Have you ever traveled down the highway and suddenly realize you don't really remember any of the past couple of miles?

Or maybe you've headed home from work and needed to run a quick errand on the way, only to miss the turn and not realize what happened until after you've pulled into the driveway.

Our brain often goes on auto-pilot, and if that happens with a child in the car's backseat, the consequences can turn tragic.

A vehicle basically becomes a greenhouse on a sunny day. if you’ve spent any time inside a greenhouse when the sun is beating down, you know how stifling the heat gets–and that’s even with the benefit of large fans blowing the air around.

The inside of a car turns unbearably hot quickly, and it’s not just on sweltering days. Those just give it a head start. Even on a sunny 70-degree day, a car’s interior can rise above 100 degrees in less than half an hour.

As the sun shines into a vehicle, the interior absorbs the light and heats up. That heat can’t go anywhere and stays inside the car, making heat continue to build.

On average, the temperature inside a vehicle will jump nearly 20 degrees from the outside temperature in 10 minutes, and much of the temperature rise happens in the first 30 minutes.

After about an hour, the air temperature levels off. However, a person’s body temperature will continue to rise.

Cracking the windows makes no difference. In less than an hour, the inside temperature was the same, as if the windows remained closed.

It's easy to understand how dangerously hot the inside of a car gets on a sunny day. What's harder to understand is how our brains can make even the most attentive parents or caretakers experience the unimaginable.

Yes, says neuroscientist David Diamond.

Whether it is the lunch you packed for work but left in the fridge at home, or your beloved infant strapped in a back-facing seat in your car, Diamond says anything–even a small person–can be forgotten for a time. He says it is part of the human experience.

"I'd say about 70% of the people will put children's lives in a separate category and they will say, 'you just don't forget that your child's in the car.' And those are the people that I actually think are most vulnerable because they refused to do anything to help remind them that their child's in the car," said Diamond.

Diamond, a neuroscientist at the University of South Florida, has studied the brain and memory for 40 years, often serving as an expert witness in trials where police have charged parents for the murder of their children – many guilty, he says, of simply forgetting.

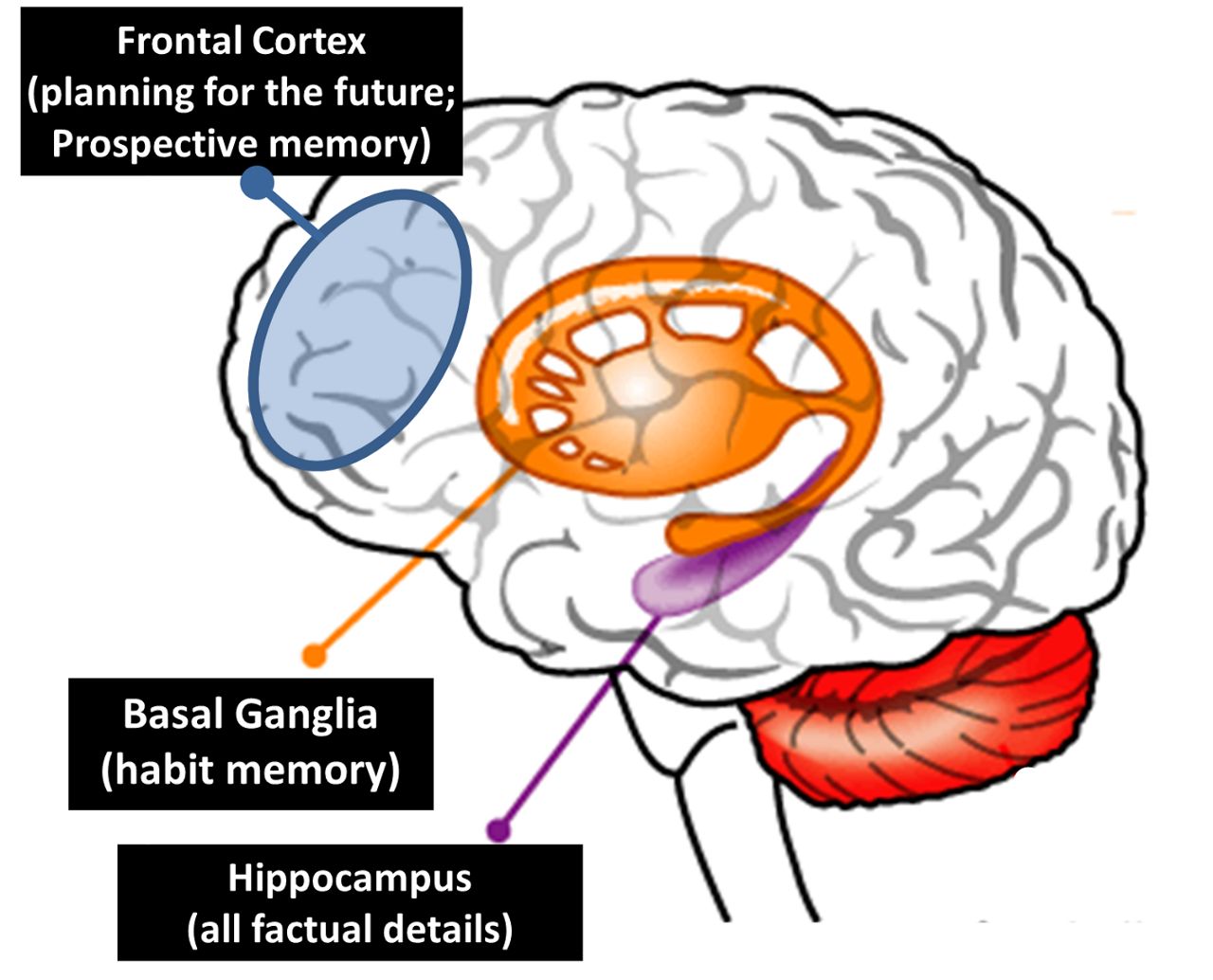

Diamond says it all boils down to three structures in the brain that compete for dominance: the basal ganglia, prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus.

The basal ganglia runs what Diamond calls the "habit memory" system, handling the mundane things we do without thinking, like allowing a driver to get home from work with barely a thought of the route.

The hippocampus handles all the new information that comes in and new tasks that must be done. It works together with the prefrontal cortex, which handles planning and strategy, in the "prospective memory" system.

Diamond uses a basketball analogy: "These three structures are working together, allowing the player to drop the ball, keep track of the score and strategize. Same thing happens when we're driving in a car, automatically our basal ganglia is getting us from point A to point B, listening to the radio, we're thinking about what we're going to do later today, we're having a conversation with someone," said Diamond.

But often the stresses of life and lack of sleep can force your hippocampus to focus on the issues causing the most anxiety.

"Under normal conditions, without the stress or sleep deprivation, you can easily forget what you plan to do on the drive. This is actually another area of my research. The hippocampus and the frontal cortex [are] extremely susceptible to stress, and its functioning is impaired by stress. So we become more forgetful when we're stressed. It's harder to strategize when we're stressed," said Diamond.

When your brain is in this survival mode, more neutral memories are pushed into the background. And old memories may become "false memories," convincing you that an important task like dropping your child off at daycare was already done.

Diamond advocates for Congress to pass the Hot Cars Act, a high-tech approach he says would mandate all cars be equipped with child detection systems.

Diamond says the technology is relatively cheap and integrates well with other systems already present in cars, like seat belt detection programs.

More broadly, Diamond suggests people take steps to remind themselves of things that are important, like setting alarms on your smartphone.

"You've got to sort of accept that this is the way the brain works, that the basal ganglia takes over," said Diamond. "What I would recommend is you put a little stuffed animal in the car seat and whenever you put your child in the car seat, take that stuffed animal, put it right in the front, in your view, and that stuffed animal would be there only when you’ve got the child in the car. Or, some people say put your cell phone back with the child. But use something that you would actually need when you get out of the car."