When most people think of ice and seasons, naturally, winter comes to mind. Indeed, wonderful songs like “White Christmas” and “Winter Wonderful” are about enjoying that white blanket of icy snow that we in North Carolina are accustomed to seeing a few times during the winter.

However, a potentially much more destructive form of ice falls from the sky every year, mainly during the warmer months, known as hail. Hail forms very differently than any other form of icy precipitation.

So just how can hail form during days when high temperatures reach well into the 80s or higher? The answer may surprise many.

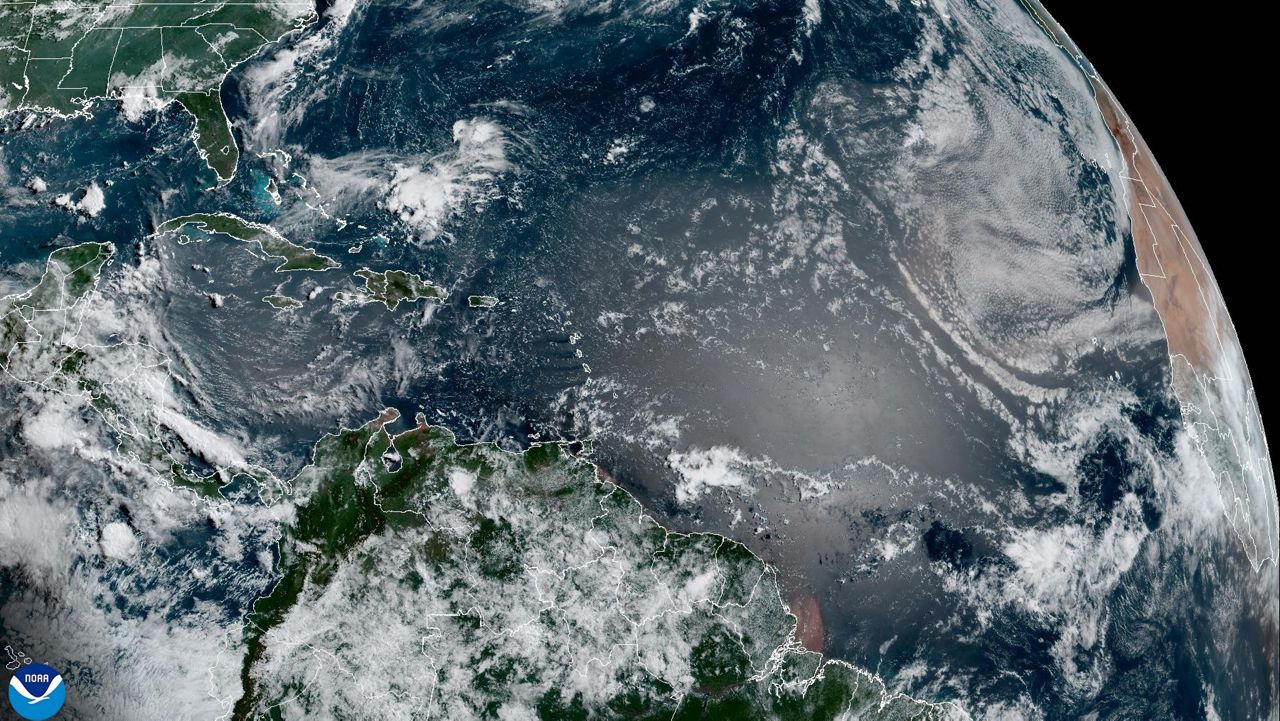

Hail season is generally during the warmer months when thunderstorms develop. Thunderstorms feed off of warm, unstable air that is often present during spring and summer as well as autumn in this part of the country.

While the air may be well above freezing at the surface, that is not the case thousands of feet aloft. As a thunderhead towers higher into the atmosphere, it eventually reaches the freezing level.

Generally, the atmosphere gets progressively colder at higher altitudes, which is why most of the time it’s colder up in a mountainous region.

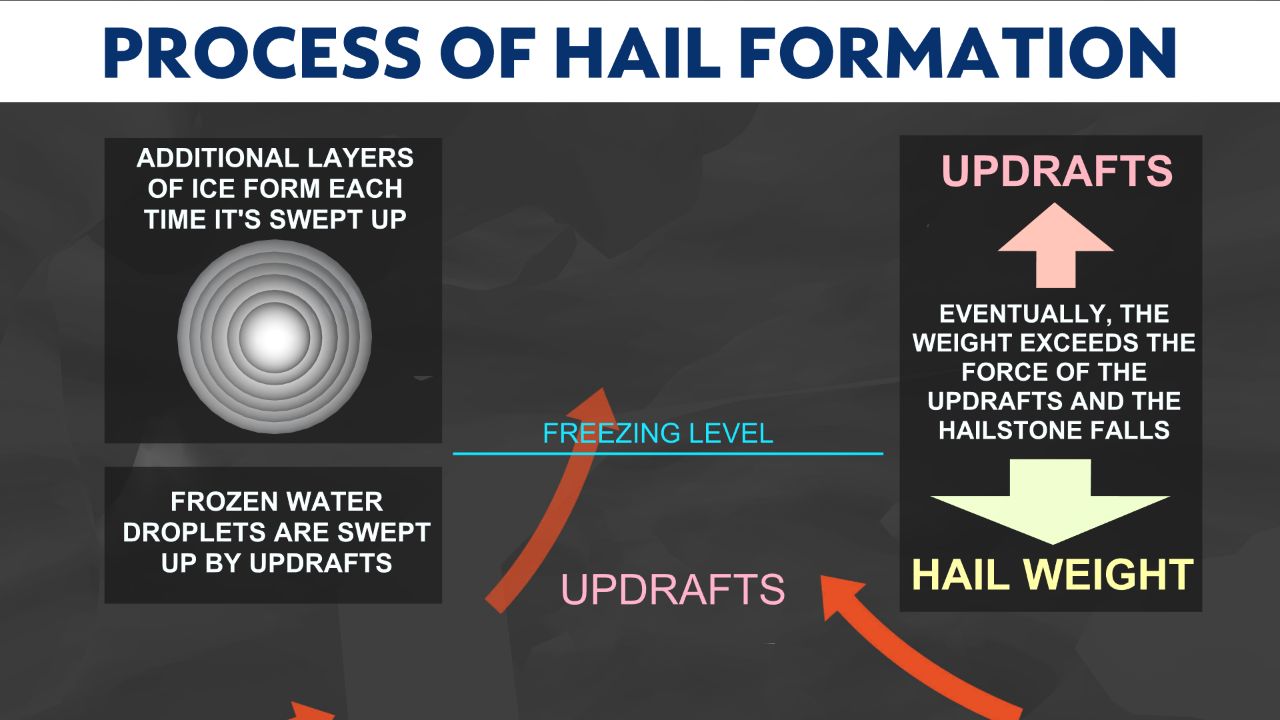

Within the storm, there are different regions where winds rush up into the storm (updraft) and accelerate towards the ground (downdraft).

Raindrops inside the storm are carried along with the wind currents. When conditions are favorable for it, those raindrops can be carried up into the mid to upper portions of the storm, where the air is below freezing.

Naturally, the raindrop will freeze and eventually fall back down below the freezing level. As this small ice pellet collides with other raindrops, it accumulates an outer layer of liquid water.

The ice pellet can often get recaptured in the updraft again and again, getting thrust into the upper reaches of the storm each trip up while also adding outer layers of water freeze.

This cycle can happen over many trips through the storm. Each time, the hailstone grows larger and larger.

Finally, when the updraft can no longer support the weight of the hailstone, it falls to the ground.

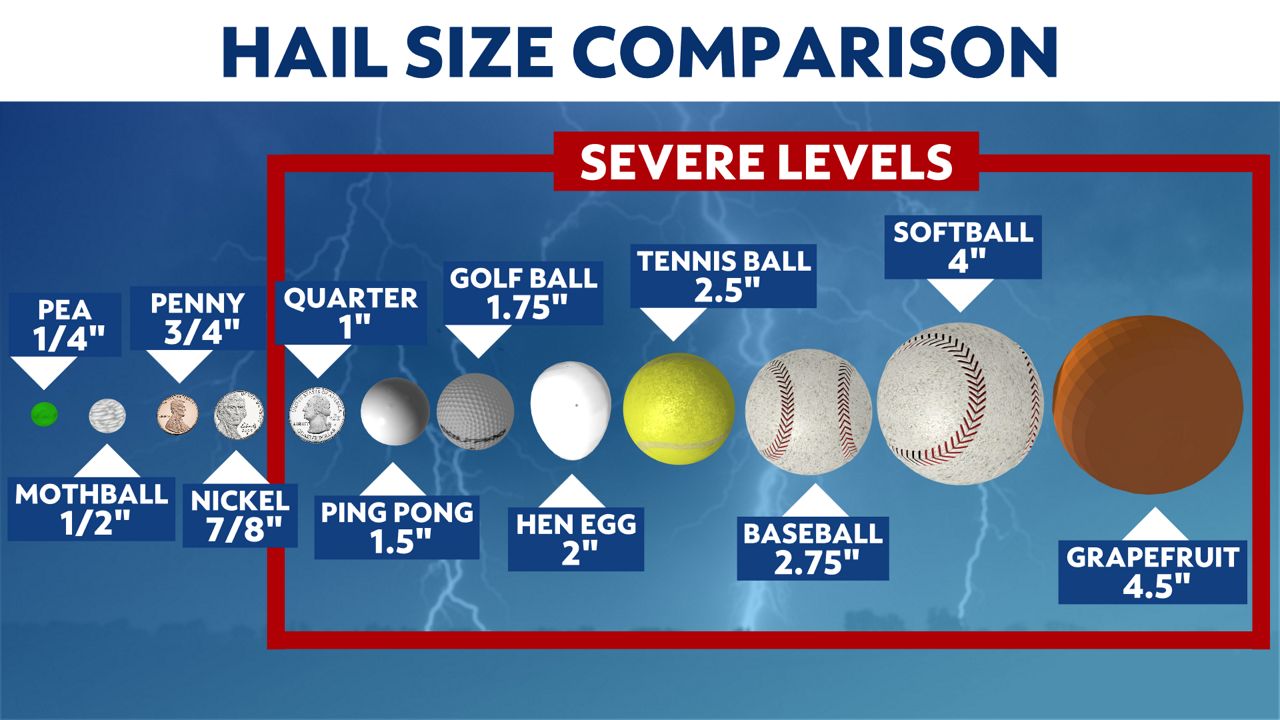

What’s astonishing is how large a hailstone can get! One has to marvel at the force of the wind speeds within a severe storm that are able to suspend such a large hunk of ice.

What’s equally impressive is the amount of hail that can fall from a storm. A mid-summer afternoon can be transformed into a “winter wonderland” with inches of hail covering the ground!

Here is a size chart showing how meteorologist categorize hailstones by comparing their size to objects people can relate to.

Above is a giant hailstone that fell near Hondo, Texas.

Large hail is responsible for damage to property and crops every year. In fact, according to NOAA’s severe storms database, over 4600 major hailstorms occurred in the United States last year.

And the damage caused was an astonishing $8 billion to $14 billion!

That could be the reason why a song was never written and recorded titled: “Let it Hail!”