BAYBORO, N.C. — When Lynn Lewis got back to work after the Christmas holiday last year, something wasn’t right in her corner of the Pamlico County Courthouse.

The computers weren’t working. She figured their vendor had some sort of glitch. Lewis said she didn’t worry about it, at least until an email came through that afternoon. The company that runs the county’s property database had been hacked.

As the Pamlico County Register of Deeds, Lewis is responsible for all sorts of records: births, deaths, marriages, property sales and other real estate records. The county uses a vendor to handle the complicated software that keeps track of property records. That’s who got hacked.

Lewis’ office, along with five other registers of deeds in North Carolina and more than 100 others around the country, all got knocked offline.

“We had paper backups, so we were still able to function. It was slow going. But we were able to function, and the attorneys could update titles if they chose to. They can actually come into the office to still record the documents. So we were not dead in the water, so to speak. But it was a slow-going process,” Lewis said in a recent interview.

The company, Ohio-based Cott Systems, sent out a public statement days after the attack: “On Monday, December 26, Cott Systems identified some unusual activity on our servers. In an abundance of caution, we disconnected all of our servers to isolate that activity within our environment.”

“We then immediately engaged cyber specialists to investigate the event, and they began a forensic analysis. It has been determined that Cott Systems is the victim of an organized cyber-attack,” the company said.

It was a ransomware attack. That’s when hackers, typically an organized group operating out of Russia or another far-flung country, lock down a website or system on the cloud and demand money to restore the data.

Pamlico County is not a typical scene for an international cyber-ransom plot to play out. It’s a rural farming area, east of New Bern on the Pamlico Sound. The population is less than 12,500, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

The Register of Deeds office takes up a corner in the back of the small courthouse in Bayboro. Lewis, the elected Register of Deeds, grew up here. She went to the local community college. Lewis said she’s worked in the office since 2002 and became the Register of Deeds in 2012.

The records room in the Pamlico County Courthouse is lined with dark red registers. Lewis has property records here dating back to 1872. She still keeps paper copies, along with storing everything in the cloud.

So when the hackers hit that cloud software, she knew what to do. Being in a hurricane-prone coastal community, Lewis keeps an emergency preparedness kit. But instead of flashlights and bottled water, this kit has everything she needs to do to keep the business of official records moving during an emergency.

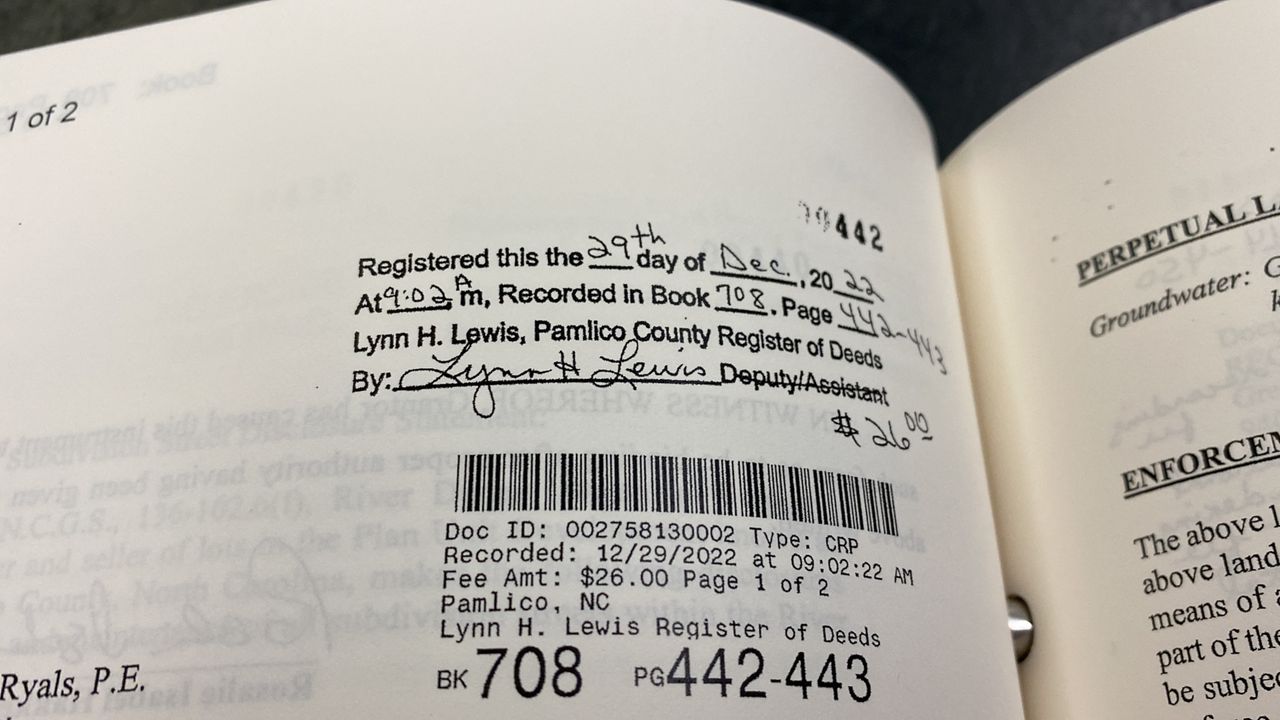

Her kit includes paper forms and a custom-made stamp to record deeds and vital records. When the system went down, she pulled out her backup kit and got back to work the old-fashioned way with paper and pen. And that special Pamlico County stamp.

I did always have this kind of gut feeling that something like that would happen,” Lewis said“I've always had a feeling that the vendor may get hit. And it's not just, you know, my vendor, it could be any vendor, no one is going to be exempt from this happening to them. But I did always have this kind of gut feeling that something like that would happen,” Lewis said, standing in her records room surrounded by 150 years of property records.

“That's one reason why I have chosen not to go paperless. And that's not an option in a lot of the larger counties because of space restrictions. But that was my reasoning for not wanting to go paperless, and it proved to be very beneficial during our cyber attack on the vendor,” she said.

This kind of thing is not uncommon. Attackers target government agencies, school systems, universities, and private-sector companies. Some attacks get extensive news coverage and can have widespread impact. Many others go unnoticed by the public.

One of the highest profile ransomware incidents involved the Colonial Pipeline in May 2021. That attack shut down gas shipments and sent prices at the pump skyrocketing on the East Coast.

Another high-profile hack, this time in 2020, used an exploit to get into software from SolarWinds, Microsoft and VMware. The hackers got access to several departments in the federal government. They also broke into computer systems for NATO, the United Kingdom and the European Parliament.

Investigators said a group backed by the Russian government was responsible for that attack. The hackers had access to the systems for months before being discovered, officials said.

But some groups go after much smaller targets.

Gaston College, in Dallas, North Carolina, fell victim to a ransomware attack on Feb. 22. The college is still working to get all its systems back up and running, according to the school.

A month later, the school’s four campuses still didn’t have wifi and some computer labs were still closed.

Chatham County got hit with a ransomware attack on Oct. 28 2020.

“As a result of the incident, the County lost the use of its computers, internet access, office phones and voicemail. The County acquired loaner laptops from other counties, towns and Chatham County Emergency Management,” according to the county.

It took months for the county to get everything back online.

“Forensic analysis revealed that ransomware entered the County network through a Phishing email with a malicious attachment. The threat actor, identified as DoppelPaymer, acquired data from a limited number of County systems,” the county said in a February 2021 update.

According to the FBI, the same group hit a hospital in Germany and a community college in the United States.

“As of February 2020, in multiple instances, DoppelPaymer actors had followed ransomware infections with calls to the victims to extort payments through intimidation,” the FBI said in an alert. The hackers would call victims from what appeared to be a U.S. phone number and claimed to be from North Korea.

The pattern is generally the same in these types of attacks. The hackers get access by getting an unsuspecting person to click on a link or download an attachment from an email, called “phishing.” Then they’re able to leverage that to get broader access to a system. Once an experienced group of hackers gets in, they can lock down and encrypt the system, demanding a ransom to unlock the data.

A report from the North Carolina Department of Justice, released earlier this year, said almost half of all reported data breaches in 2022 involved ransomware attacks. The state DOJ collects data on these attacks from state agencies, local governments and businesses in North Carolina.

For the first time in more than a decade, the number of computer security breaches fell in 2022. The DOJ reported 2,009 data breaches in 2021, and 1,900 last year. Those data breaches last year affected more than 3 million people in North Carolina, according to state Attorney General Josh Stein.

Of those data breaches, more than half were against private businesses. Only about 50 targeted local and state governments. These numbers also include when companies or governments accidentally release private information.

Reports of data breaches, malware attacks, computer intrusions and similar issues for state and local government go to the North Carolina Department of Information Technology.

Three years worth of data reported to NCDIT shows constant reports of phishing attempts, system intrusions, malicious software and compromises of system integrity.

Spectrum News 1 received the heavily redacted spreadsheet in a freedom of information request to the department. The data covers three years, from October 2018 through October 2021. It took the department the better part of a year to respond to the information request.

The data includes more than 130 reports of malware incidents in state and local government over the three years. Ransomware is a type of malware. Inclusion in the database does not mean the attack was successful.

The data includes an Oct. 28, 2020 report from a local government about a malware attack, the same day as Chatham County’s ransomware attack. But the details are heavily redacted.

In early March 2020, Durham, both the city and the county, were victim to a ransomware attack. That attack also appears to be listed in the data, given the date, location and type of incident. Reports later blamed the attack on a Russian criminal gang.

“Everybody is being constantly probed and constantly tested to see if their solutions are patched and their technologies are current,” said Eric Zach, chief information security officer and interim deputy state risk officer.“Everybody is being constantly probed and constantly tested to see if their solutions are patched and their technologies are current,” said Eric Zach, chief information security officer and interim deputy state risk officer.

To help local governments respond to the constant threat of cyberattacks, the state formed the North Carolina Joint Cybersecurity Task Force. Gov. Roy Cooper last year signed an executive order last year to create the task force to help state agencies, school systems, universities and local governments when they get attacked.

"The invasion of Ukraine and the threats of Russian inspired cyberattacks remind us of the cybersecurity threats that already exist every day," the governor said when he signed the order.

"It’s more important than ever for us to work together proactively to prevent these crimes and respond quickly when they occur, and this Task Force is helping us do that," Cooper said.

The task force includes the state Department of Information Technology, Emergency Management, the North Carolina National Guard and the state Local Government Information Systems Association Cybersecurity Strike Team.

For people like Lynn Lewis in Pamlico County, she doesn’t have the resources to deal with the constant threats in cybersecurity.

“Sometimes they just don't have enough people to handle a full incident response type procedure. So we come in and just offer our staff as an augment to the reporting entity and give them services if they need it,” Zach said.

In North Carolina, it is illegal for state agencies and local governments to pay a ransom for a computer system locked down by hackers. The General Assembly passed the law in 2022 as part of the annual budget package – North Carolina became the first state to ban paying ransom.

The law wouldn’t have impacted the case with Pamlico County Register of Deeds. In that case, it was a third-party vendor that was held for ransom. But the law specifically bans state and local governments from paying ransom to hackers.

Zach said it can be easier to just pay the ransom since, in many cases, it is covered by insurance.

“We don't do that, because it adds to the cycle, right? It encourages the threat actors to continue doing what they're doing cause they're getting their money that they're looking for,” he said.

“We don't do that across the state,” he said. “We never recommend that anyone pays ransoms.”

Cybersecurity threats, whether that’s from ransomware or stealing data to sell on the dark web, are not going anywhere.

If anything, the attacks grow more sophisticated everyday.

For Zach, with NCDIT, that keeps the job interesting.

“The fun part of being in cybersecurity is how much it changes,” he said. “The not-fun part of that is, you have to keep up with all those changes.”

Backing up data and systems is key. If a local government has a backup, it can get systems restored when they get held for ransom.

In Pamlico County, Lewis takes her job as the county’s custodian of records very seriously. And that means lots of backups, on paper and digitally.

“Back up, back up, back up, no matter how many redundant copies you have, keep all your backups,” she said.

“I want everybody to know that our records and Pamlico County, I spot check them, everything seems to be there and they seem to be OK,” Lewis said.

“You know, our vendor does do full redundant backups of our data, so I feel comfortable that none of our data was missing,” she said. “I do get a backup from them, a CD or flash drive, of all of our data annually as well, which I will try to get that changed to get it quarterly.”

So even when the world of international cybergangs hits a rural county on the Pamlico Sound, sending a government office back to using paper and pen, they’ve got the backups in place to get things back up and running.

)