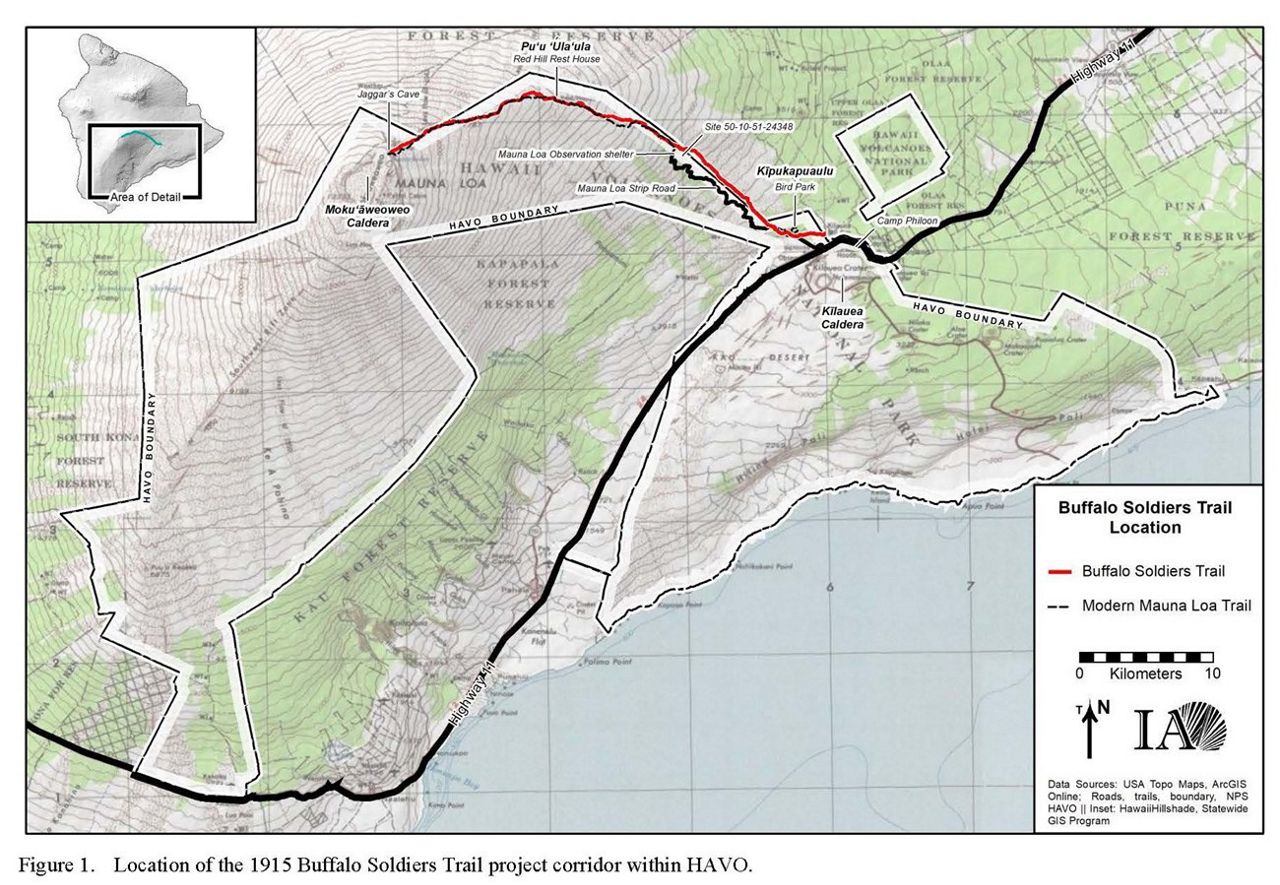

In 1915, the Buffalo Soldiers traveled by steamship to Hawaii Island, where they built a trail through rugged lava fields that connected the summits of Mauna Loa with Kilauea. The all-Black troops created much of the 30-mile trail by smashing lava with 12-pound hammers and filling up burlap sacks with small cinders.

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park librarian Martha Hoverson uncovered the details of how the Buffalo Soldiers, a U.S. Army regiment composed of African American men, built the Mauna Loa Trail after a park ranger asked her about it.

Thomas Jaggar, the founder of the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, which was established in 1912, wanted the Mauna Loa Trail built so geologists could have an easier way to access eruptions at Mauna Loa’s summit than the traditional ʻĀinapō Trail on the southeast flank of Mauna Loa.

“Thomas Jaggar was one of the ones really pushing to have this trail built,” said Hoverson. “He included some reports of the Buffalo Soldiers and their work in his weekly bulletins he produced for the Observatory. But mostly, what I was able to find was in local newspapers.”

Honolulu Businessman Lorrin Thurston, who was the owner of the Pacific Commercial Advertiser, one of the main newspapers in Honolulu, advocated for the creation of the Mauna Loa Trail. He thought the trail would expand tourism and, in turn, build support to create the park, which was established a year after the Mauna Loa Trail was completed.

“He wrote a lot of pieces himself about the trail,” said Hoverson, referring to newspaper articles she found in the Pacific Commercial Advertiser.

The Buffalo Soldiers first arrived in Oahu in 1913 and were stationed at Schofield Barracks until 1918. In 1866, congress created four military regiments made up of Black troops, all known as Buffalo Soldiers, including the 25th Infantry that came to Hawaii. It is believed that Native Americans gave them their moniker, because they were strong like buffalos or because the soldiers’ hair was similar to buffalo fur or perhaps because they wore hides in the winter.

Black troops were segregated from white troops — even in Hawaii. Black soldiers were also not allowed to climb the ranks of the military to become officers. It wasn’t until 1948 that the military was desegregated.

The Buffalo Soldiers with Company E volunteered to travel from Oahu to Hawaii Island to build the Mauna Loa Trail (formerly known as the Buffalo Soldiers Trail). About 150 men spent six weeks building the trail. During this time, half of the men would work on the trail for a week, while the others were free to do as they pleased. Then they would switch.

The work varied as the men confronted different types of lava on the path that would become the Mauna Loa Trail. When there was 'a'ā, which is a rough and jagged lava, the soldiers would smash it with a 12-pound hammer in an attempt to make it smooth and create a flat surface. If the trail was still too jagged, they would fill up burlap sacks with small cinders from the surrounding area and use them to cover the trail’s surface.

When the Buffalo Soldiers encountered “shelly” pāhoehoe, which is a type of lava that has a glass-like surface that can easily be stepped through and tear up one’s feet, they would use their large hammers to smash through it, revealing the smooth, hard surface beneath.

The manual labor was not challenging for the fit men, but what made the work difficult was that it was being done at heights up to 9,900 feet, where some people get altitude sickness. And during the time the trail was built, there were massive rainstorms.

“They were probably cold and wet and at high altitude, so they didn't have an easy time,” said Hoverson.

Hoverson said it was hard to find information about what the soldiers did on Hawaii Island during their free time, but she did find a newspaper article about the Buffalo Soldiers winning a baseball game in Hilo against a local team.

A year after the Mauna Loa Trail was built, other companies with the Buffalo Soldiers traveled to Hawaii Island and stayed at the recently built Kilauea Military Camp.

While visiting, Jaggar asked the Buffalo Soldiers to help him with his experiments. So, some of the men went down into Kilauea Volcano’s Halemaumau Crater and stuck a long metal pole into its lava lake. After the pole hit the bottom of the lava lake, they pulled it out. Based on where the lava adhered to the pole and the angle that the pole had been at when it went into the lava lake, Jaggar determined the depth of the lava lake.

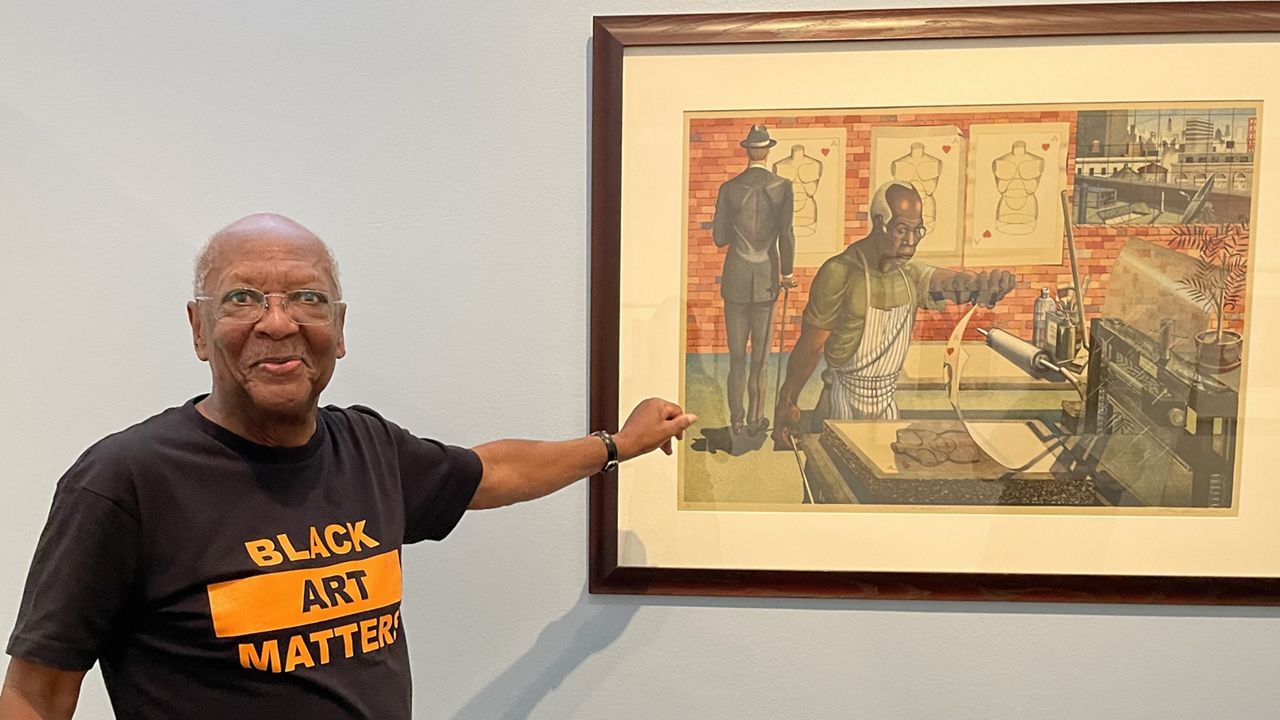

“Buffalo Soldiers were looked on by the African American community in the country as real success stories,” said Hoverson. She said there were a number of African American newspapers on the U.S. mainland that reported on the activities of the Buffalo Soldiers. “Their accomplishments were very well publicized.”

More than 100 years after it was built, parts of the Mauna Loa Trail can still be traversed. The trail was realigned when HVNP built the Mauna Loa Road, but anyone who wants to walk in the footsteps of the Buffalo Soldiers can hike from the Mauna Loa Lookout to the Red Hill Cabin. After the Red Hill Cabin, the Buffalo Soldiers marked the Mauna Loa Trail, but did not build this section. However, much of this latter section of the Mauna Loa Trail was covered by lava during the 2022 eruption.

Michelle Broder Van Dyke covers the Hawaiian Islands for Spectrum News Hawaii. Email her at michelle.brodervandyke@charter.com.