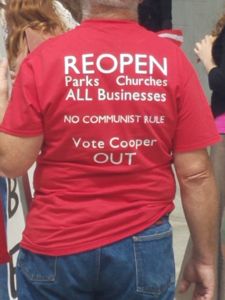

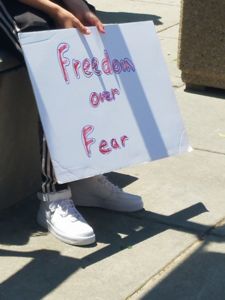

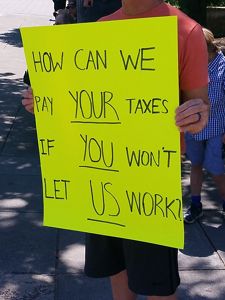

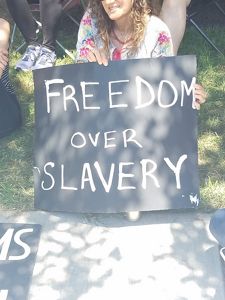

RALEIGH, N.C. — The third rally calling for North Carolina to reopen occured in downtown Raleigh on Tuesday.

More than 100 people are believed to have been in attendance, with a few counterprotesters present as well.

According to the North Carolina Department of Public Safety, four people were arrested near the end of the rally. Among them was the #ReOpenNC movement's co-founder, Ashley Smith.

Smith, a Morganton resident, was charged with violation of an executive order and resisting a public officer, according to authorities in Wake County.

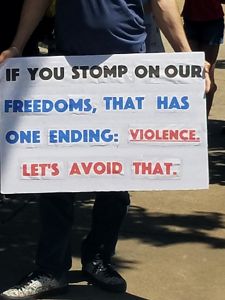

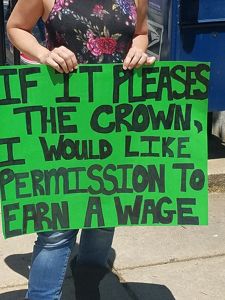

Those who participated say they’d like to see the state’s stay-at-home order lifted sooner, rather than later.

PODCAST: Coronavirus vs. the Constitution: Where do Rights End and Restrictions Begin?

Two legal experts on Monday said opponents to the state's stay-at-home order would have legal standing to sue but the case wouldn't be easy.

Late last week, an organizer wrote on the group's Facebook page that she was gathering information from businesses for a potential emergency injunction against the state. Co-founder Ashley Smith told Spectrum News she was not at liberty to comment on that.

UNC-Chapel Hill Prof. Bill Marshall said businesses are within their rights to sue over the state's stay-at-home order if they choose.

In order to have standing to ask for an injunction, Marshall said a plaintiff first must show there is a credible threat of enforcement and then demonstrate economic harm resulting from the order. According to him, those two tests would be easy.

However, what happens in front of the judge is another matter. Marshall said existing case law gives the state a fair amount of latitude when it comes to threats to public health. He said to expect lots of testimony from medical experts if any lawsuit goes to trial.

Another UNC law professor, Andy Hessick, said even at the injunction stage, the plaintiffs would have to prove Gov. Roy Cooper's move was unjust or illegal.

That would influence whether a judge agrees to issue a preliminary injunction to block further implementation of the order.

Hessick said even if the state can't provide legal grounds for its actions, it might still be able to justify them.