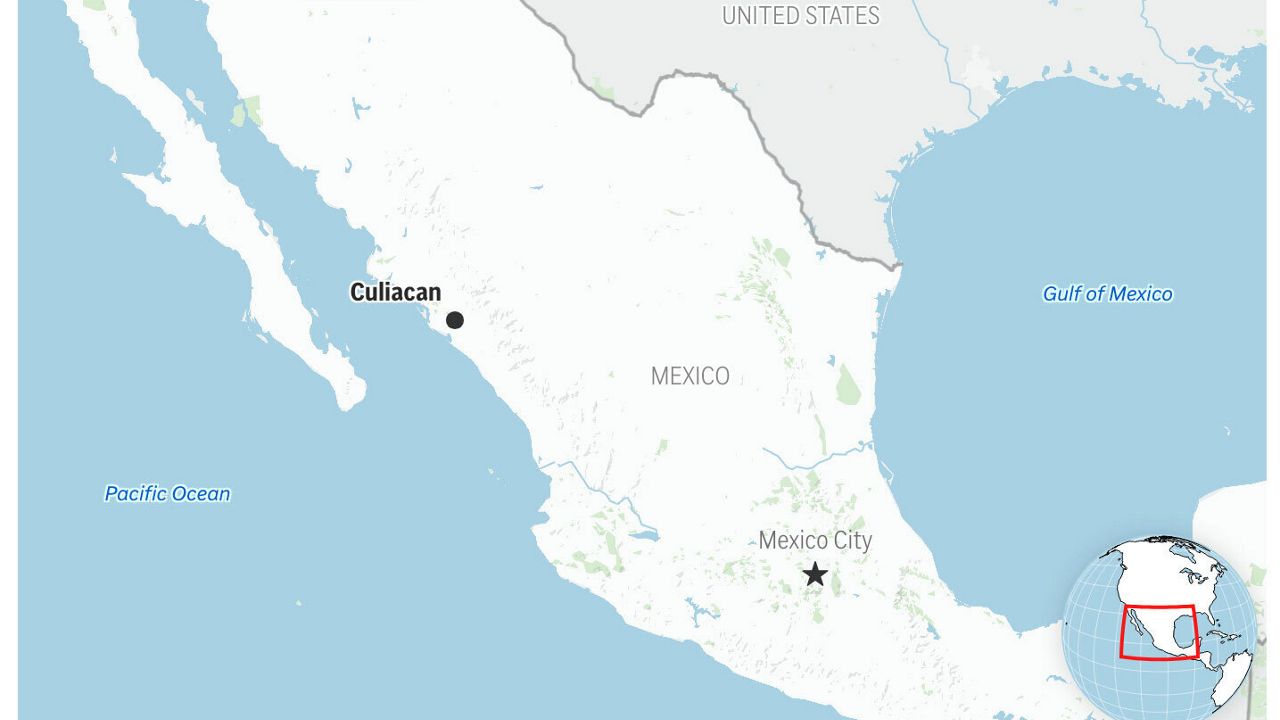

MEXICO CITY (AP) — Schools and businesses in Culiacan, the state capital of Sinaloa, remained closed and festivities around Mexican Independence were canceled Thursday as fears over clashes between factions of the Sinaloa cartel disrupt life in the northern city of 1 million.

Sinaloa Gov. Rubén Rocha and outgoing President Andrés Manuel López Obrador – both of the ruling Morena party – have downplayed the tensions, which started Monday, and said that local, state and federal forces are ensuring safety in the area.

But despite the recent deployment of special forces soldiers, planes and heavily armed helicopters, the fear continues. Even Rocha recognized that the clashes, which have followed the arrest in the U.S. of two cartel leaders in late July, could continue.

Security forces are “dissuading some violent acts but above all reducing the risks to the population to a minimum,” Rocha said in a video posted to social media Thursday.

Still, for safety reasons, he said “there will not be any celebration” for the Sept. 15-16 holiday, adding that school will be suspended Thursday and Friday because so few students showed up.

In 2008, a grenade attack in the city of Morelia, west of Mexico City, during the independence celebrations killed eight and wounded dozens, in what was an unusual cartel mass attack on civilians.

The Sinaloa governor maintained the state has sufficient security presence to protect people, but around Culiacan people appear to have a very different view.

“The government doesn’t control anything, absolutely nothing,” said Ismael Bojórquez, director of the weekly newspaper Riodoce in Culiacan, which specializes in coverage of organized crime. “There is a lot of fear. The people are defenseless.”

As an example, he said that on Tuesday, gunmen in a convoy of 15 trucks drove into the city and later left without any authority stopping them.

Bojórquez said that cartel gunmen have their shootouts, kidnap and burn, then the government arrives to clean up and take away the burned vehicles.

Faced with inaction from the government, residents took their own precautions including not sending their children to school, he said.

Juan Carlos Ayala, a professor of philosophy at the University of Sinaloa, said that just between Wednesday and Thursday he came upon three shootouts.

“The city appears empty,” he said. “They’re clashing everywhere.”

He noted that the internal clash created a lot of uncertainty. “They all know each other, they know where each other lives. They come, wreck the houses, take relatives.”

A 65-year-old retiree named Jesús, who lives in a rural community on the outskirts of Culiacan and gave only his first name for safety, said he had asked his children to leave his grandchildren home and to not believe that things are calm even if the government says so.

As of Wednesday, the state prosecutor’s office had reported nine dead, eight injured and 14 abducted, but the actual number of fatalities may be higher since the cartels often pick up their own dead.

The surge in violence had been expected after Joaquín Guzmán López, a son of former Sinaloa cartel leader Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, landed near El Paso, Texas, on July 25 in a small plane with Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada.

Zambada was the cartel’s elder figure and reclusive leader. After his arrest, he said in a letter circulated by his lawyer that he had been abducted by the younger Guzmán and taken to the U.S. against his will.

Now there appears to be a struggle for power between the remaining sons of El Chapo, known locally as “the Chapitos,” and those loyal to Zambada.

“There’s obviously a fight for power” inside the cartel, Bojóquez said. “The only thing the government is doing is watching, observing the clash between the Chapitos and El Mayo’s people,” he said. “There’s no action against the drug trafficking cells.”