In 1973, it was widely assumed that while a daily jog might do a body good, running long distances was a hazard to your health. Just ask that poor messenger Pheidippides, who, legend had it, dropped dead after running from Marathon to Athens to announce the victory of Athenian forces over Persian invaders in 460 B.C.

It was also accepted as fact that suffering a heart attack was a flashing neon sign that your days of physical exertion were effectively over. You’d be lucky to return to your job, much less your fields of play.

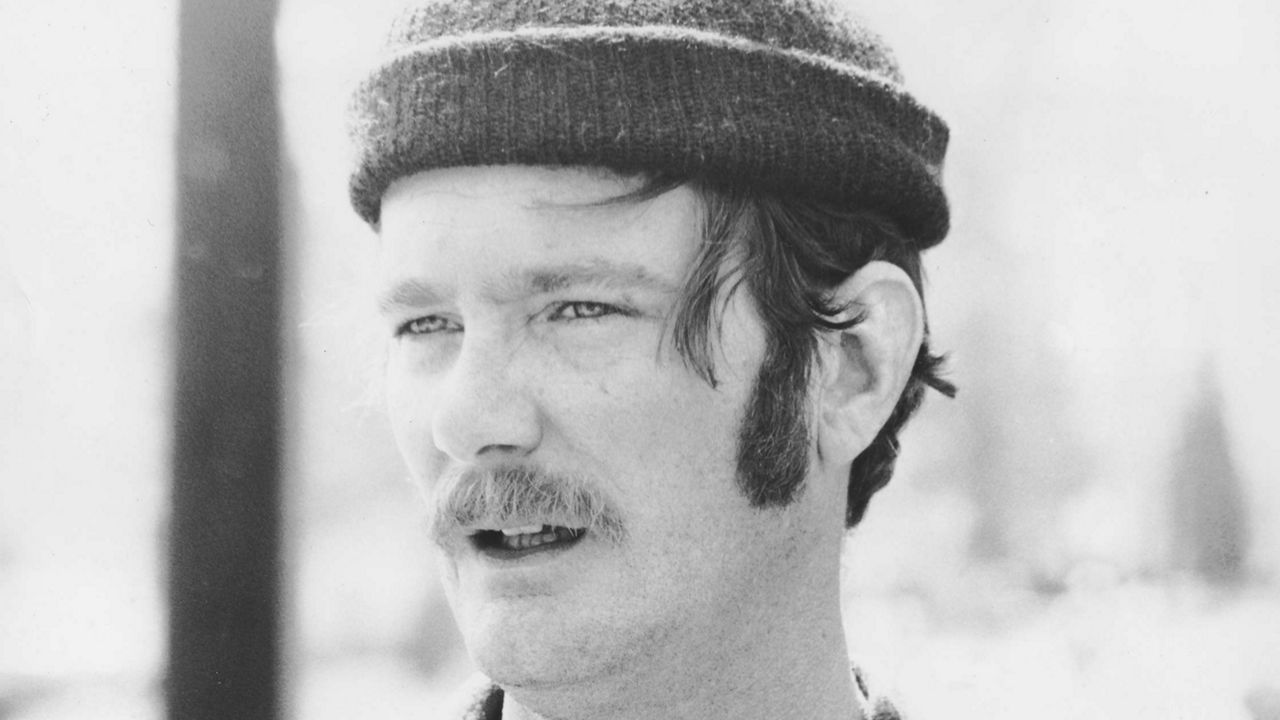

Honolulu cardiologist Jack Scaff begged to differ, and by the time the year was out, he would turn those assumptions on their head in dramatic fashion. In doing so, he changed the world of sports and medicine forever.

Scaff died at his home on Monday following a long illness. He was 87.

The son of a renowned metallurgist, Scaff was born in New York and attended the College of Wooster (Ohio) and Seton Hall College of Medicine and Dentistry (now the New Jersey Medical School).

While in medical school, Scaff spent time in the Philippines under a fellowship program offered by Smith Kline. On the way to his assignment in 1960, Scaff stopped in Honolulu, took in the view from the old Honolulu International Airport and recognized what he would later call “Heaven on Earth.”

After graduation, Scaff joined the Peace Corps and visited the islands twice a year to conduct trainings. In 1969, Scaff took a job with the Honolulu Medical Group and moved to Hawaii for good.

Here, Scaff and fellow cardiologist John Wagner, inspired by the groundbreaking work of exercise pioneer Kenneth Cooper and intrigued by new research conducted by pathologist Thomas Bassler—who claimed that a person who didn’t smoke and could finish a marathon in under four hours would not suffer a heart attack over the next six years—founded the Cardiac Rehabilitation Program at the Central YMCA.

The program operated on the premise that running could help people who had suffered a heart attack recover their health. Scaff, who years earlier had taken up running to alleviate a back condition, wanted to prove his idea by having his patients complete a marathon.

In 1973, Scaff entered the Boston Marathon to experience the race himself. While in Boston, he attended the American Medical Joggers Association Conference and met Bassler face to face.

After hearing about Scaff’s plans to have his patients train for a marathon, Bassler encouraged Scaff to organize his own “Honolulu Marathon.”

Back in Hawaii, Scaff approached the Mid-Pacific Road Runners Club, which sponsored the annual Oahu Marathon (now the Maui Marathon), to help organize the event. The group enlisted then-Mayor Frank Fasi, who pledged the support of the Honolulu Department of Parks and Recreation.

The first Honolulu Marathon, then called the Rim of the Pacific Race, was held in December 1973 and was a rousing success. Among the field of 162 runners were two of Scaff’s patients, Tahitian Lanai piano player Val Nolasco, who had suffered a heart attack two years earlier, and Ray Thiele, a pilot who lost his license after also suffering a heart attack. As part of a deal Scaff made with the Federal Aviation Administration, Thiele was reinstated after participating in the race.

Scaff’s early work as the Honolulu Marathon Association’s first president set the stage for five decades of growth and helped change how marathons were staged nationally and internationally.

From the start, Scaff wanted the race to be inclusive, to inspire as many people as possible to improve their health through proper training. To that end, he eschewed a set cutoff time for finishers, which has helped the race attract hundreds of thousands of recreational runners whose goal is simply to complete the distance.

Scaff also bucked against the rule of the Amateur Athletic Union, which required all participants in its sanctioned races to pay a $2 membership fee. As Scaff noted, AAU sanction was necessary for elite runners hoping to qualify for the Boston Marathon but was virtually useless for everyone else. And so, in typical poke-the-bear fashion, he dispensed with the fee for non-elite runners and resolved to tell the AAU, if it asked: “Well, my goodness, by coincidence we’re having two races on the same day, same time, same place” — one sanctioned, one not. No one ever asked, and within a few years, the AAU’s control over road races crumbled.

Scaff also circumvented AAU’s requirement that top athletes turn over any money they might receive to appear in a road race by arranging for top runners like Shorter to speak at the AMJA convention in Hawaii (held the same week) for an honorarium that just happened to match their travel expenses.

Scaff also initiated the marathon association’s first dealings with future title sponsor JAL via its advertising agency Asatsu (now ADK). Working with Asatsu executive Jiro Kitamura, Scaff established a sister race in Japan, the Miura International Citizens Marathon, in 1981. Each year, three participants are chosen via lottery to participate in the Honolulu Marathon. Early promotions in Japan helped to raise the marathon’s profile in Japan. In the years to follow, Japanese runners would account for as much as two-thirds of the Honolulu Marathon field.

The charismatic, quip-slinging Scaff rose to national prominence with his audacious leadership of the marathon association, epic running adventures and involvement with other ambitious running events. Writer and former Olympian Kenny Moore famously captured his outsized personality in a 5,600-word article in Sports Illustrated when he described him as “at his Napoleonic best when laying down the law of philosophy.”

Scaff went on to help found the Great Aloha Run and organize the 1997 Trans-Koolau Trek over the newly constructed H-3 freeway but left the marathon association in 1981. He still remained synonymous with the race for decades to come.

Despite this, Scaff said his greatest legacy is not the Honolulu Marathon but the running clinic he founded to help everyday people train for the event.

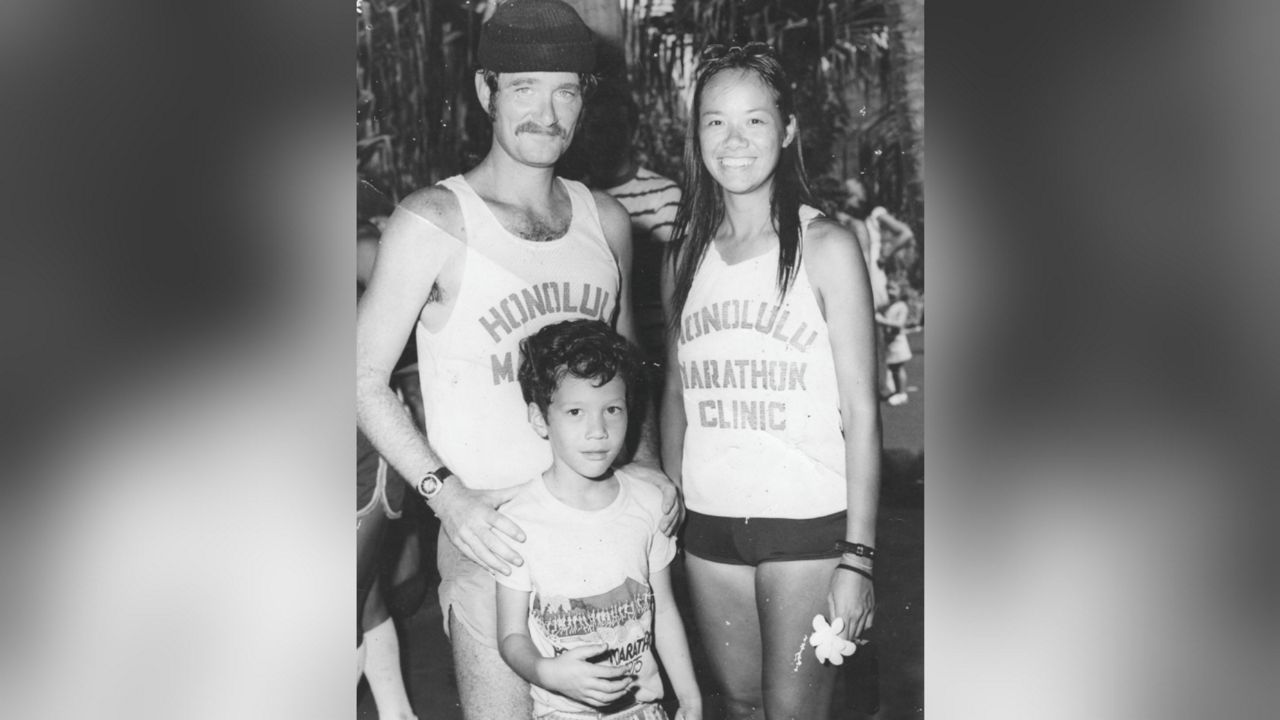

Scaff worked with Parks and Recreation physical fitness specialist and former Olympic champion Tommy Kono to establish what was initially a network of clinics around the island in 1974. Over the years, the clinics consolidated into what yet survives as a single meeting every Sunday at Kapiolani Park.

Run by volunteers, many who trained for their first marathon with the clinic, the free Sunday gatherings feature a short talk on marathon preparation followed by group training runs organized by experience level. Until just a few years ago, Scaff gave the early morning talks himself. Following a massive stroke two years ago, he returned briefly via video to continue his practical lessons on the LSD (long, slow distance) training he developed to help thousands of novice runners go farther than they’d ever dreamed.

For local runners sometimes lost in the shuffle of a race that, prior to the pandemic, had become highly calibrated to the needs and desires of foreign runners, the clinic is at the heart of the marathon experience, the thing that makes a highly personal challenge also inter-personal.

“It’s spectacular to be a part of the clinic, to be part of that fellowship,” said Honolulu Marathon Clinic Board president Bruce Mulliken, who trained with the clinic for his first marathon in 2001. “Jack loved everybody. He loved the running. He loved helping everyone he could. He was just a remarkable person.”

For local runners, one highlight of the year used to be the carbo-load party Scaff and his wife Donna hosted every marathon week at their Roundtop home. Though sometimes described as Gatsby-esque, the parties were any but. There millionaire bankers and Waikiki dishwashers pulled from the same tap and listened to Scaff toggle from what ails the modern marathon to the latest medical research (Scaff himself authored numerous scholarly articles over his career) to tales from his and Donna’s annual trip to Carnival. Those who stayed late enough would eventually hear a sentimental Scaff cycle through the same loving reflections on Donna and his sons Jack III and Kawika.

The couple’s annual chili cookoffs were much the same.

“He opened his home to everybody,” Mulliken said. “There was always a barrel of beer right by the door and you just helped yourself. All were welcome.”“He opened his home to everybody,” Mulliken said. “There was always a barrel of beer right by the door and you just helped yourself. All were welcome.”

An iconoclast by nature and reflex, Scaff lived long enough to be embraced by the establishments he once challenged. Among numerous honors, he was the first Hawaii resident to be named a fellow of the America College of sports Medicine, the first inductee to the Honolulu Marathon Hall of Fame and a member of the Hawaii Sports Hall of Fame.

The honors were meaningful to a born lightning rod who received as many barbs as accolades over the years. Yet friends said he remained unambiguous about what mattered most to him.

In 2011, Honpa Hongwanji Mission recognized Scaff as one of its Living Treasures of Hawaii. At the ceremony, he was asked what he would be if he was reincarnated.

“Well,” he responded, “if she’d let me, I’d like to come back as Mrs. Scaff’s next husband.”

Scaff is survived by his wife Donna; sons Jack III (Julie) and Kawika; granddaughters Margaret and Emma; brother Walter; and sister Anne. Services are pending.

Michael Tsai covers local and state politics for Spectrum News Hawaii.