ROCKINGHAM, N.C. — The overdose epidemic has been costly, deadly and seemingly never-ending. One man affected by addiction is joining others on a continued road to recovery in Rockingham, North Carolina.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports more than one million deaths to drug overdose since 1999. The National Center for Health Statistics attributed more than 75% of the nearly 107,000 drug overdose deaths to an opioid in 2021. Finding help can be the difference between living and dying for people in the throes of drug addiction.

For nearly 50 years in Richmond County, there’s been one place people can turn to help them get clean: The Samaritan Colony.

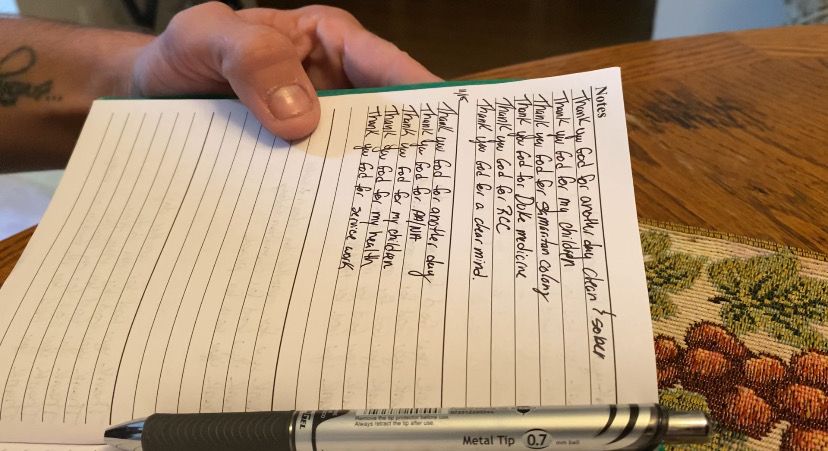

Peter Gaudiomonte has become used to the everyday fight for sobriety. That’s why he keeps a daily gratitude journal.

“It gives you that perspective, especially when you do it first thing when you wake up in the morning. It gets you in the mindset of looking for things to be grateful for,” Gaudiomonte said.

Practicing gratitude in this form is something Gaudiomonte learned to pick up during treatment for drug addiction at the colony. Gaudiomonte said when years of use fogged up his memory, he turned to the page.

“I started writing everything down that I do throughout the day,” Gaudiomonte said.

Gaudiomonte said he tried the colony, a 12-bed residential treatment facility in Rockingham, for the first time in 2016. It was the second effort at rehabilitation overall. In his first go at the colony, Peter lasted 28 days, the standard amount of time each person spends in the program.

Gaudiomonte estimated he stayed sober four months while going to Alcoholics Anonymous meetings after leaving the first stint. He said things took a wrong turn when he quit following the playbook of following up with a sponsor, going to AA meetings, writing down gratitude and continuing volunteerism in the community.

Meanwhile, Gaudiomonte, 35, believed his family relationships also broke down. The former postal service worker said he lost a job, eventually his marriage and part of his oldest son Liam’s childhood. He said they welcomed a second child, Killian, into their family in 2017. When Killian was 3 months old, Gaudiomonte said he still struggled with opioid abuse and realized a real change had to be made. Gaudiomonte confirmed he checked himself into the colony for a second time on December 13, 2017 through January 1, 2018.

Five years later, the graduate of the colony said the lessons learned in the second attempt at the residential treatment center are what saved his life. Gaudiomonte flipped open the pages of his journal.

“I’m basically just thanking God for another day,” Gaudiomonte said. “For AA and NA, my children, my health and service work.”

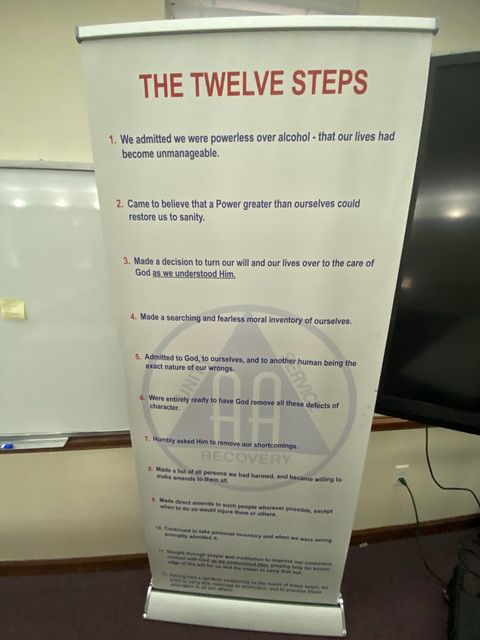

The next nine months of 2018 would be better as Gaudiomonte attended meetings for the first 90 days after successfully completing his final round of rehab at the colony. The 12-step-model of peer support taught in AA/NA helped him recover, achieve abstinence, introduced him to a more in-depth understanding of Christianity, developed healthy lifestyle choices and established a reliable way to approach drug addiction.

Beyond treating his substance use, Gaudiomonte said he was born with a kidney disease called IgA Nephropathy. He described it as a buildup of kidney tissue over time that can lead to serious damage to the organ. Given his baseline of health, Gaudiomonte said years of alcohol and drug use may be what jumpstarted a greater issue inside his body: kidney failure. Gaudiomonte said doctors can neither confirm nor deny substance use as the exact cause of his kidney failure. He woke up one morning with a blood pressure of 210/150 in October 2018. His kidneys shut down, and he ended up in the hospital on Halloween with Stage 5 kidney failure.

The next few years would be spent hooked up to dialysis machines, booking appointments at various medical offices, meeting doctors for secondary health issues potentially caused by kidney failure, such as why his heart couldn’t pump blood as well to the entire body, undergoing multiple cardiac surgeries and the 24/7 battle for sobriety.

“When I was on dialysis and had a lot of heart troubles, I wasn’t sure if I would have another day,” Gaudiomonte said. “I am definitely grateful I get to wake up every morning with a clear mind and healthy.”

Oddly enough, the kidney his body needed to live came from a person at the colony. Harold Pearson, the man credited with much of the colony’s sustained success, is the former executive director. When his daughter, Christi Pearson, heard about how Gaudiomonte was in need of a kidney, she volunteered her own.

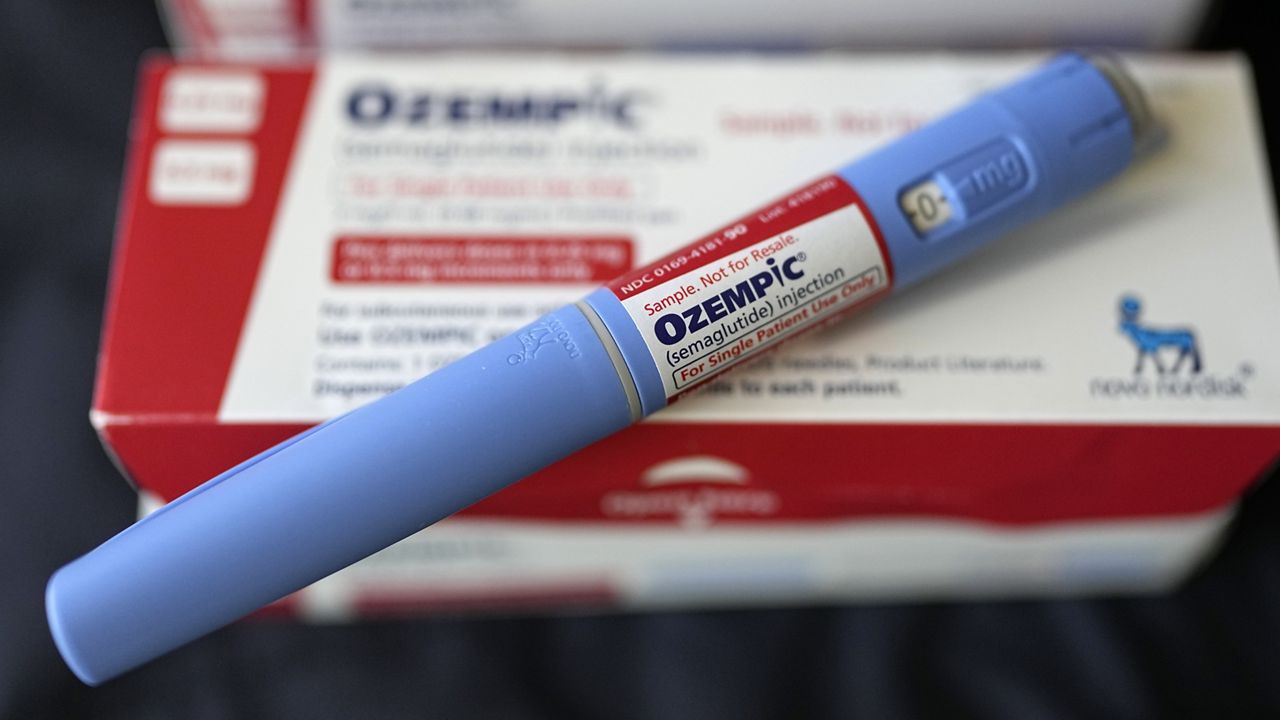

Gaudiomonte said he received the new kidney in August 2022. Since then, Gaudiomonte has grown accustomed to his meticulous pill regimen. Insuring the health of the kidney through modern pharmaceuticals is a reality he can’t expect.

The practice of choosing positivity every day and being accountable to himself are principles Gaudiomonte learned from Mark Christopher at the Samaritan Colony.

“What we learn to do here is inventory ourselves,” Christopher said.

Christopher should know. The former resident said he entered the walls of the colony to treat his addiction more than 12 years ago and never left.

“It's been advantageous for me because you deal with different personalities and really that's what you're having to do in treatment,” Christopher said.

With a professional background working in management at a manufacturing facility, he saw an opportunity to use his life for a bigger purpose as a paid staff member.

“[You have to] figure out how to approach a person. Some people need approaches [that] are kind of rough, some people just can't take it. You have to deal with it. So it's really about figuring out the individual and how to impact that individual,” Christopher said.

The 12 men enrolled in the program, like Gaudiomonte at one time, learn by doing.

Christopher goes by Mark C. to the men in this room as a nod to the way people address others and reference themselves in AA/NA meetings.

Most days at the colony are predictable. Lunch starts on time at noon Monday-Friday in the mess hall. Christopher said residents funnel into the dining room for a roughly 10-15 minute meal. Once every man eats all his food, they go right into cleanup.

Everyone adheres to schedules, promptly finishes chores — like washing dishes and putting food away — then doing it all over again the next day for all 28 days they live at the colony. It’s a no-nonsense approach Christopher knows all too well as a graduate of the program, who became the executive director at the beginning of this year. He's seen much more than food and fellowship served in this dining hall.

“What we are giving them is some tasks to do that they are capable of doing that they don’t necessarily want to do, or like to do, or think they need to do because they are going to have all of those thoughts when they leave treatment about the actions to treat the disease of addiction or alcoholism,” Christopher said.

As a person who fought hard to overcome substance use, Christopher said every man who joined the program has to ask themselves a serious question: Am I ready to start living life sober by replacing older, destructive habits with newer, healthier ones? The catch is the big change anyone seeking sobriety must understand is the behavioral makeover doesn’t happen overnight and requires a true day-to-day commitment.

“Most people try to think their way out. You can't think your way out. You have to behave your way out,” Christopher said.

Being a leader of the treatment facility means leading men down the path to staying clean. Cell phones of any kind are not allowed in the quarters nor anywhere else in the building. Shaving, making a bed and following a dress code are all requirements.

So is taking serious inventory of what landed them in the facility. Those possibilities are routinely a conversation piece in the colony’s 12-step meetings patterned after alcoholics and narcotics anonymous group settings with men who could arguably walk a mile in each other’s shoes.

To join their circle is to try to escape the clutches of addiction by reshaping three areas of life: physical, mental and spiritual.

“What they need to understand, if you're here, there's another bottom. Hmm. And it's whether you experience or not, it will be based on what you do. But it's there because you're not dead,” Christopher said. “We've made it a family disease. I believe that we make our entire family sick.”

Christopher, 57, said he felt like he affected his wife and two sons with his reliance on drugs and alcohol.

“Gradually worked its way to the top of my value system. It inverted my values. And then I was making all my decisions based on that,” the executive director said.

He said somewhere between 144 to 160 men complete the program every year.

Christopher said his wife gave him an ultimatum when alcohol and painkillers took a chokehold on his life before allowing him to live with their family again in 2011.

“You are not coming back here until you get some help,” Christopher said.

He took his wife’s words to heart and entered rehab at the colony.

His new office is down the hall from the four rooms where current residents live. Each living space is numbered at the top of the bedroom door 1-4. Christopher walked into one of the four and flipped on the light to the room he said saved his marriage, life and relationship with his two sons.

“Room 4. This is my bed. This is where I spent my nights in treatment,” Christopher said.

The self-described former addict said faith is a cornerstone of his recovery along with being foundational to their mission of ending chemical dependency on drugs and alcohol.

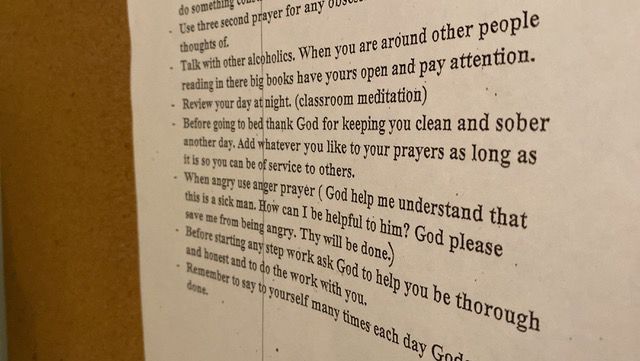

Christopher pointed to a paper tacked on the wall of his former room.

“These are all spiritual tools,” Christopher said. One sentence read, "think before you speak to make sure you are not telling lies," as a pledge to be honest with yourself and anyone else.

“It’s really good for somebody who just came in, like stop and pray, don’t quit,” Christopher said.

Learning to not give up is something many in the recovery community celebrate yearly. The final date of substance use is known to the recovery community as a "sober birthday."

The gift of sobriety is celebrated by Christopher too. He doesn’t keep his breakthroughs a secret. Instead, he documented them above his old work desk.

“Every posted note you see on this wall was when I was sitting at my desk doing meditation before work,” Christopher said.

How addiction affected his life and others is something Christopher pondered greatly after he joined the staff at the colony full-time.

These sticky note epiphanies represent his mental transition from being a patient to being on the Samaritan Colony payroll.

“There’s one up here that says, ‘It’s in the shelter of each other that we live.’ That is exactly what they are learning to do here. Live in the shelter of each other,” Christopher said.

The wall also conjured up one painful realization that hit him like a ton of bricks on the morning of July 11, 2011: A date he called the day of his awakening.

“That happened to me while I was in treatment when I woke up and said, ‘Man, my life's passing me by. I’m killing my boys.’ That’s when I made a decision to do whatever I was told,” Christopher said.

From one father of two boys to another, the leader of the colony gave his understudy, Gaudiomonte, the same advice: Do what you are asked to do if you want to stay sober, form a relationship with your children and to stay alive.

The suggestion isn’t lost on Gaudiomonte. As Gaudiomonte flipped through the paper envelopes of old pictures, he fixated on photos of him with his sons Killian and Liam. He said their love got him through kidney dialysis and keeps him clean.

Peter Gaudiomonte said he is in the Ticket to Work, a Social Security career development program for people who receive disability benefits and want to work. Through Ticket to Work, Gaudiomonte said he was connected with a state-run vocational rehabilitation agency to hopefully find gainful employment down the road. He said the goal is to see if his body is capable of handling a 40-hour-a-week workload with a new kidney, as he earns money from odd jobs and electrical work to get by.

Guadiomonte said he is taking classes at a local community college and is living with a family relative as he figures out his next step, while never missing an AA meeting.

There is plenty of reason for the colony to continue serving Richmond County and the surrounding rural areas often plagued by opioid addiction. The Drug Enforcement Agency tested for fentanyl in opioids seized throughout the country. The nation’s top drug enforcers discovered “7 out of 10 fentanyl-laced counterfeit pills contained a potentially lethal dose of fentanyl” in 2023.

The North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services reported more than 11 people died from drug overdoses every day in 2021.

As if statistics alone didn’t provide enough motivation, the colony will soon expand its mission to include women. Construction on a 13,000-square-foot women’s only facility began in 2022. The separate 14-bed treatment center will offer similar services to women diagnosed with substance use disorder as the flagship program does for men.

Development Director Maggie Sergio said nothing is possible if outside money doesn’t filter in. Sergio came on board in 2020 to help with the opening of the Women’s Center at the Samaritan Colony.

Years of experience of the Silicon Valley technology industry taught Sergio a targeted approach would work best. Under the banner of "A Changing Lives Campaign," Sergio helped the colony craft a gameplan for raising money for this new shelter as the chief cultivator of their donor base.

“[My idea was] let’s put a structured fundraising campaign into place,” Sergio said. So they did.

The State Employees Credit Union donated $1 million to the colony’s building efforts and operational expenses toward the women’s shelter. The Samaritan Colony doesn’t turn away anyone because of a lack of money. Sergio said they don’t take insurance, but they offer room and board based on a sliding payment scale.

Fundraisers can be family members, organizations, churches and members of local communities.

Christopher said because the colony is a nonprofit organization, it relies solely on the goodwill of others to fund a little more than $500,000 a year budget.

“Now, if you think about that, we are housing these men, we are feeding these men, we are providing them with one-on-one counseling, two lectures a day, group meetings, [and] transportation. We do all of that for just over $500,000 a year — including everyone’s salaries, food, everything. Samaritan Colony through the years has learned how to make a dollar go a long way,” Christopher said.

The completion of the women’s center is estimated to be mid-2024 with a total project cost of close to $4 million.

Turning dollars into dreams is why Christopher has stuck around.

“That's really what we do with people every day. We take something that's destroying them. We teach them how to use it to their advantage to learn from it. They'll be better men than they've ever been before,” Christopher said. “And that's what we're going to do with women, too.”