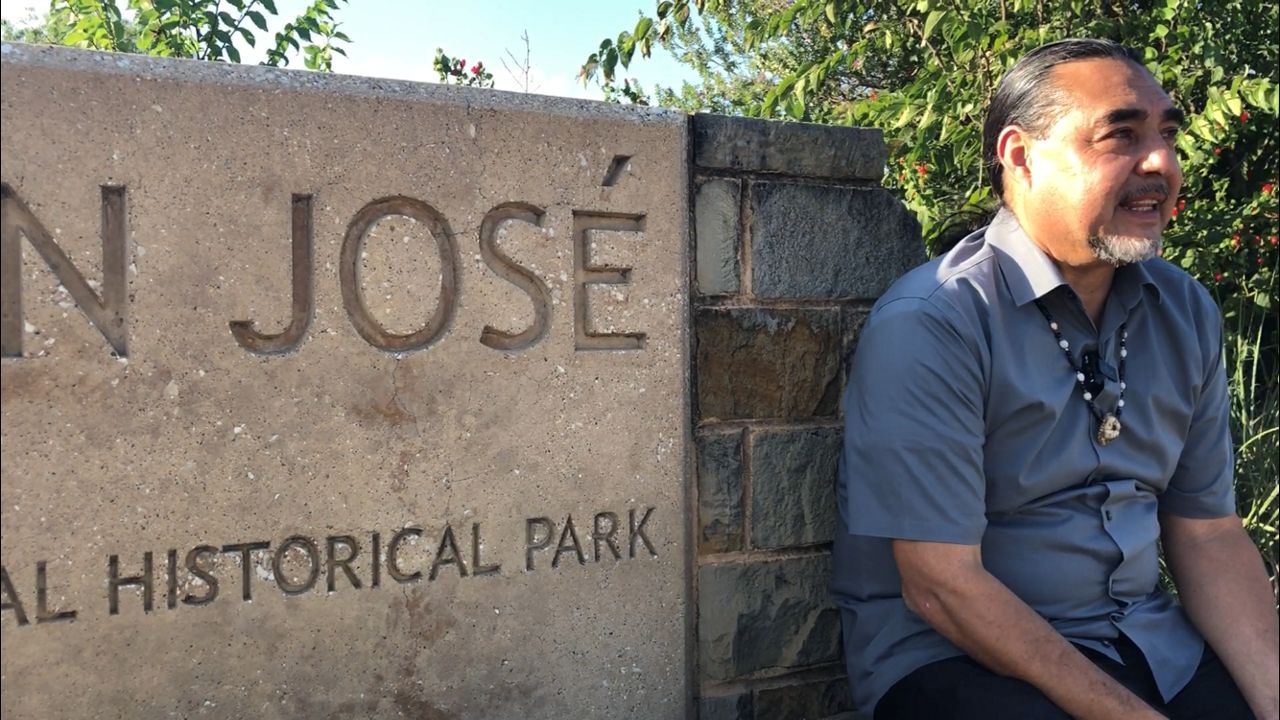

SAN ANTONIO — Ramon Vasquez took a stroll by 300-year-old Mission San José and it reminded him of the constant battles and he the Indigenous people face. He's a member of the Tap Pilam Coahuiltecan Nation.

“We’ve said for many years now, the American Indians that came out of these missions are always the afterthought, we are always the afterthought,” Vasquez says.

Vasquez sat in front of the mission as a Texas Park Ranger was driving around the lot of San José.

“They always get nervous when they see me out here,” Vasquez says.

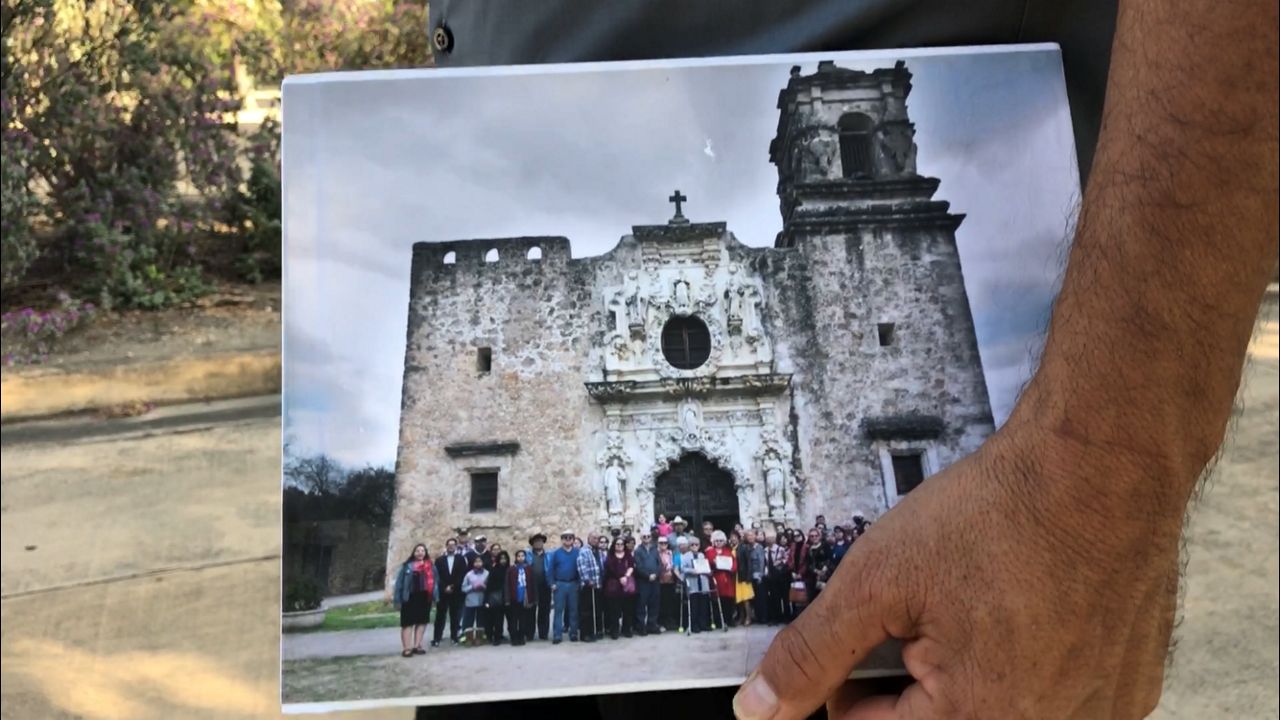

Nervous, he says, because he's very vocal when it comes to preserving Indigenous culture. He's made his voice heard with the help of the nonprofit American Indians of Texas at the Spanish Colonial Missions. Vasquez held up a book that featured two families who were descendants of the mission.

“There are thousands and thousands of decedents from San Antonio missions alone,” Vasquez says.

His latest concern — a new, 20-foot mural commemorating 300 years of Mission San José. The design has already been approved by a panel including National Parks, which runs the missions. However, Vasquez says some descendants weren't interviewed by the artist. Based on what he knows so far, he's worried the art won't accurately portray the Indigenous community that made up San José’s history.

“It’s dangerous because it’s promoting false narratives. That’s what makes it dangerous. Here we should be promoting accurate, authentic, historical representation of a community,” Vasquez says.

National parks did say descendants of the community will get a first look of the mural before its unveiling. A compilation video of them describing their love of the community — in three words — will also be a part of the virtual unveiling.

Vasquez says more should be done though.

“You know, an authentic criteria that can inform the artists how to depict this, this very public image that millions of people will see,” Vasquez says.

Something as simple as an art project, Ramon says, can hurt a generation.

“When you erase a history of a people from a physical location, that’s called cultural genocide,” Vasquez explained.

Whether it’s a mural or mascot Vasquez continues to speak up for Indigenous people.

“I’ve said it plenty of times, what kind of man starts a fight to let their children finish it,” Vasquez says. “We’ve had to do that for the past 30 years so we are going to finish this fight at some point.”