CHARLOTTE, N.C. — In the last several months city leaders have been discussing a big policy document. It’s their 2040 comprehensive plan, which could impact housing density and what neighborhoods look like. It also talks about the racial inequities that have happened in Charlotte’s housing history.

Well-known Writer Mary Curtis hosts her own podcast. She says it looks at policy and politics through the lens of social justice. It is a topic she has covered extensively in her 30-year career. She has held jobs with the Washington Post, New York Times and others.

“In order to understand what is going on today we have to understand our history,” Curtis said.

The history isn’t always pretty. Curtis said she moved to Myers Park in the 1990s. It’s a part of Charlotte known for its beloved willow oak trees, good schools and high-end homes.

“If I hadn’t moved to Charlotte from the New York area, where housing was much more expensive, and I was able to sell my home and put a down payment on this, I could never have moved into this neighborhood,” Curtis said.

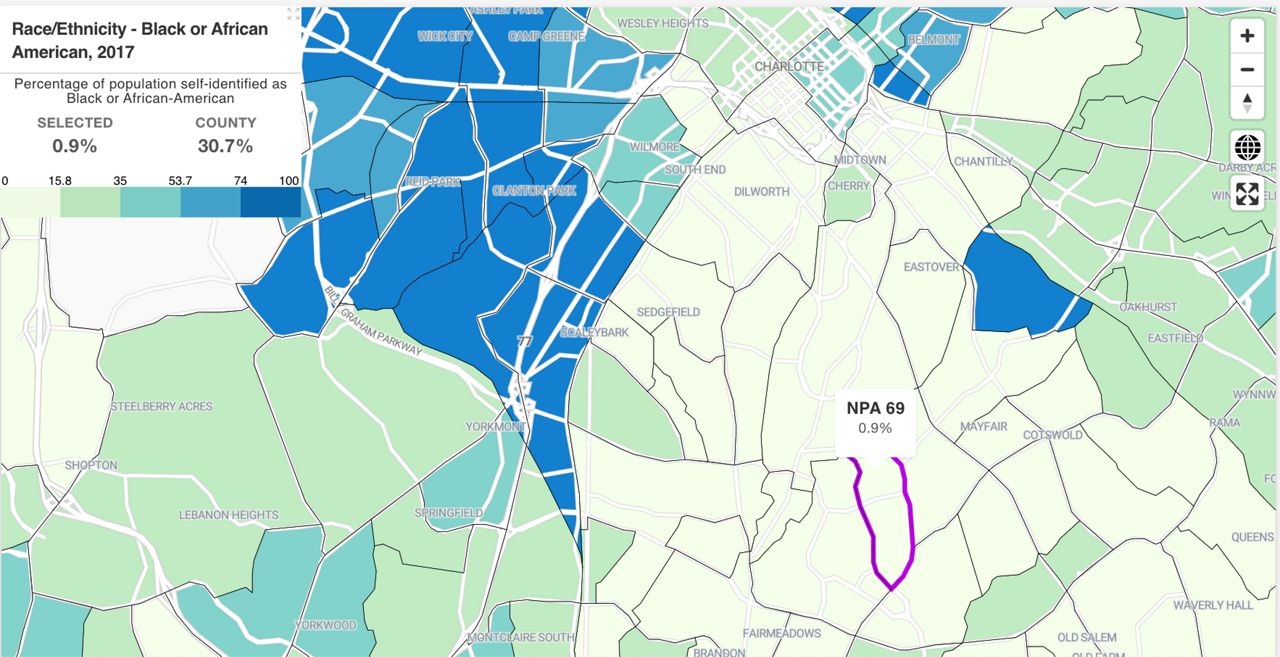

Curtis and her family were among the first Black families to move to Myers Park. According to UNC Charlotte Urban Institute’s most recent data on demographics in 2017, her neighborhood was less than 1% black.

Historian Tom Hatchett explains her neighborhood was segregated back in the early 1900s. Jim Crow laws prevented Black families from moving to certain neighborhoods, and the Myers Park area was one of them.

“What has happened is we have layered laws and regulations on top of each other, beginning around 1900 with restrictive covenants and deeds,” Hatchett said.

Those deeds had language that said “white’s only” or “no person of the colored race.” Curtis read one from 1939.

“Wow, that is intense to see this,” Curtis said. “That is emotional too. Think of the drama.”

Not only were Black families shut out of certain neighborhoods, but Hatchett explains they were also denied homeownership. That is because of redlining. In the 1930s, the federal government mapped out what areas they deemed to be good credit risk and areas deemed they deemed bad. It prevented certain families from getting a home loan.

“The bad risk was any neighborhoods that had Black people in them,” Hatchett said.

Many laws have changed since that time. The racial language in deeds was ruled unenforceable by the Supreme Court in 1948. But it wasn’t until 20 years later that it became illegal to put racist language in new deeds. This was thanks to the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which also made it against the law to deny a home loan based on race.

Hatchett explains since Black families were denied home loans in the early 1900s they had missed out on generations of home equity.

“This all ties into the wealth gap,” Hatchatt said. “My dad was able to get a FHA loan in the 1930s, and I was able to buy my home because my dad helped me with the down payment and he owned his own house. If he had been on the wrong side of the racial hierarchy I am not sure if I would own my own home.”

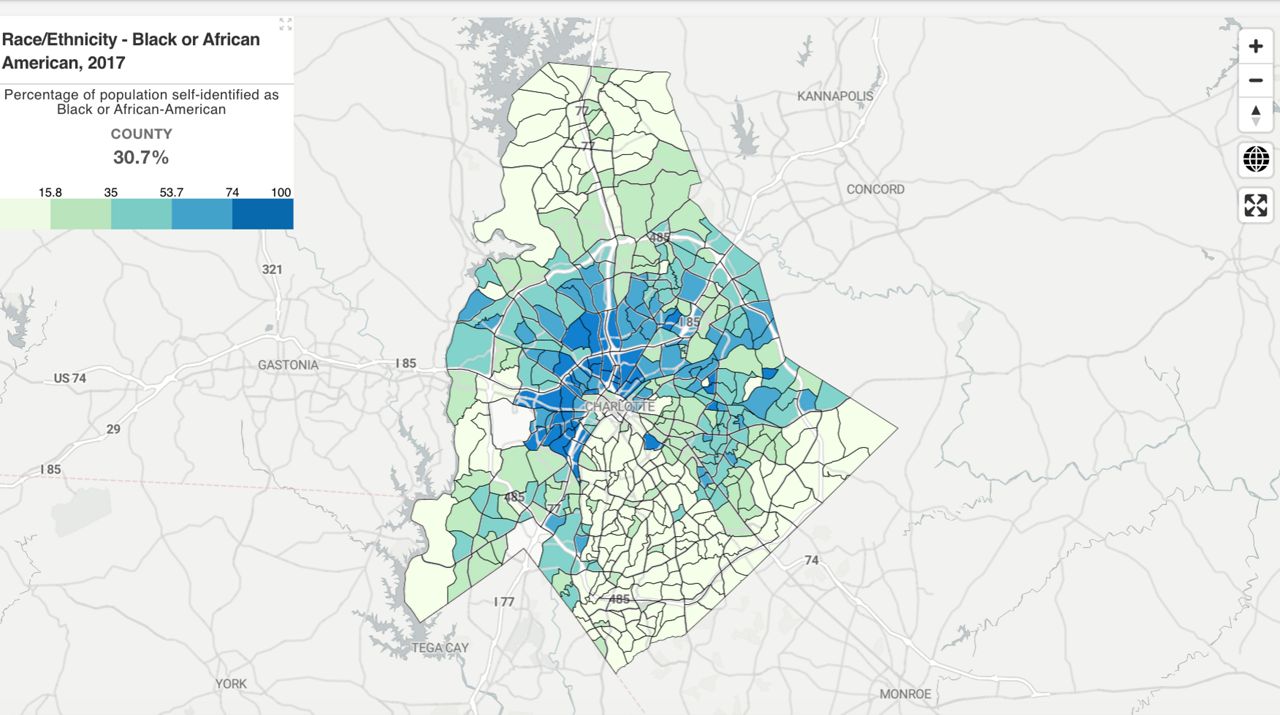

Ely Portillo is the assistant director of outreach at UNC Charlotte Urban Institute. The department has created maps that show the demographics of where people live, household income and more. Their most recent maps from 2017 show that most black families live in west and north Charlotte. This area also has the lowest household income, at around $32,000, the lowest percentage of homeownership at about 30%, and the lowest number of people who have gotten a Bachelor’s degree, which is about 12%.

“This represents the historical patterns of residential segregation that we have seen in Charlotte,” Portillo said.

Portillo said the redlining map from 1935 doesn’t look much differently from maps today. The areas green and blue are still 90% white. Many of the areas in red and yellow are predominately Black.

“The momentum of history in older areas is unfortunately still with us,” Hatchett said.

According to the U.S. census bureau homeownership for white people today is around 70%, whereas for Black families it’s about 40%.

“White people had a big head start in settling these areas, and it has made it much more difficult for a Black person to settle in,” Curtis said.

It’s why she thinks it’s important for people to understand the history of housing in Charlotte.

“Are we just going to throw our hands up and say, well nothing we can do about it now or are we going to try and do something to make it better,” Curtis said.