Though Hawaiian false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) have been kama`aina for thousands of years, they are one of the most endangered marine mammal species along the island chain, according to scientists.

Currently, there are only 167 false killer whales believed to be left, said Cascadia Research Collective research biologist Robin Baird in an interview with Spectrum News Hawaii. Baird received his Ph.D. in false killer whale behavior and has been studying marine mammals since 1985.

Scientists don't quite know exactly how long they have been kama`aina, but false killer whales diverged from their closest relatives about 3.3 million years ago, Baird said, and would have been present in the central tropical Pacific for the last couple million years.

“There is evidence that back in the 80s the population was probably about twice to three times as large as it is now,” said Baird. “And that decline from the 80s to the 2000s in the 2010s is one of the main reasons the population was listed as endangered.”

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association Fisheries, the false killer whale’s historical population size is unknown, but spotter planes from the 1980s report seeing large aggregations of 350-400 whales in a single area.

Referred to as koholā and revered as the embodiment of Kaunaloa (the god of the sea), false killer whales hold a significant presence in Hawaiian culture.

“[Kohola] are revered as messengers between the living and the dead,” explained Jordan Lerma, a research assistant and UAV operator for Cascadia Research, to Spectrum News Hawaii. Lerma said that honoring and worshipping deities in the ocean comes from ancient Hawaiian fishing practices and religion. One can still witness these rituals taking place today, when a foreign cultural practitioner will go out on the beach while fishers make a blessing.

From all accounts and research, the species, dark gray members of the dolphin family, are incredibly social, highly sentient and intelligent and live about 60 years. They have culture, like humans, and mourn their dead just as we do.

They are similar to humans, according to Baird. Females can probably first reproduce around 10 years of age, and the interval between calves is actually about seven years, which is the longest recorded for any species of dolphin, he continued.

Mothers nurse their young for three years and have one of the longest known maternal-child relationships in the world. Females probably continue to reproduce until their early 40s, and then go through menopause and live at least into their 60s but possibly into their 70s; longevity for males is thought to be in the 50s.

Lerma only realized in his mid-20s while drone-filming the waters and whales on the southwest coast of Kauai that false killer whales were native to the islands. As a youngster on the Big Island, his only marine mammal education had been with Dolphin Quest, which is the case for most keiki across all islands, or Sea Life Park for those on Oahu.

False killer whales are rarely spotted by locals on land, but often spotted by fishers, according to Lerma, who is Native Hawaiian and grew up in Hilo where his grandfather was a fisherman.

As Lerma grew more interested in dolphins and whales, he started working with Baird, who visits the islands for a few months a year for research missions with his Olympia, Washington-based team. They were last in Kona in November. A typical trip involves days of filming, following false killer whales around the islands while taking biopsy samples to study their DNA.

“If they're hunting fish, they'll bring the fish to the boat … put it right in front of the boat, put their head on the water and stare at you [as if they're saying] `Here! Here's some fish, have some fish!’” said Lerma.

“You don't see this often with other species. They'll pass fish back and forth between each other and share if there's like an alpha male or female in the group and sometimes the juveniles have a hard time catching fish and you will see an adult catching a big fish and just pass it to the juvenile. It's that culture where you know their ability to survive is one individual's evolutionary advantage. They evolved as a group to work together and that's kind of a beautiful thing.”

According to Baird, false killer whales are an open ocean species and have not been the subject of much research attention worldwide, and Hawaii is one of the few areas where they regularly come close to shore. From the work Baird and his team have done in Hawaii, the endangered Hawaiian population is among the most well-known of false killer whales anywhere in the world.

But the biggest question is why are these inspirational and intelligent animals disappearing so dramatically?

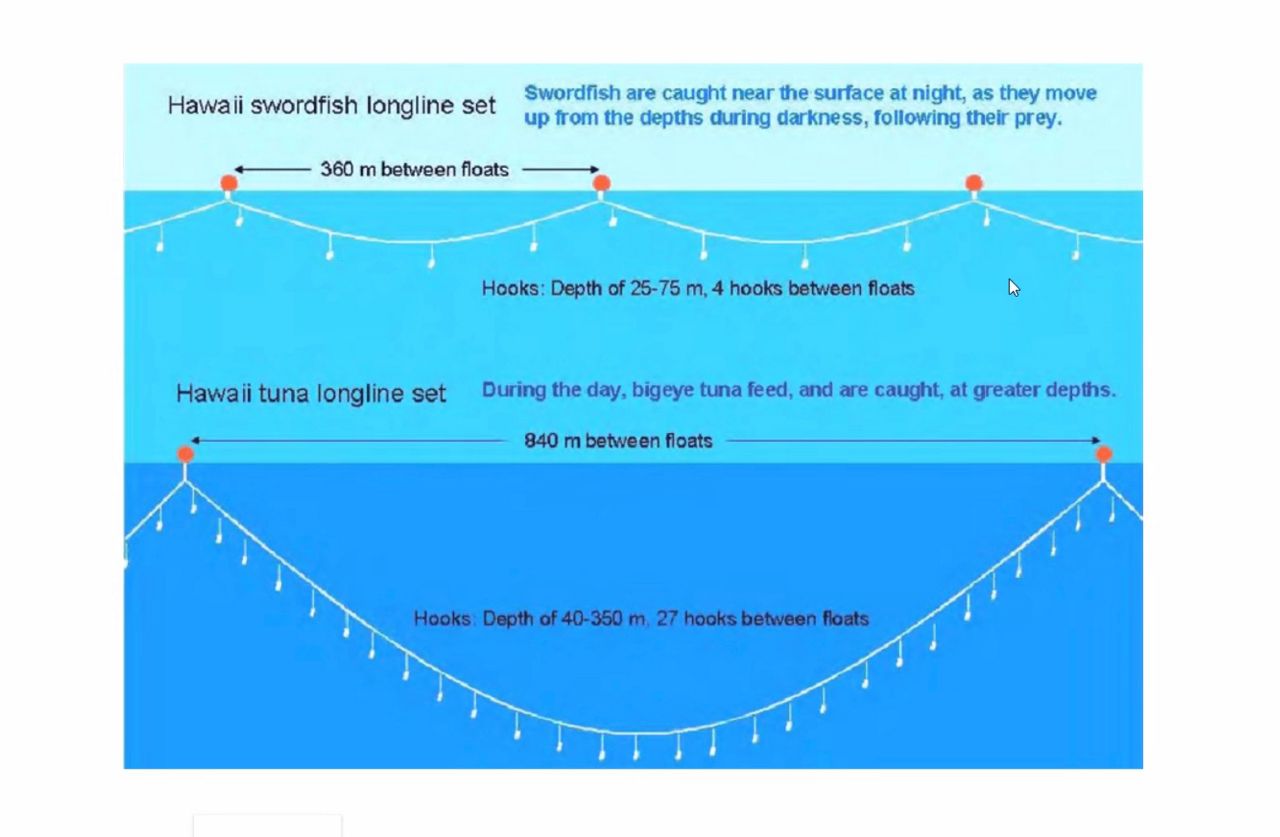

“The biggest problem for false killer whales is bycatch,” Baird emphasized.

“They feed on the same kinds of things that humans like to catch. They eat ahi, mahimahi, ono, monchong,” said Baird.

“But in the case of false killer whales, the bycatch is where they try to take the fish off the line and end up getting hooked. And so when they get hooked, sometimes they or they die outright. Sometimes they struggle against the gear and break off, having swallowed the hook or having been hooked in the mouse. And then sometimes they sometimes they get wrapped up in the gear and drown.”

What can we do to help?

“[We need to make sure] that the community is better off by sharing the information of where the animals are. There's fish aggregating devices around all the islands, right? If a fisherman knows [where the killer whales are], he can tell other fishermen not to go to there because they're not going to catch fish there. When there are animals around fish don't bite or there's no fish at all. If we syndicate that information out so that the animals aren't going after fishing line, [then] fishermen are actually catching fish. The solution needs to benefit both parties, otherwise, it's not going to work,” said Lerma.

“We found that talking to kids is a good segue to kids talking to their parents and their uncles, aunties about the importance of these animals and getting them involved in sending photos to the catalog so that we can better understand movements and habitat use. It's a couple things: addressing the current threats with finding a way to make fishermen and the animals better off,” said Lerma.

“One species that's actually benefited from the overfishing of ahi is mahimahi — mahimahi populations have actually exploded," said Baird. "If you're going to eat fish eat mahimahi. It's just a great fish to eat."

For more information on false killer whales in Hawaii and protecting them, visit Cascadia Research Collective, as well as the NOAA Fisheries site.

Nuy Cho is the executive producer of Spectrum News Hawaii. She writes the surf report and covers other general news. Read more of her stories here.