studies have shown a troubling silence: a vast majority of Asian Americans with mental illness are not seeking help.

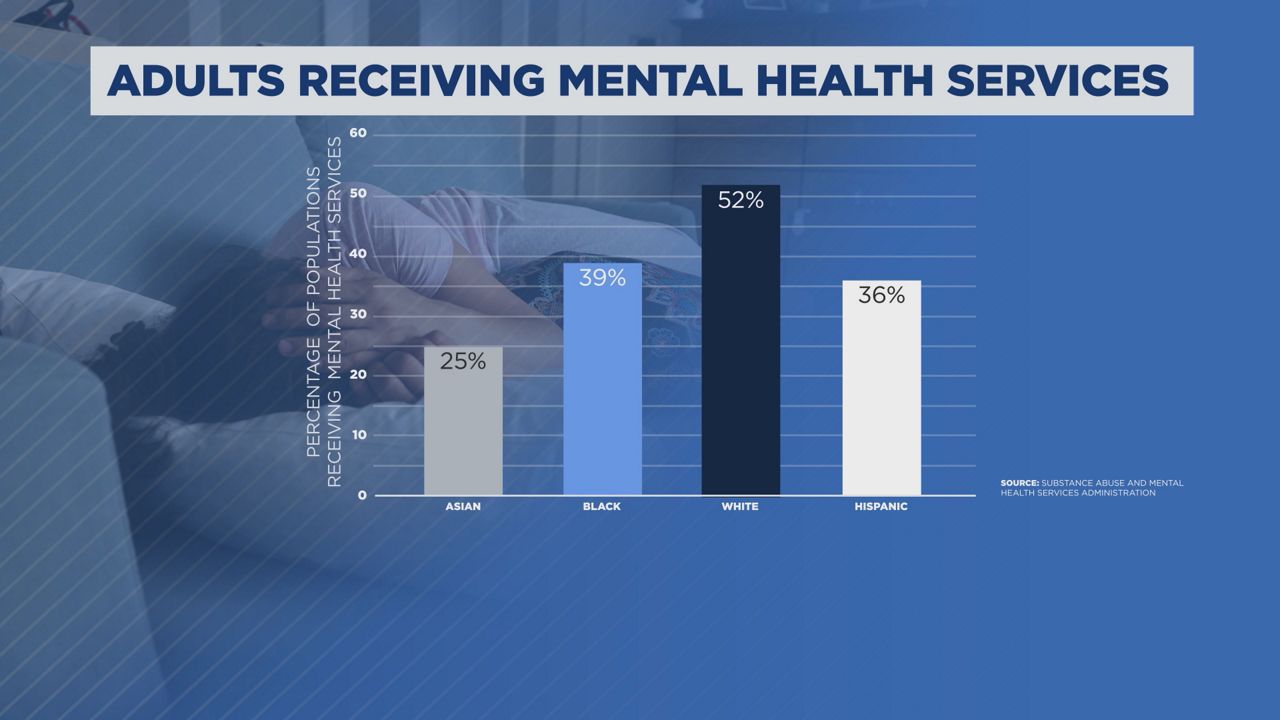

According to a report by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, just 25% of Asian adults with a mental illness received mental health services in 2021, a number far lower than any other ethnic group.

"There are two key things that really come into play," said Janice Cuaresma, a mental health counselor. "It’s the culture and family that contribute to that."

In many Asian cultures, there’s a strong emphasis on family honor and reputation, which can make individuals more reluctant to seek mental health help for fear of bringing shame or embarrassment to their family.

"Or maybe people come from a family where we don’t talk about our business with outsiders, or it’s taboo to talk about that with strangers," Cuaresma adds.

Cultural and social norms around mental health often result in it becoming a topic that’s not openly discussed.

“I didn’t really have that much exposure to mental health growing up,” Cuaresma said. “I didn’t really have words or understanding of what anxiety or depression was."

A turning point for her came during the COVID-19 pandemic. She worked in digital marketing in California for automotive clients like Toyota, Kia and Hyundai but resigned when a poor work environment left her feeling unfulfilled. The stress from difficulty finding work during COVID, coupled with her father’s Parkinson’s disease diagnosis, took a toll.

"I was not in a good place," Cuaresma said. "In talks with my partner, we kind of understood, this is becoming an issue. That was part of the impetus to get help."

But her own struggles in finding the right therapist led to a crossroads. Genuinely believing she could do better job, Cuaresma left a decade-long career in corporate America behind and returned to school for counseling. Now licensed, she’s settling into her new calling, opening pathways for dialogue in a community that often shies away from it.

"Some people may not feel that their clinician will understand their true circumstances," Cuaresma said. "And there’s also the language factor. Some people prefer to speak in their native language."

There are also differences between Western and Asian perspectives on treatment. For example, when it comes to addressing grief, Western therapy often encourages people to find meaning or a sense of closure in their loss. However, that might not work for a patient whose culture doesn’t emphasize those aspects of coping with grief.

"You’re more than welcome to decide if you want to make meaning or not," Cuaresma said. "Just in that example, you can see how these different values of Western culture can come into therapy."

Among her patients and sessions, she has noticed a hopeful shift. Younger Asian Americans are embracing a future where mental health is acknowledged, not hidden.

"The current generation feels like, hey, like I need to take action on this," Cuaresma said. "This is not something that I can ignore. This is something that I want to address."