WILMINGTON, N.C. — After years of hard work to develop a targeted cancer treatment, two University of North Carolina Wilmington professors and their team of students are finally getting results that make it all worth it.

What You Need To Know

- University of North Carolina Wilmington students and professors have spent the last 12-15 years working on a targeted treatment concept for breast cancer

- The principle is now transferable to other cancer variants

- The compound will undergo animal trials before advancing to the medical field

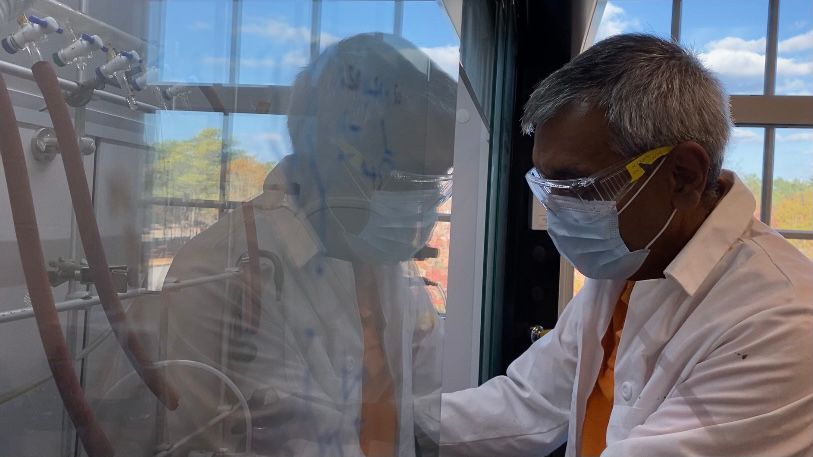

Dr. Sridhar Varadarajan, a chemistry professor at UNCW, became interested in cancer research over a decade ago when he realized he had the skill set and tools at his disposal to potentially revolutionize current cancer treatments.

“Unfortunately we have some normal cells that behave like cancer cells,” Varadarajan said. “All these cells succumb to this treatment. The drug is damaging their DNA, they're not able to fix it and they die.”

Chemotherapy approaches currently attack every cell in the body, which can have side effects including mutations and secondary cancer, but the molecule Varadaraja's working to develop at UNCW is capable of targeting specific cancer cells.

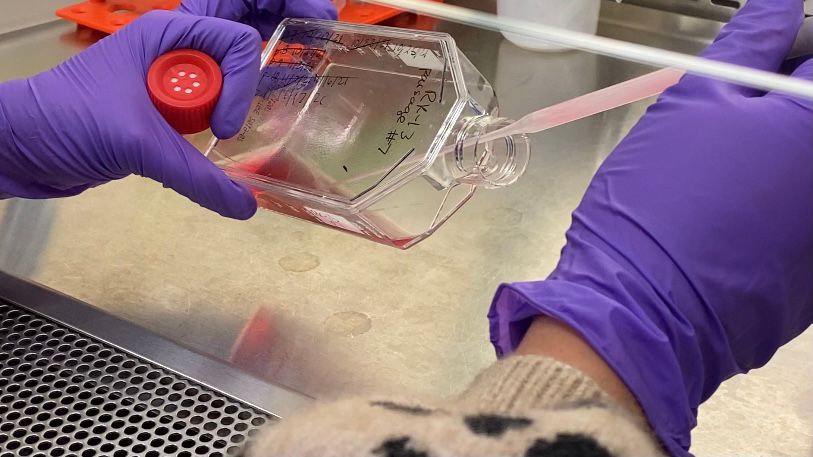

“We bought compounds, we attach it together, make a special kind of DNA-damaging molecule,” Varadarajan said. “It damages the DNA at very particular locations, and that kind of damage is very toxic to the cell but it won't lead to mutations.”

Varadarajan and his students can only take the research as far as development. When it came time to test their compound, they required the assistance of fellow professor Dr. Art Frampton in the biology department.

“So they're the ones that generate the compounds and then he brings those compounds down to our lab and we actually test them on the various cancer cells,” Frampton said.

Both professors actually find themselves at their desks more often than in the lab as their students conduct the bulk of the research. Varadarajan said that's exactly how it should be, and Frampton adds that this is an opportunity many students wouldn't get the chance to experience if this research were being conducted at a larger university.

“The students here are just amazing,” Varadarajan said. “They're so excited about learning and doing this stuff and we couldn't do it without them. Between the biology and the chemistry department, we have everything that we would need to conduct this high level research.”

“The way that he teaches and the way that he talks about his research is just really inspiring,” Caprice McNeely, one of Varadarajan's graduate students, said. “The second you sit down and hear him start to talk about the way that they designed these drugs and the way that they took all these different problems and then found a way to solve each of them - it got me so excited.”

They first started working on a treatment for breast cancer and have since moved on to prostate cancer. Now that they've developed the base molecule, in theory they can switch out which receptor the compound will bind to, allowing the treatment to be applicable to multiple kinds of cancers.

“It's more of a scalpel type approach versus a sledgehammer type approach for chemotherapy,” Frampton said.