HONOLULU — The Honolulu Museum of Art recently acquired 55 prints by Black artists made between 1976 and 2014.

The prints, from Robert and Jean Steele’s collection, more than doubled the amount of art by Black artists in the museum’s collection.

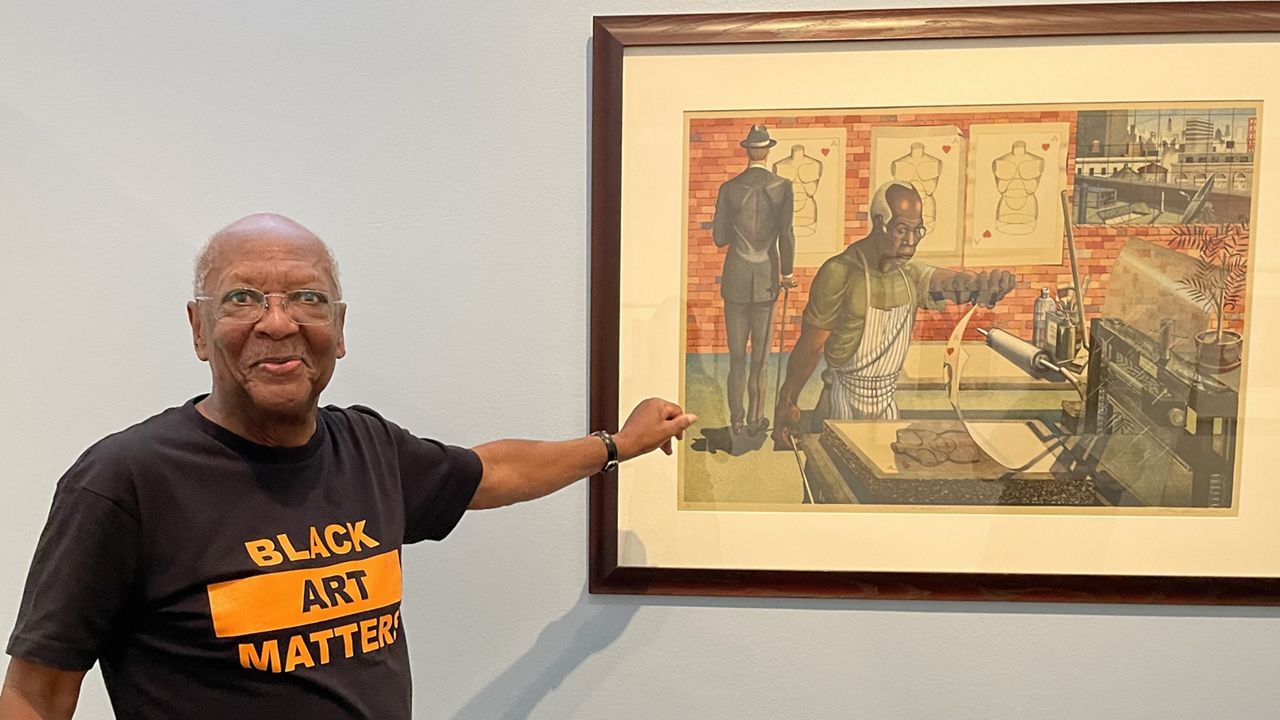

“One cannot truly understand the nature of American art unless one takes into consideration the contributions African American artists have made to the canon,” said Robert Steele.

Steele first became interested in art when he was an undergraduate student in the early 1960s at Morehouse College, a historically Black men’s college in Atlanta, and would visit the school’s art gallery. The gallery featured many of the artists he would eventually collect, like David Driskell, Romero Bearden and Jacob Lawerence.

In the 1950s, established Black artists started working in printmaking workshops and making limited-edition prints. Steele said the price point of the prints, which were much lower than six-figure, singular artworks, allowed him to collect art.

“There are two major traditions of printmaking, within the context of the African American community,” Steele said.

One stems from Robert Blackburn, who was the son of Jamaican immigrants and grew up in Harlem. He established the Printmaking Workshop in 1947 in New York. The other stems from James Lesene Wells, who was born in Atlanta. In 1929, he was hired by Howard University, a historically Black university in Washington, D.C., where he taught printmaking for 40 years. Both artists mentored other Black artists, who Steele would eventually collect works from.

“Between these two, Wells and Blackburn, a lot of African American artists were introduced to printmaking,” Steele said..

Katherine Love, an assistant curator of contemporary art at HoMA, said many of the prints collected by Steele were made in Black owned and operated printmaking workshops.

“The print studio is like a small community … It takes a lot of different people working together to create a work, a master printer, an artist, and technicians. So that community building and sharing was really important,” said Love.

A master printer “reinterprets the artist’s vision into print,” said Love. The prints can be technically complex, with different plates and many layers of ink.

“A lot of the mainstream printmaking operations were not accepting (of African American artists),” Steele said.

Steele met many of the printmakers personally after he started collecting their works 50 years ago. He recalls going to Blackburn’s printmaking studio, who directed him to meet Allan Edmunds, who founded the Brandywine Workshop in Philadelphia, and Curlee Raven Holton, who worked with the Experimental Printmaking Institute in Easton, Pennsylvania, and had been Blackburn’s student. He was also on the boards for many of the printmaking workshops.

“My whole idea initially was to … support the artist,” said Steele. “I realized that for these artists to be able to produce this work, they need the support of these workshops.”

“The next step in terms of supporting the artist is to make sure that quality work is placed in major museums,” said Steele.

The Steeles have also placed prints from their collection with the Yale University Art Gallery in Connecticut, the David C. Driskell Center in Maryland, the Mobile County Museum of Art in Alabama, the College of William & Mary in Virginia, and Morehouse College.

Steele decided to partially gift 55 prints from his collection to HoMA after seeing “30 Americans” in 2020, which was a traveling exhibition of works by contemporary African American artists from the Rubell Museum in Miami, Florida. HoMA completed the acquisition with funds from the John V. Levas Trust.

Seeing the “30 Americans” exhibit assured Steele that the museum would understand the significance of his prints. It also made him realize his prints would drastically expand the museum’s collection of art by Black artists.

“It’s really an important acquisition for us and it increases our representation of work by modern contemporary African American artists by quite a lot,” said Love.

Love said prior to this acquisition the museum had one piece by Faith Ringgold, an artist who grew up during the Harlem Renaissance in the 1930s and made work that varied from painting to quilting. Now, with the acquisition from the Steeles, the museum has 14 of her artworks.

Most of the prints in HoMA’s exhibit had been in Steele’s storage since he purchased them. He said it was wonderful to see them on display at the museum, which is “just a couple of miles away from my home.”

Steele moved to Hawaii seven years ago, after retiring from the University of Maryland. He and his wife wanted to be close to their daughter, Elisabeth Steele Hutchison, who moved to Hawaii about 20 years ago to work at the University of Hawaii at Manoa law school.

“It's a really great survey. You get a sense of what's happening in the printmaking community, especially with the African American printmaking community, (and) how artists have influenced each other,” said Love.

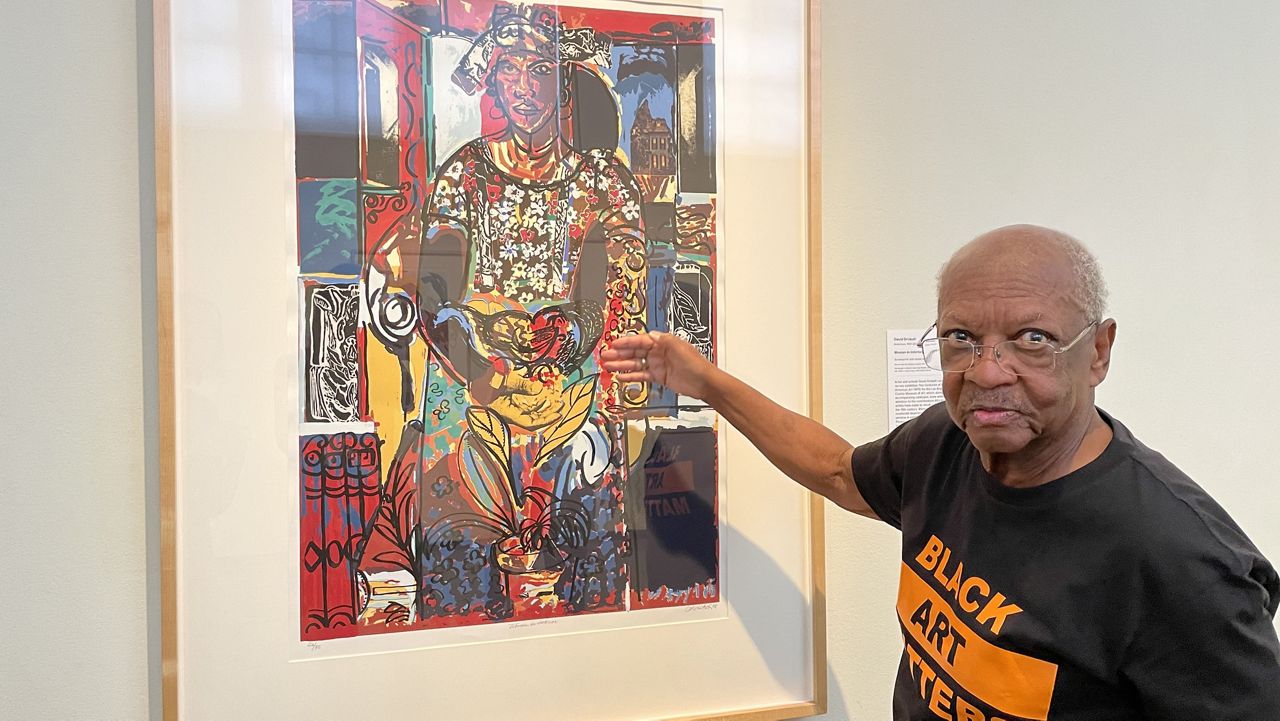

Many of the artworks use contemporary art forms, such as collage, Cubism or abstract art, and connect them with a Black identity by situating a Black figure in the works or incorporating Black culture, like jazz music.

David Driskell’s “Woman in Interior” (2008) includes a Black woman seated near paintings by artists Pablo Picaso and Henri Matisse, but her headscarf and the floral patterns that surround her connect her to her African heritage. In this way, the artist juxtaposes mainstream art with Black identity.

Akiemi Glenn, who is the founder of the Popolo Project, a nonprofit focused on bringing Hawaii’s Black community together, was a cultural consultant on “Forward Together.” She reiterated Steele’s sentiment that Black artists must be included when discussing the art canon.

“The presence of these artworks … really puts Honolulu Museum of Art … on the map as a place that is part of the global conversation on art. I don't think you can have a world-class museum without representing the work of people of African descent and especially African Americans, who have contributed so much, especially to contemporary art,” said Glenn.

The “Forward Together” exhibition will display 50 works, with 25 prints on view from Jan. 18 to May 12 and another 25 on view May 16 to Sept. 14.

The museum will also be hosting a conversation between artists Enrique Chagoya and Robin Holder, who will discuss printmaking. The event will take place March 22 at 7 p.m. at the Doris Duke Theatre.

Michelle Broder Van Dyke covers the Hawaiian Islands for Spectrum News Hawaii. Email her at michelle.brodervandyke@charter.com.