NATIONWIDE – It should come to no surprise that football is the most popular sport among fans in the United States, and with the season quickly approaching during a pandemic, there are many lingering questions about how to conduct a high-contact sport that often gathers tens of thousands of people.

What You Need To Know

- Football season faced the flu pandemic in 1918

- NCAA Division I Council voted to lift moratorium on voluntary workouts effective June 1

- Coaches, players fell sick in 1918; schedules shortened or forfeited

- NFL focused on testing prior to training camps in July

On an encouraging note, this isn’t the first time football has faced this kind of dilemma.

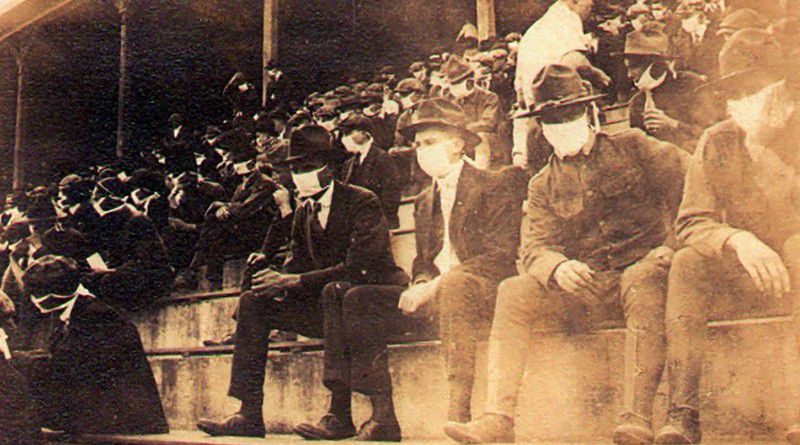

The 102-year-old image above shows a black-and-white photo from a Georgia Tech football game at Grant Field in 1918. Decades before tailgates, prime-time kickoffs and billions in program-supporting TV money, the ethos of the die-hard college football fan was not much different than today—there may be risks, but we’re going to the game.

READ MORE | AHL Cancels Remainder of Season, Ending Texas Hockey Rivalry

And once fans are allowed back in stadiums, history has shown that football could come back strong.

“That’s really what started the big boom of college football in the 1920s,” said Jeremy Swick, historian at the College Football Hall of Fame. “People were ready. They were back from war. They wanted to play football again. There weren’t as many restrictions about going out. You could enroll back in school pretty easily. You see a great level of talent come back into the atmosphere. There’s new money. It started to get to the roar of the Roaring ’20s and that’s when you see the stadiums arm race. Who can build the biggest and baddest stadium?”

A comeback seems a long away off, even as some schools try to prepare for what many hope will be a full season this fall. For now, discussions are still dominated about what can be done safely.

“I think there are parallels in what we can learn from 1918 in terms of how we respond to a pandemic,” Georgia Tech professor of sports history Johnny Smith said. “The cities that were hesitant and didn’t impose closure orders as quickly had far more fatalities. I think the lesson we can draw in general from 1918 about how to respond to a pandemic is that closure orders and social distancing is effective.”

The NCAA Division I Council voted Wednesday to lift a moratorium on voluntary workouts by football and basketball players effective June 1. This decision clears the way for individual workouts by athletes, mostly on their own, subject to safety and health protocols decided by their schools or local health officials.

READ MORE | How to Practice for a High School Football Season that Remains in Limbo

College football commissioners in mid-April insisted sports cannot be played this fall if campuses are not open, a stance echoed by NCAA President Mark Emmert. But, large universities including Notre Dame, LSU, and more have announced plans to reopen campuses for the fall semester and conferences have begun setting up plans for how to play football amid the pandemic. The latest came this week with the Florida State system announcing plans for its 12 schools and more than 420,000 students.

On the other hand, the California State University system--which claims to be the nation's biggest four-year university system--plans to cancel nearly all in-person classes through the fall semester to reduce spread of the coronavirus.

With that, many questions remain, including specific safety protocols and whether fans would be allowed if games proceed.

Ohio State athletic director Gene Smith said in conference call Wednesday that he believes the Buckeyes could safely play home games with 20,000 to 30,000 fans in its 105,000-seat stadium.

“I think we can get there,” Smith said.

READ MORE | Little League Season Up in the Air

Amid the lingering effects of World War I, there were restrictions on travel, practice and number of games played, similar to today’s circumstances. The storied Army-Navy game was canceled in 1918 and the lone postseason game was the 1919 Tournament East-West game in Pasadena, California, a game better known today as the Rose Bowl.

The pandemic sickened players and coaches, shortened seasons and even forced some universities to scrap their seasons. On October 13, 1918, The Washington Post carried a story that declared the epidemic “sweeping the country has dealt the death blow to necessary preparations, and with the stage still undetermined, the outlook is anything but bright.”

Penn coach Bob Folwell, better known as the first coach of the New York Giants, was hospitalized with Spanish flu and missed six weeks during the 1918 season. West Virginia failed to field a team and at least one player died when he ignored a cold that morphed into the virus. The Missouri Valley Conference, which included Kansas, Kansas State and Missouri, shut down for the season. Pittsburgh and Michigan shared the national championship, though neither team played more than five games and all but one was held in November.

In September 1918, the second and by far deadliest wave hit in the U.S., the final blow for teams trying to schedule a full season. The headlines that followed included “Masks for Michigan Men” (Daily Pennsylvanian, October 23) and “Rough Year For Football, But Game Shows Its Mettle” (Chicago Daily Tribune, October 21).

“A lot of them closed up camp, especially once the second wave hit,” Swick said.

The pandemic killed more than 50 million people worldwide, including 675,000 in the United States. Even with lower numbers in 2020, Smith said, fans will still be cautious.

“I think generally people are going to be more hesitant to return to stadiums today,” Smith said. “I think there will be a certain segment of the population that is more concerned about a second wave. That’s another lesson to keep in mind from 1918.”

READ MORE | Kamaka Hepa Returns to Alaska After UT Campus Shut Down

Much more is at stake from a century ago: TV money, bowl games, conference championships, cross-country travel all need to be sorted out. In 1918, there were no more than 90 college football teams. There are 130 major college football teams alone in 2020, spread across 41 states and competing in 10 conferences.

On the professional level, the NFL faces the same limitations including government restrictions, testing and social distancing.

Dr. Allen Sills, the NFL’s chief medical officer, noted during a conference call following the team owners’ virtual meeting Tuesday: “We’re not putting dates on the calendar at this point” concerning getting coaches and players into team complexes.

“We feel there are certain important steps that need to occur with regard to testing, with regard to test availability, with regard to test reliability, and our continued evolution of understanding about how to manage exposure,” he added. “All of those things continue to evolve, and when we and the players association together feel like we’re at a point of satisfaction with that science, then we’ll be ready to move forward. We’re moving as fast as the science and the data takes us.”

Cass was willing to put a time frame on it — somewhat.

“We believe by the time of training camp (late July), we’ll be able to test players and coaches multiple times a week, and be able to get the results fairly quickly,” he said. “I think there’s a really good shot that we’ll be OK.”

READ MORE | Texas’ Sterns Motivated for Football to Return

To play or not to play is still the essential dilemma a century later but football — and sports — will return at some point, as it did in 1919. The Ogden Standard noted after the sport’s yearlong break in the state it was “anxiously awaiting the rustle of the cleated shoes, the line plunges of victory and the return of the greatest of all college sports.”

“People really wanted to get back to their lives,” Smith said. “Sports is all about the human experience, human connection. We’re not meant to be isolated. That’s a frustration a lot of people have in 1918 and today. I think people not being able to attend sporting events is symbolic of a larger sense of loss in America.”

The Associated Press contributed to this story.