GREENSBORO, N.C. — A national tour stopped by one of North Carolina’s graveyards that dates back to the 1800s, teaching volunteers how to preserve and restore these final resting places.

What You Need To Know

- Greensboro was the only stop on the 48State Tour- Saving America's Graveyards, a national tour teaching gravestone preservation and restoration

- David Craft is a Volunteer with the Friends of Green Hill Cemetery, giving historical and botanic tours and preserving the graves

- There is a proper way to clean and preserve the graves and if not followed correctly could damage them

- Green Hill Cemetery is the city's oldest graveyard with around 19,000 plots dating back to the 1800s

Green Hill Cemetery is Greensboro’s oldest and most historic operated cemetery. It sits on 51 acres, with around 19,000 plots. It contains family plots and notable individuals, including the city’s inaugural mayor.

With this many gravestones and memories, the city and Friends of Green Hill Cemetery, a nonprofit organization, is helping keep these legacies alive and polished. Including David Craft, a volunteer with the organization, who has spent years of his life in the cemetery.

“I'm very active. I like to something to do. I live nearby. This is like artwork. ... It's history,” Craft said.

His father, Bill, planted around 300 trees in the cemetery years ago and now Craft gives historical and botanic tours at the cemetery, along with preserving the stones.

“I started actually cleaning and straightening [the gravestones] ... after we went to this seminar in Statesville,” Craft said.

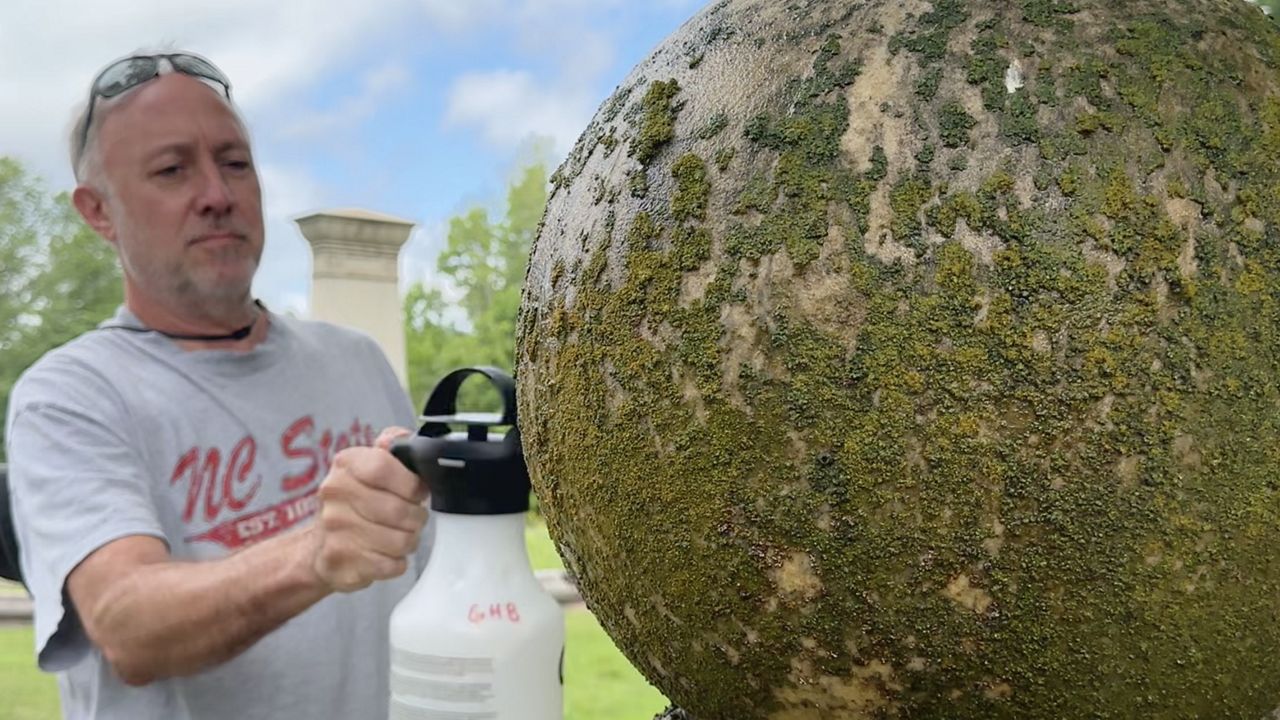

Starting his journey in the preservation hobby after attending the 48State Tour- Saving America’s Graveyards. This is a national tour run by Jonathan Appell, a gravestone conservationist, with Atlas Preservation, who is traveling to 48 states in about 48 days teaching volunteers how to clean, reconstruct, and level grave stones.

“I learned that this is serious work. You just can't go out and do this without getting some knowledge and training, like piecing stones together. I've seen it twice, but I'm still not ready to do it…you're you're working on somebody else's property, so you better make sure that you're doing it the right way,” Craft said.

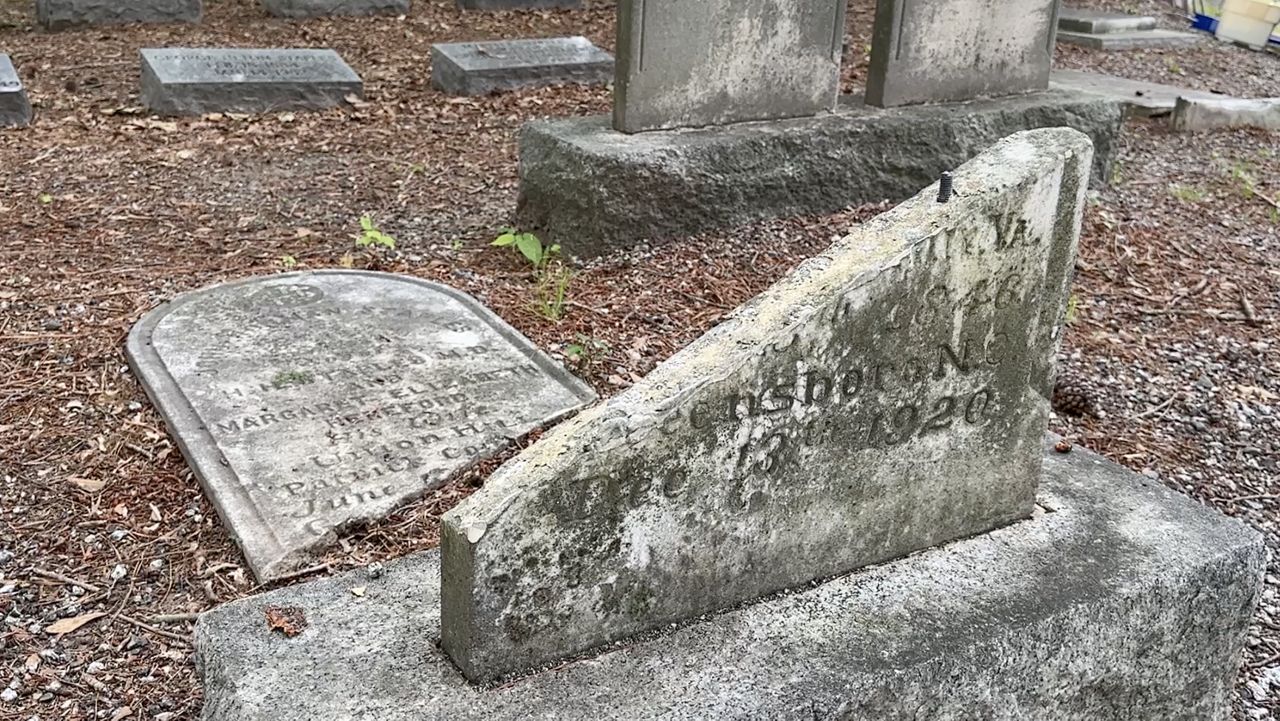

Craft submitted Green Hill Cemetery last year for the tour, which was selected as the only stop in N.C. As he says, hundreds of the gravestones are broken or could be cleaned at the site.

Dozens of volunteers from across the state, including other preservation and restoration groups, came to learn and better their abilities, with others just learning how to do it on their own.

As they scraped off years of lichen and algae, names from hundreds of years ago began to emerge, Craft’s favorite part, as he can look up their name on Find a Grave, which normally has a list of family members, the age at which they died, and possibly even news articles about their life or death.

Including the grave of a woman named Georgia S. Tucker Newell, who died in 1886, at the age of 27.

“I know a little bit more about her. I think anybody would be happy that somebody clean the grave, whether it's Georgia or Georgia's descendants of I mean, I think what we're doing is a good thing and generally people would appreciate it,” Craft said.

According to Craft, the Friends of Green Hill Cemetery make an effort to contact the families before working on their gravestones, especially for major reconstructions. However, there are often no family members left.

“We clean and straighten without permission because it's really hard to get permission if we're going to actually physically work on a stone like piece it together or raise it back up. We're going to try more, more intentionally to connect with the family, either to find a grave or a public notice on the city website or something. But again, a lot of these people, they've been gone from here 100 years, but hopefully we're doing the right thing and maybe they'll see it and hopefully they'll appreciate it,” Craft said.

Although, he says some stones are beautiful just the way they are.

Craft also cleans his parents' and other family members' gravestones at a nearby cemetery.