BEVERLY HILLS, Calif. — “It’s so haunting,” Amanda Gronich said as she and Moisés Kaufman looked at reproductions of decades-old, black-and-white photographs they’ve spent years pouring over.

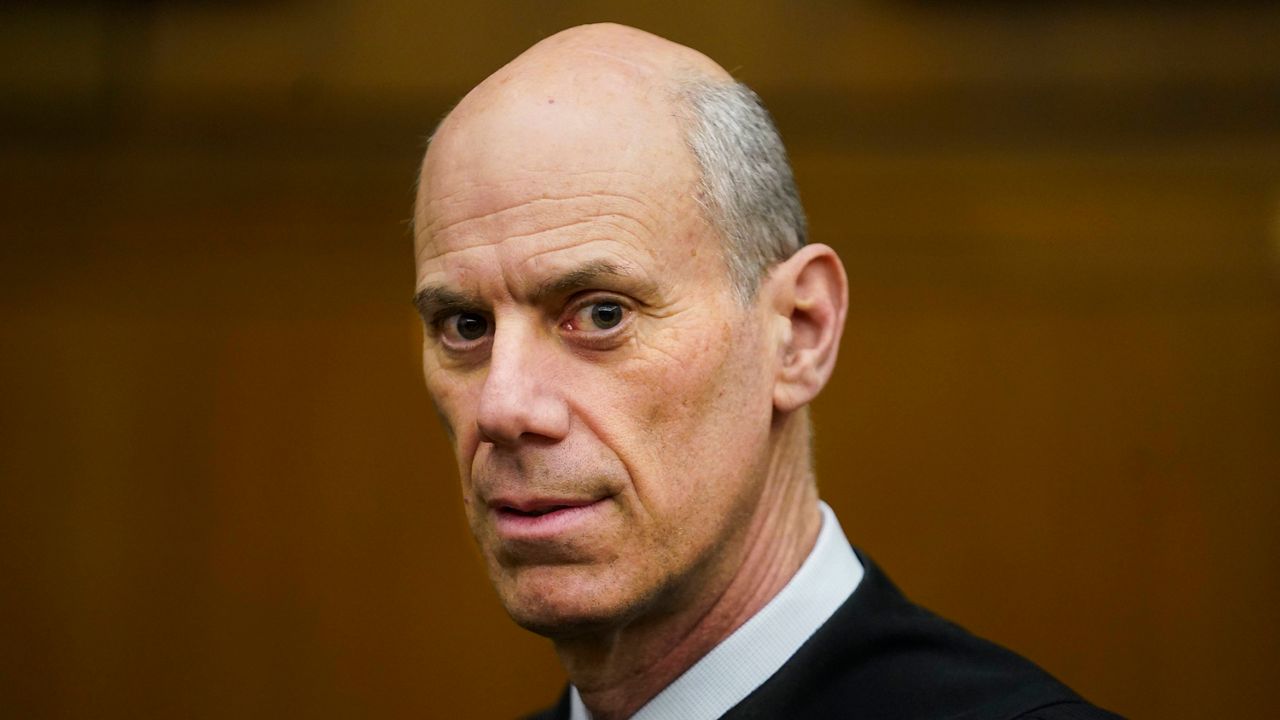

The duo have never shied away from haunting topics. They’ve worked together on a few productions over the past quarter century, including "The Laramie Project," a play about the murder of Matthew Shepard. Their latest project, “Here There Are Blueberries,” is currently on stage at the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts. It's also based on a true story, this one about a mysterious photo album that arrived at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in 2007.

“The album was photographs of Auschwitz,” Kaufman said. "But they were not photographs of the victims. There were photographs of the perpetrators."

Known as the Hoecker Album, it contains 116 photos that provided a never before seen look into the notorious concentration camp in Poland, where 1.1 million people — most of them Jews — were executed. But none of that is documented in its pages. Instead, these are essentially everyday snapshots of people relaxing, eating blueberries and decorating a Christmas tree — despite what we know what was happening just out of frame.

“I think that there is a common belief that the Nazis were monsters. And that is a convenient belief, right? Because if they were monsters, then they're not like the rest of us,” Kaufman said. “But I think that what you see in these photographs is that these are people who did monstrous things, but it also shows that we all have the ability and the capability to commit such acts.”

The playwright first read about the photo album in The New York Times and immediately felt a connection. His father is a Holocaust survivor. He had relatives at that same camp during the same months the photos were taken.

“So for me, it was like looking at the other side of a coin,” he said. "I'd always heard my uncle’s story. I'd always heard stories about other members of my family who perished in the camps. But this was an opportunity... to look behind the scenes... It gives you a glimpse into kind of what their mindset was."

Gronich is also the descendent of Holocaust survivors and says the album fills in some historical blanks. It contains the first and only known photos that show Josef Mengele at Auschwitz. And then, there’s a photo of a Rudolf Hess, the man who designed the concentration camp and served as Adolf Hitler’s deputy. In the picture, he is smiling, his pose casual, as he and a crowd of Nazi soldiers listen to a man play the accordion.

“It's one of the most chilling realities of the camp because now you see him frolicking on his day off,” Gronich said.

The play, which is based on years of research and interviews, tells two stories: the story of the discovery of the album and the search to understand it, and the story of a man in Germany who recognized his own grandfather in the images and went on a discovery mission of his own. But at the heart of the piece, the playwrights say, are the photos themselves and the story they tell about humanity, past and present. Gronich describes the experience of seeing the play as “stepping into the selfies of an SS officer.”

“In the 21st century, there's something really important about looking at the people who actually perpetrated the Holocaust in order for us to understand how human beings are capable of this, and to wrestle with how all of this reflects on the life that we’re living right now,” she said.

It's a cautionary tale captured in the camera lens of history.