TEXAS — When Nadia Kerr joined a program for incarcerated mothers a year into her 20-year prison sentence, she hoped it would help her maintain some kind of relationship with her two daughters while she did her time.

At first, the visitations with her daughters, organized by Girls Embracing Mothers, a Dallas-based nonprofit, kept Kerr out of trouble in the Hilltop Unit Prison for Women in Gatesville, Texas.

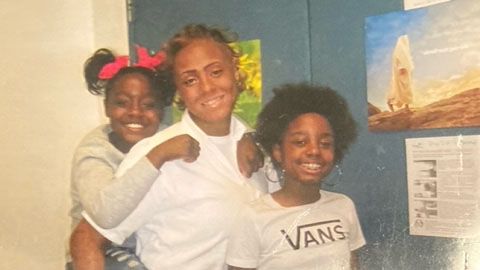

The visits allowed Kerr to hug and to talk with her daughters, Meghan, then 7, and Aaryn, then 4. During the four-hour visits, they shared lunch and Kerr brushed and braided their hair. They did art therapy sessions together that inevitably ended in keepsake artwork by the girls to decorate Kerr’s cell walls.

“It was amazing,” Kerr said. The program helped the 25-year-old, convicted of armed robbery with a deadly weapon, settle down in her unit, where she was prone to angry flare-ups.

But a few months into the Girls Embracing Mothers program, Kerr found herself slipping back into her old ways, causing problems behind bars that resulted in her suspension from the program for several months.

The visitations with her daughters ended, dashing Kerr’s hope of her girls seeing her as their mother.

It was Kerr’s oldest daughter, Meghan, who got Kerr back on track when she was allowed to see her mother again.

“Meghan kind of looked at me differently,” Kerr said. “She told me, ‘Don't get in trouble no more.’ So, I didn't. I straightened up real quick.”

The number of incarcerated women in the United States has increased by more than 750% since 1980, according to The Sentencing Project’s analysis of Bureau of Justice Statistics.

With the number of women admitted to prison rising in the U.S., so, too, are the number of minor children being left behind.

About 684,500 state and federal prisoners were parents of at least one minor child in 2016, according to a report released last month by the Bureau of Justice Statistics. In both state and federal prisons, 58% of incarcerated women were mothers of at least one minor child, compared with 47% of incarcerated men, the report said.

The study found that an estimated 1.5 million children 17 years old or younger had a parent in a state or federal prison in 2016, the latest year reported. A 2015 report from Child Trends estimated that at least 7% of children in the United States had had a parent incarcerated at some point when they were minors.

“Parental incarceration, whether it's a mother or a father, is considered an adverse childhood experience,” said Dr. Jillian Turanovic, an associate professor in the college of criminology and criminal justice at Florida State University. “It can be a form of trauma for children to have their parent removed from the home. It could be traumatic for them if they witnessed the arrest itself.”

Children of incarcerated parents were more likely to face psychological strain, antisocial behavior, suspension or expulsion from school, economic hardship, and criminal activity, according to a 2017 study published in the National Institute for Justice Journal.

The study noted that a strong parent-child bond and the quality of the child and family's social support system “play significant roles in the child's ability to overcome challenges and succeed in life.”

In Texas, the nongovernmental organization Girls Embracing Mothers, or GEM, works closely with the state prison system to provide monthly four-hour visits with participating women and their daughters.

Brittany Barnett started GEM nine years ago with the first group of incarcerated mothers, including Kerr. Every first Saturday of the month, the daughters of the imprisoned women from the Dallas-Fort Worth area got on a bus to make the 2.5-hour drive to the women's prison in Gatesville.

The mothers and daughters would spend four hours in the prison complex’s educational building talking, sharing lunch, playing games and participating in art therapy and other programming.

The setting was more intimate than the general visitation rooms in state prisons, where visitors are typically allowed only two hours.

“I had a traumatic experience when I first went to visit my mother in jail, and I thought I was going to get to hug her and touch her and smell her and I couldn't, because she hadn't been in prison for 60 days, so I had to visit her through the glass and that was a lot,” Barnett said. “My mother's incarceration was devastating, even though I was 22 at the time. I can't imagine being nine or 10.”

The pandemic has severely curtailed the program’s activities as state prisons suspended all visitations to prevent the spread of COVID-19. This meant the GEM mothers and daughters were left communicating through letters and photos.

Besides the visitations, GEM provides group activities and a summer camp for the daughters, designed to empower girls who have mothers in prison or recently released “to break the cycle of incarceration and lead successful lives with vision and purpose,” Barnett said.

While not yet prevalent across the U.S., programs like Girls Embracing Mothers are popping up in other states as more evidence emerges surrounding the adverse impact on the children of the incarcerated.

Disproportionately, the children who are experiencing parental incarceration, either a mother or a father, come from communities that tend to be economically disadvantaged and made up of marginalized communities, and where over-policing is common and there is a lack of programming or social services to support and foster healthy development, Turanovic said.

Children may also face the stigma and the shame that comes along with having a parent in prison, Turanovic said. “Programming that can connect them to others who are having this similar experience can be really supportive and beneficial for children,” she said.

Meghan and Aaryn Kerr, Nadia Kerr’s daughters, both said the friendships they made in the GEM program were invaluable.

Meghan Kerr, now 15, said it’s not that she and her friends talk a lot about the fact that their mothers were in prison. But just knowing that everyone was going through something similar made it easier to just talk about “regular girl stuff,” she said.

Programs specifically geared to supporting women who are or have served in prison have been slower to develop in the U.S., Turanovic said.

Part of this may be attributed to the fact that while the increase in female prisoners has grown seven-fold since 1980, there are still significantly fewer women in prison compared with the number of men in the U.S. system.

“Most prison systems are built with men in mind, so I think there's always more of a need for gender-responsive programs developed for women and their unique needs,”“Most prison systems are built with men in mind, so I think there's always more of a need for gender-responsive programs developed for women and their unique needs,” she said.

Studies have shown that many women who are in prison have histories of physical or sexual abuse and may suffer mental health problems and other issues with trauma stemming from those experiences.

“We see in the research that histories of trauma and mental health problems and addiction issues are overrepresented among women in prison,” she said. “All of these issues are wrapped into how you address incarcerated motherhood and what this means for the family.”

Once released, many women face “renegotiating their identity as a mother” while balancing the often stringent conditions of release, such as routine check-ins with parole officers, she said.

Kerr made parole in February after completing an exit program for prisoners with addiction issues. Things are slowly falling into place. She’s found a job at Starbucks that accommodates her parole obligations. She’s found an apartment in Fort Worth she hopes to move into this month. Her ankle monitor is scheduled to be removed this month, too.

Right now, she and her sister and mother are sharing child-raising duties for her two girls and her sister’s daughter, a situation she looks forward to changing once she can move her girls in with her in the new place.

As grateful as she is for her mother taking care of her daughters during her 10 years behind bars, Kerr wants to be her girls’ full-time parent now.

“My 15-year-old is every bit of 15 years old now,” she said of her eldest. “I believe she is testing the waters, just to see where she can go. But it's also hard for her not living with me for me to instill me.”

There were times in the visits when Kerr would ask her girls, "Do you hate me? Are you mad at me?"There were times in the visits when Kerr would ask her girls, "Do you hate me? Are you mad at me?" and for a long time, their answers were “no,” Kerr said.

A few years into her sentence, Meghan finally opened up to her mother and said that yes, sometimes she was mad at Kerr for the situation.

“I just have to take that,” she said.

Kerr said that while participating in GEM, her girls got a “lesson in reality, a lesson in the stakes in life.”

While she was incarcerated, she said she didn’t sugarcoat how she talked to the girls about what her life was like behind bars. She told them about the strip searches she endured before and after each of their visits and the day-to-day challenges of prison life.

“I tried to speak to them as honestly and sometimes brutally as possible,” she said.

“They also got a lesson in transformation and metamorphosis. They saw me grow while I watched them grow,” she said.

This summer, Meghan and Aaryn will participate in the GEM summer camp held in the Hill County. Nadia Kerr will continue to work with the mother’s groups in monthly meetups and other activities.

Like any mother, she worries about them. In particular, she’s worried about what statistics say about children of incarcerated parents and the rates of the children who end up in prison themselves.

"I do worry about that," she said, adding a long, heavy pause that seemed to carry the weight of her incarceration with it.

More than anything, she hopes her past won’t present itself in their future.