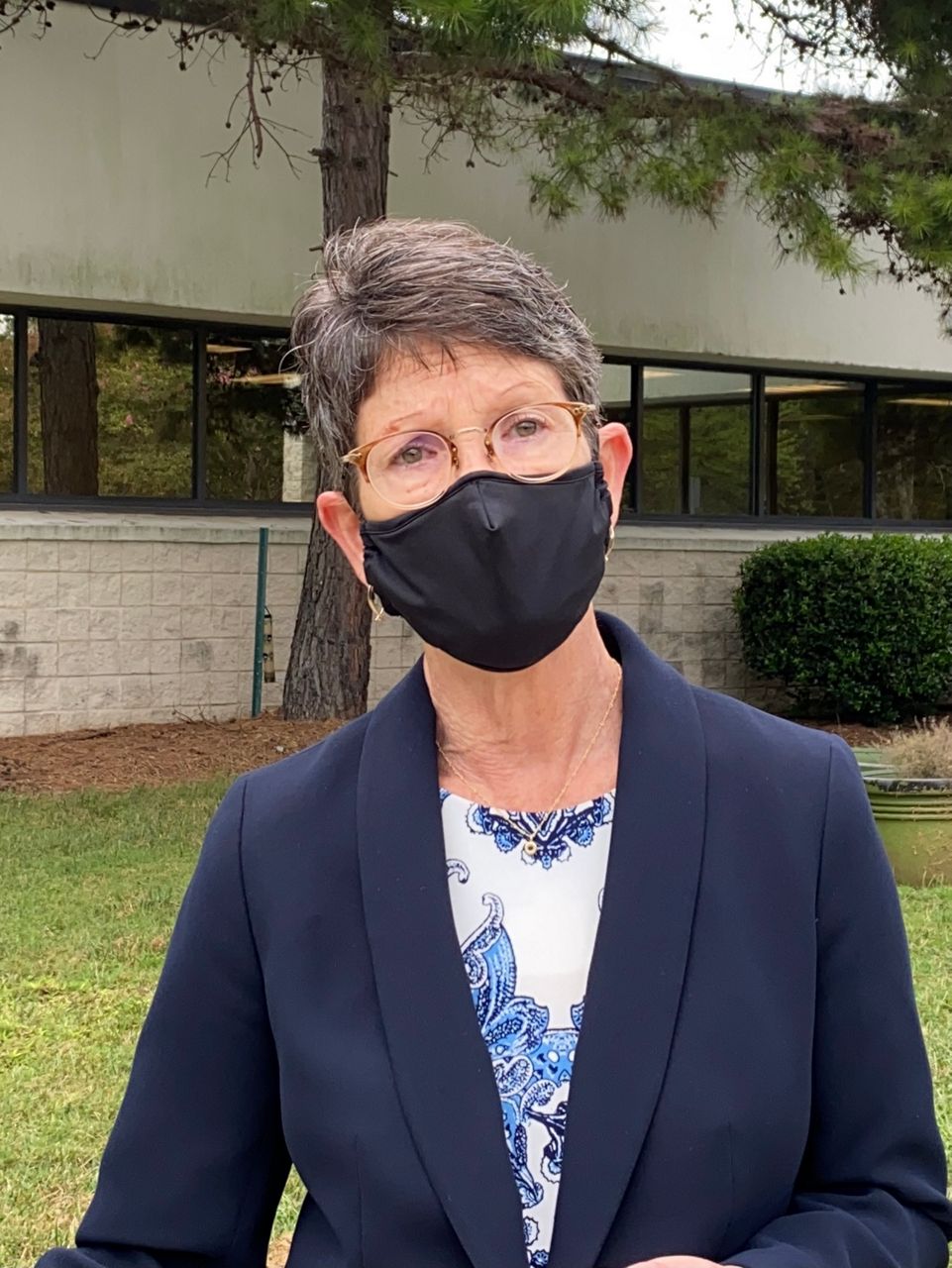

CHARLOTTE, N.C. — Gibbie Harris is getting ready to retire. Again. The Mecklenburg County health director came out of retirement about four years ago to lead the health department. And then the coronavirus pandemic hit. For the last 18 months, Harris has led the county’s response to COVID-19.

She’s been a public face for fighting the coronavirus in Charlotte and Mecklenburg County during a time when public health has become the number one issue facing the country and the world. It’s also taken a toll on public health workers, who have faced long hours and, increasingly, harassment and threats from people who are unhappy with mask mandates and growing rules around vaccines.

“It’s been challenging. Unfortunately, once COVID became a bit politicized, it made the response a little more difficult because people make decisions based on politics instead of on science,” Harris said, standing in front of the low-slung, unassuming headquarters of the Mecklenburg County Health Department.

“Recently, when we talked about a mask mandate at one of our board meetings, there were some folks there that were not happy with the decision, and they made that known. But that’s their right,” she said.

“This has been a trying time on all of us in public health, from responding cases, to leading a vaccination campaign, to responding to cases again,” said Mike Zelek, Chatham County Health Director and president of the North Carolina Public Health Association.

Over the spring and summer, North Carolina and the rest of the nation saw months of improving numbers. People saw the light at the end of the tunnel. But the delta variant, much more contagious than the original virus, changed all that just as schools were going back for the fall.

He said in Chatham County, just outside Chapel Hill, he hasn’t seen the divisive debates and harassment that his colleagues in other areas have felt.

“I think we’re fortunate here. In Chatham County we’ve gotten a lot of public support. I think there’s a lot of public understanding,” he said. “While we know that not everybody agrees with everything that we promote, we’ve seen a pretty good uptake in vaccines and masks.”

Zelek said he started as interim public health director in July 2020 and then was given the permanent job later in the year. Being a local public health director during a pandemic is the only way he’s known the job.

“That’s reflective of the nature of the work we’re doing right now. It can be very taxing and in certain communities there can be some pressure and unfortunately some harassment of public health staff,” he said.

Guilford County’s public health director, Dr. Iulia Vann, also starting during the pandemic. She began in her role in March 2020, just as the coronavirus reached North Carolina.

“Everybody needs to be able to share what their opinion is and that’s perfectly fine as long as they stay within certain boundaries and they’re not negatively impacting myself, my team and anyone else around us,” she said.

She hasn’t felt threatened to the point of involving the police. But, she said, “We are getting more aggressive comments recently because of our new mask mandate.”

“We do have a lot of upset community members,” Vann said. “We’ve heard some foul language that we haven’t heard before.”

Vann said she jokes with some of her colleagues that public health degrees should include classes in political science and communications to teach budding public health professionals how to deal with these issues.

“Learning how to be very diplomatic about the way that we’re presenting things, knowing some of those hot areas that we need to address very carefully, knowing some of the dos and don'ts in certain communities,” Vann said, “That has definitely been new for me.”

Gov. Roy Cooper decided to drop the statewide mask mandate over the summer, leaving decisions over masks to local officials like county health boards and school districts. With that, the protests have gone from the governor’s mansion in Raleigh to local officials around the state.

Cooper has said that leaving rules over masks to local officials can mean more buy-in from communities. Most North Carolina school boards have approved mask mandates. Some counties, including Mecklenburg and Guilford, require people to wear masks in indoor public spaces like restaurants and grocery stores.

Politics has colored the coronavirus response since the early days of the pandemic, when then-President Donald Trump criticized state lockdowns and criticized leading public health officials in D.C.

The nation’s leading infectious disease expert, Dr. Anthony Fauci, became a target of Trump’s ire, and that anger at public health officials filtered down to local communities in North Carolina and around the country.

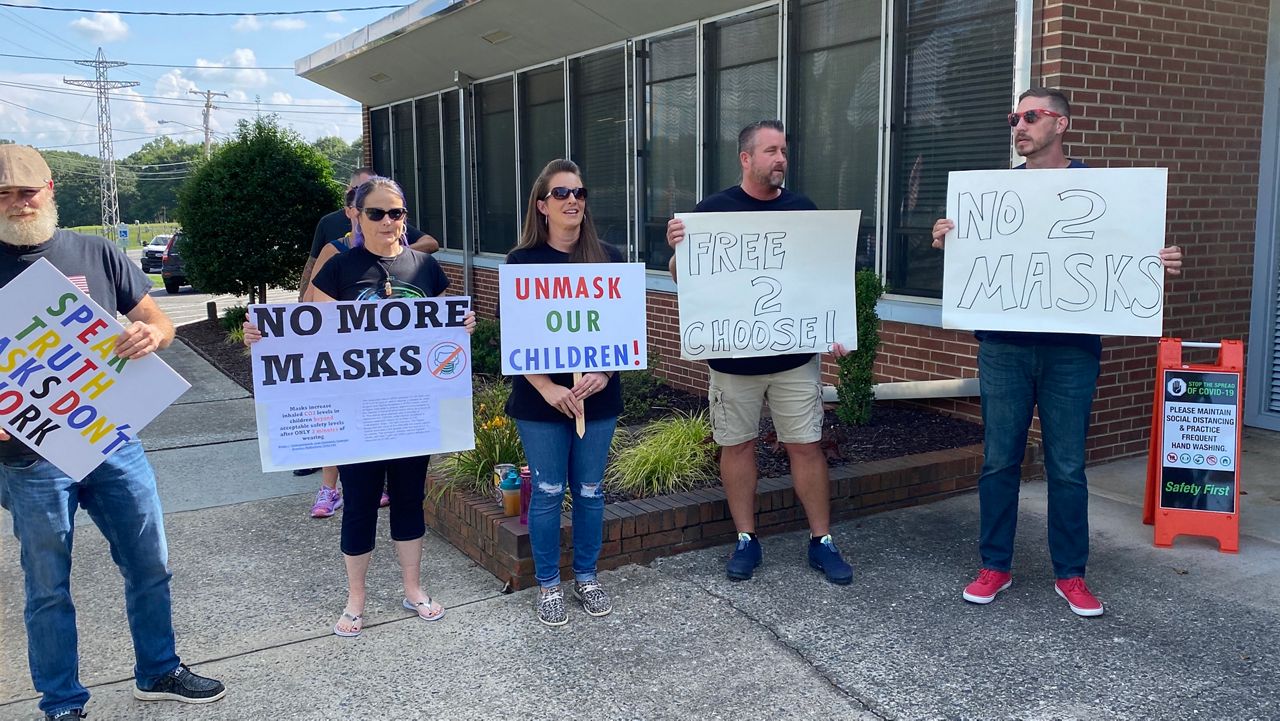

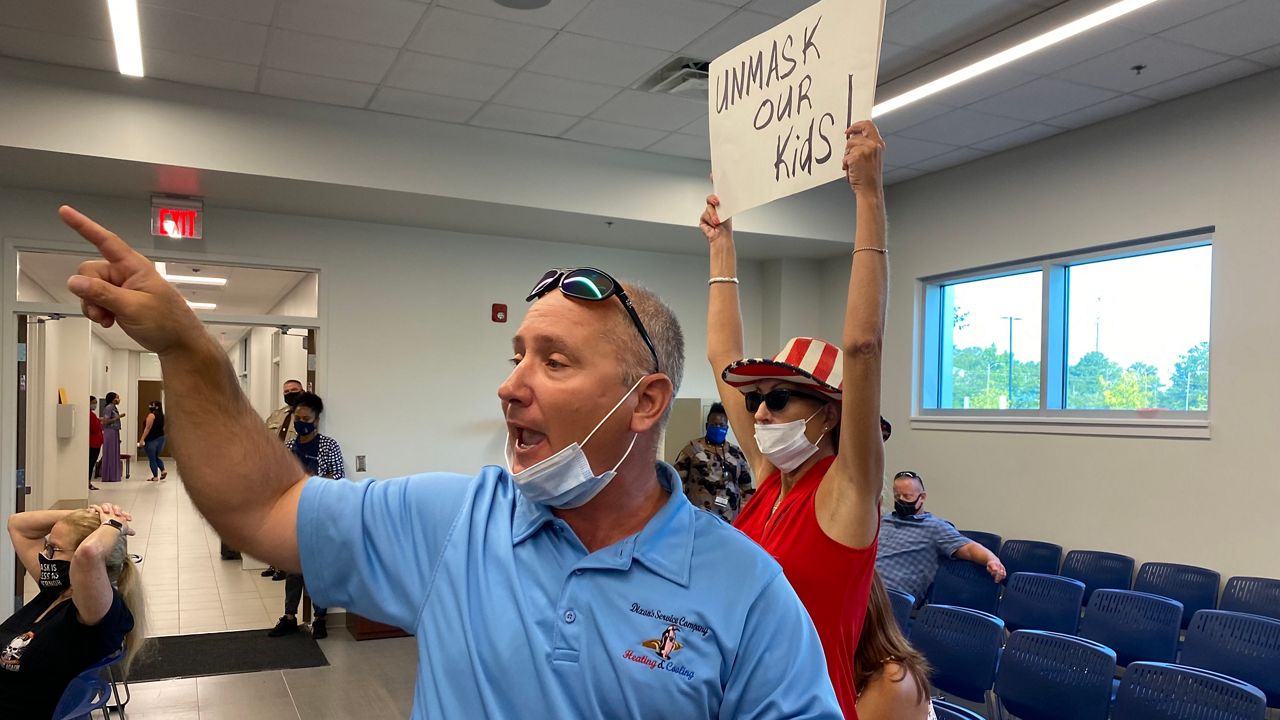

North Carolina’s school boards and public health boards have become the front line for the fight over face masks, which doctors and public health officials point to as one of the safest ways to control the spread of the highly contagious delta variant.

School board public comment sessions have turned into protests over school mask mandates. At least a dozen sheriff’s deputies were at a recent New Hanover County Health Board meeting on mask mandates. They had to remove several protesters from the meeting, even taking one out of his seat by force.

Harassment

Almost a quarter of local public health directors around the country have reported being threatened or harassed, according to a recent study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than half of the 26,000 public health workers surveyed reported suffering mental health conditions during the pandemic.

In Mecklenburg County, the harassment hasn’t been as bad as in other areas, Harris said. “They didn’t harass us, they didn’t follow us after the meetings or do some of the things I’ve seen happen in some other communities,” she said.

“I get a plethora of emails and some of them are grateful and thankful for the work that we do and some of them aren’t. But again, those are just emails. I’ve never had anyone act on anything. I’ve been grateful for that,” Harris told Spectrum News 1.

But it’s not the angry emails or heated public meetings that led Harris to her decision to retire. The time is right, she said. “It was never anticipated that I’d be here a long time,” Harris said. She has a deputy director that she’s been helping get ready to lead the health department, and he’ll take over when she retires in December.

Harris said right now much of her work is focused on two things: masks and vaccines.

For Harris and Vann, the Guilford County health director, fighting misinformation is a constant battle.

“There’s lots of different things that contribute to that misinformation. It’s great that lots of people have access to the internet and can understand things for themselves, but I just ask that people go to credible sources for that information instead of just reading whatever pops up on Facebook,” Harris said.

Vann recounted a story from some of her staff working in High Point. They were going door-to-door talking to people about the coronavirus vaccines and one man said he wouldn’t get vaccinated because he thought there were “crushed fetuses” in the vaccine.

There are no fetuses in the vaccine, but that shows the level of misinformation some public health workers face as they try to get more people vaccinated.

“A lot of mistrust when it comes to the information we’re putting out, the recommendations that are being distorted and questioned,” Vann said. “When we’re talking about prevention of sexually transmitted illnesses, for example, there are not a lot of protests out there if someone should wear a condom or not.”

She said she recently received an eight-page letter on why masks don’t work. “I felt like that was important for me to understand where they’re coming from,” she said. The information in the letter was wrong, she said, but she wanted to understand that for the next time she has a conversation with someone who opposes masks.

Some of the misinformation and mistrust has been discouraging, Vann said. But she and Harris both said there have been a lot of positives too: people are thinking more about public health more and they’re building new partnerships around their communities that would not have been possible without the pandemic.

“This pandemic, in a way, has brought our community together around issues and around concerns broader than COVID, but specific to COVID,” Harris said.

They both said they hoped those partnerships and the trust they’ve built with new companies and organizations will continue after the coronavirus pandemic gets under control.

The coronavirus pandemic has been a defining fact of life for most people over the last 18 months, and it doesn’t appear to be going away anytime soon. The vaccine was not a silver bullet.

“I don’t think we’re going to eradicate COVID-19, the coronavirus. What we need to be able to do is manage it, just like we do other viruses,” Harris said. People get flu shots because they help manage the annual flu.

“We don’t get rid of the flu every year, it comes back, it mutates, it changes, and we have to change our vaccine to address the strains we’re seeing. We’re going to see the same thing with COVID, I believe,” she said. “The challenge is getting enough people vaccinated so we can manage it, so that it’s not creating the surges that we’re seeing right now, so we’re not seeing our hospitals being overwhelmed.”

As of Monday, about 62% of adults are fully vaccinated and another 5% are partially vaccinated, according to data from the state Department of Health and Human Services.

Public health officials around the state continue to work every day to get more people vaccinated, despite long hours, misinformation and harassment.

“These are true public servants out there. They’re doing everything they can to keep the public safe in these challenging times,” said Zelek, in Chatham County.

“I think we were all feeling ready to be done with this pandemic,” he said. “It’s unfortunate when folks take out that readiness on public servants who are working so hard to get to that end of the pandemic.”