AUSTIN, Texas — May is typically Texas’ rainiest month. While the state is currently experiencing a drought, that actually increases the risk of flash flooding. Climate change is also causing more frequent and severe flooding from severe weather.

Even so, the Texas Department of Insurance reports only 14% of homeowners have a flood policy. And low-income communities of color are more often than not ending up underwater more than others.

On Frances Acuna’s street, when it rains, it pours.

“It feels like God just threw a bucket of water on us,” she said.

Acuna lives on Brassiewood Drive in the Dove Springs community of South Austin. It’s mostly Latino families, even though gentrification has driven many people out.

Catastrophic flooding happens every few years here now. That’s above average, and it’s only going to get worse.

Walking down her street, she points at homes that have water stains from the last time it flooded.

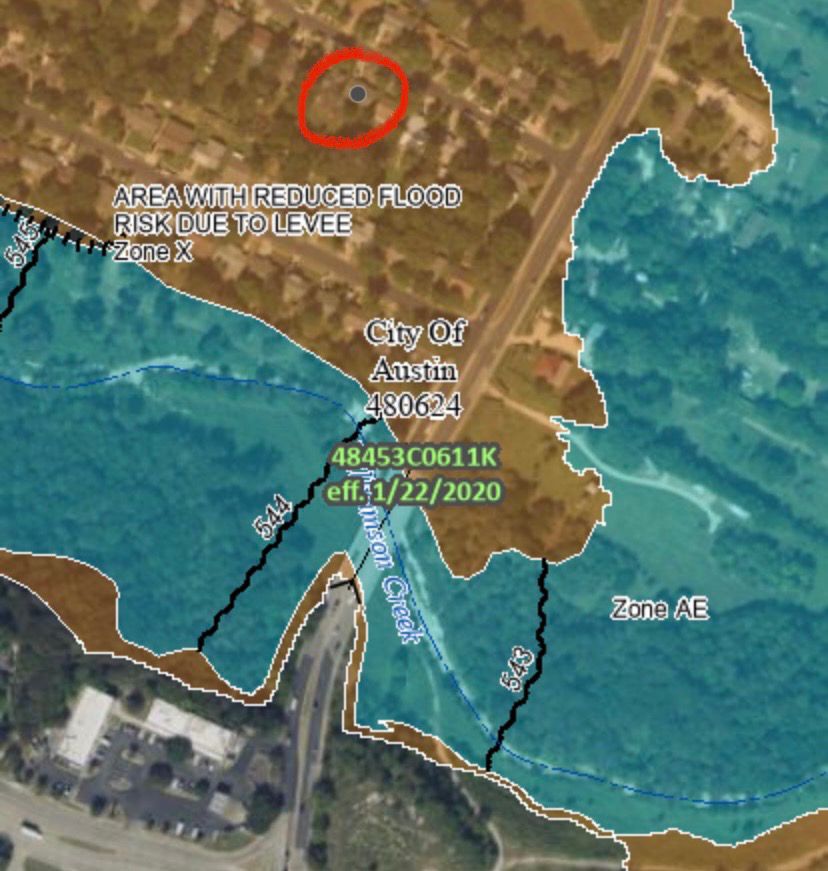

Brassiewood Drive is located along Williamson River and is not far from Onion Creek. While Williamson Creek is basically in their backyard, it’s not the because of the neighborhood’s problems. The community is more prone to localized flooding from aging infrastructure, lack of drainage and surrounding development.

“The water has nowhere to run but to the neighborhood,” Acuna said.

Directly across the street is a high-risk flood zone, according to FEMA maps, but Brassiewood Drive is not.

You can still see the damage flooding did to Acuna’s house. In her backyard, part of the concrete foundation has crumbled.

Acuna can’t afford flood insurance, and she doesn’t have the money to fix it. Her house is mainly affected by localized flooding, which doesn’t qualify for federal assistance. FEMA must declare a disaster to states and individuals to qualify for funding.

Because Acuna doesn’t live in a high-risk flood zone, her insurance is actually cheaper, but she misses out on some of the flood insurance programs and options for people who live in those areas.

“You know, we work check by check, you know we don’t have that extra money,” she said.

The City of Austin is part of the National Flood Insurance Program, which allows residents to purchase flood insurance from the federal government.

The Watershed Protection Department is currently working on a flood risk reduction project in Brassiewood, but her community is not the only one at risk in Austin.

The City of Austin Flood Plain Administrator, Kevin Shunk, says there are more than 7,000 properties in Austin that are at flood risk on the 100-year floodplain.

“All in all, we have a lot of flood risk throughout the entire city of Austin,” he said.

FEMA is also working with the city on a study in the Onion Creek Watershed which includes Dove Springs.

In 2020, the city began a five-year effort to update floodplain models and maps.

“We do have local flooding that occurs because the infrastructure does not have the capacity to convey flood waters,” Shunk said.

But this is also a statewide issue.

Texas Water Development Board (TWDB) Flood Science and Community assistant director Saul Nuccitelli says Texas has one of the highest flood fatalities in the country.

“Flooding doesn’t respect political boundaries, right?” Nuccitelli said. “Water is going [to] go where it needs to go.”

He says FEMA has limited funding to do flood risk mapping, especially localized flooding, which is more challenging. TWDB is remapping Texas’ flood risk areas to include all communities experiencing flooding.

Nuccitelli says they’ve already updated about a third of the state and plan to complete the maps by 2024.

“We’re gonna cover the whole state, map every place, even rural places like parks and whatever. We’re gonna show the flood risk everywhere.”

Flood risk areas tend to have lower property values. These areas also tend to have aging infrastructure and less green space to absorb water runoff.

Systemic racism in city development, such as redlining and segregation, also play a role in why communities of color disproportionately live near or in flood zones.

Acuna is actively working with several agencies to help communities like hers, who she says for too long have been fighting to stay afloat.

“Every year is gonna be more crucial to be ready and to, you know, weatherize your home, but how do you do it if you don’t have the means to do it?” she said.