NEW BERN, N.C. — Sarah Boone, formerly Sarah Marshall, was born into slavery in Craven County in 1832.

What You Need To Know

- Sarah Boone was one of the first black women to receive a patent

- She was born in Craven County in 1832

- Historians at the New Bern Historical Society have been doing research on Boone’s life

- They say finding information on former slaves during the Civil Rights Era is difficult because many stories were left untold

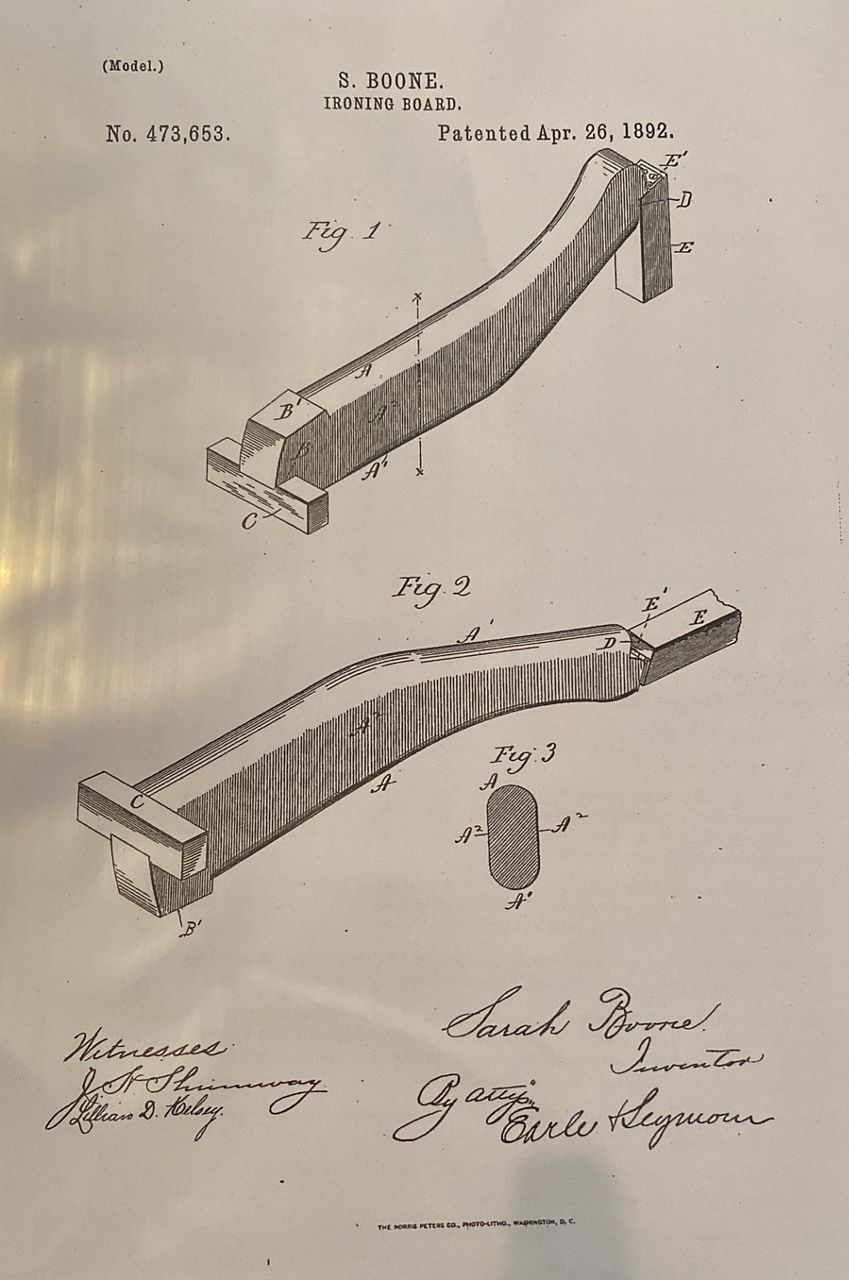

She married James Boone, a free Black man, in 1847. Historians speculate that her husband bought her freedom, and they followed the Underground Railroad to Connecticut before the Civil War. There, she learned how to read and write and became a dressmaker. After she re-invented the ironing board, Boone became one of the first Black women to get a patent.

While some of Boone’s story has been confirmed through documents, a lot of information about her is speculated, and there’s no proper way to confirm the guesses. In fact, the photos that come up online are most likely not of Boone.

However, the research has to start somewhere. In New Bern, it starts with Claudia Houston, a historian at the New Bern Historical Society.

“I have always loved American history,” Houston said. “I don’t know why. Like why do you like anything? I just have always loved American history.”

Although Houston is from New York, ever since moving to New Bern 15 years ago she’s buried herself in its history. Five years ago, a reporter from Connecticut reached out to Houston to ask about Boone, the former slave from North Carolina. Houston immediately dove into the story of the patented pioneer.

“[Boone] literally took the old ironing board, which was basically... a board on the two chairs, and you’d have your iron,” Houston said. “It just didn’t work. And Sarah decided there was a better way to do this.”

Having never heard of Boone before then, Houston went to her team for help. Jim Hodges is the curator of collections at the New Bern Historical Society. His office is the first place Houston goes when she’s looking for information on a new research project.

Hodges grew up in New Bern and has been volunteering at the historical society for the past 10 years. He’s been immersed in the history of New Bern for years. When Houston came to him asking for information about Boone, their search came up empty. It’s a problem Houston has faced with many projects about local African Americans.

“We’re still trying to say, ‘OK, we need to tell the story of the Black community cause it’s our history,’” Houston said. “It’s not that it’s not our history, but we didn’t know about it either.”

New Bern was very segregated during the Civil Rights Era, and many contributions went without recognition. Many stories like Boone’s were lost or very difficult to find.

“I mean, I’ll publish stories about African Americans, and people are like, ‘I had no idea,’” Houston said. “Well, no one did because they weren’t allowed to tell their story. We’re trying to close that gap and get more information and put it out there for everybody to read because a lot of people in the community don’t know their own stories either.”

Despite the challenges, Houston is determined to find whatever information she can and share it with the community.

“We really can’t forget history,” Houston said. “We have good, bad and ugly. We have a lot of ugly, unfortunately. But we can change it if we look at what happened. Why did it happen like this? And we want to make sure that doesn’t happen again. And who were the people who persevered? Who were the people that came out of this and did some amazing things?”

Boone spent the rest of her life in Connecticut where she had eight children. She died in 1904 and is buried in New Haven.