This is part two of our profile on Ramón Hernández in celebration of Hispanic Heritage Month. To read part one, click here.

SAN ANTONIO — After traveling three-quarters of the world, Ramón Hernández returned to San Antonio, where he wanted to venture into the music industry.

“After I retired from the U.S. Navy on May 31, 1983. About 6 months later, I approached the San Antonio Express-News, it really wasn’t a complaint but a suggestion that they should really write more about Tejano artists, or Latino artists or Hispanic artists, whatever term you want to use,”Hernández said.

Hernández felt he was more than qualified to write about the entertainment industry due to his experience as a disc jockey overseas and in Hollywood.

“The response I received was ‘Chicanos don’t read',” Hernández recalls.

He didn’t agree with that notion. Back then, Hernández said Chicanos would have to drive to San Antonio’s West and South Side and read posters nailed to telephone poles in order to learn about Tejano musical events that were happening in the city. Hernández made a deal with the paper.

“I said, 'you know what, if you allow me to do one article a week on a Tejano artists, a Chicano artists, Mexican artists, I guarantee you subscriptions will go up,'” Hernández says.

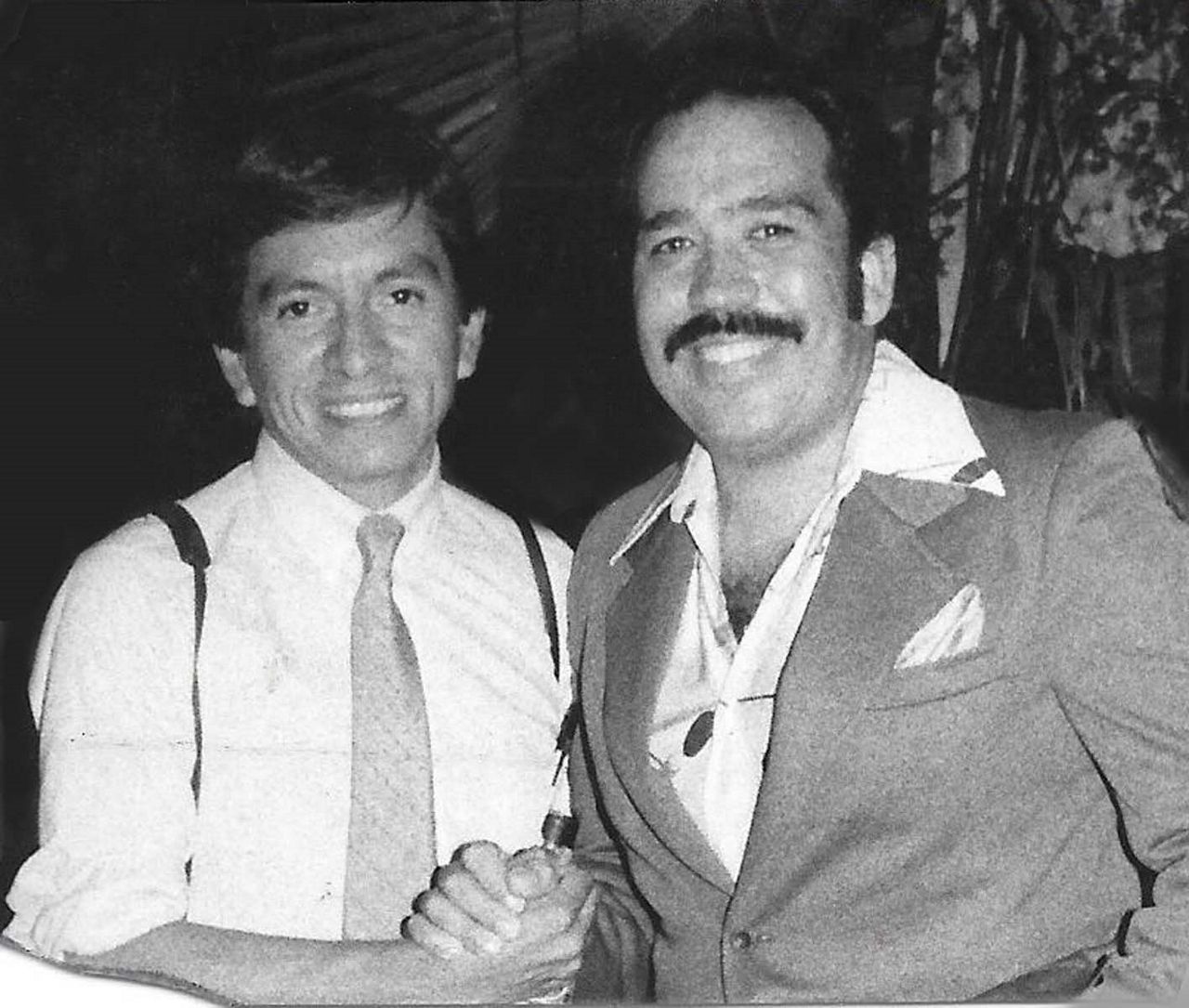

After Hernández wrote a piece on legendary Tejano artist Freddy Fender, he said more Latinos started to read the paper.

“It’s important. It is our culture, it’s not Mexican music, it’s not Anglo-Saxon music, it’s not Black music,” Hernández says. “It’s the music that Chicanos created.”

He made it a priority to cover Tejano stars such as Sonny Ozuna, Little Joe and the older pioneers who were dying off, like Juan Gaitan. He also wrote about young rising talents, like Selena Quintanilla, who Hernández saw perform at Rosedale Park on San Antonio’s West Side.

“I met her in 1985, at the end of 85 — I took her first publicity picture, I did the first interview ever with Selena (Quintanilla,)” Hernández says.

He developed a strong relationship with the Quintanilla Family and eventually became their photographer for four and a half years.

“Her humble beginnings, the period where you sacrifice, when you ride a bus without a heater, without an air conditioner,” Hernández says. “When you don’t have costumes yet, when you don’t have hairdressers, a sound man or a light man. They did it all themselves.”

Hernández never charged the family a dime, and eventually they parted ways when Selena signed with Capitol Records, but he always kept in touch with the Quintanilla Family.

Hernández still keeps Tejano culture alive in his writing with his magazine Street Talk Magazine, and his latest book on Little Joe, called The Latinaires, Little Joe y Mas.

He also donates the priceless memorabilia he gets from his interview subjects. The Wittliff Collections at Texas State University has received all of Hernández's Tejano music materials and memorabilia making it one of the largest known collections of Tejano Music, which spans from 1922-2019. The 12-series collection is named after Hernández and is available online.

Hernández was once offered $10,000 for an outfit of Fenders, but he declined the offer.

“I will not bastardize or take advantage and use any of this to make a profit,” Hernández says. “First of all, it belongs to the people. It’s for them that I do it, I don’t do it for myself.”

Hernández says he’s been writing, photographing, documenting these musicians and events for the last 40 years so he can leave something behind for his people.

“Just the gratitude and the heartfelt abrazo [spanish for hug.] That’s all you need, that’s all you want — that’s satisfying,” Hernández says.