AUSTIN, Texas — Every 10 years, U.S. census data gets an update, and so does our state and local political landscape.

Right now, maps are being redrawn to match population growth and demographic changes across the state including the 10 districts in Austin.

So why does moving lines around on a map matter and how does this vital democratic process really work?

Errol Hardin looks at maps for hours every day. He’s not a cartographer, but for him, this is a passion.

“Within those blotches are a number of life stories,” he said.

The Austinite is a volunteer commissioner with the Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission, and those blotches he’s talking about are the city’s 10 districts that the ICRC is in charge of redrawing to better align with population shifts.

“This is a unique opportunity to really participate in the process that has impact,” Hardin said.

The different colors and shapes of these district maps essentially determine what political leaders will represent each district. In this case, that would be city council members.

After commissioners like Hardin analyze these maps, they are presented at a weekly public meeting.

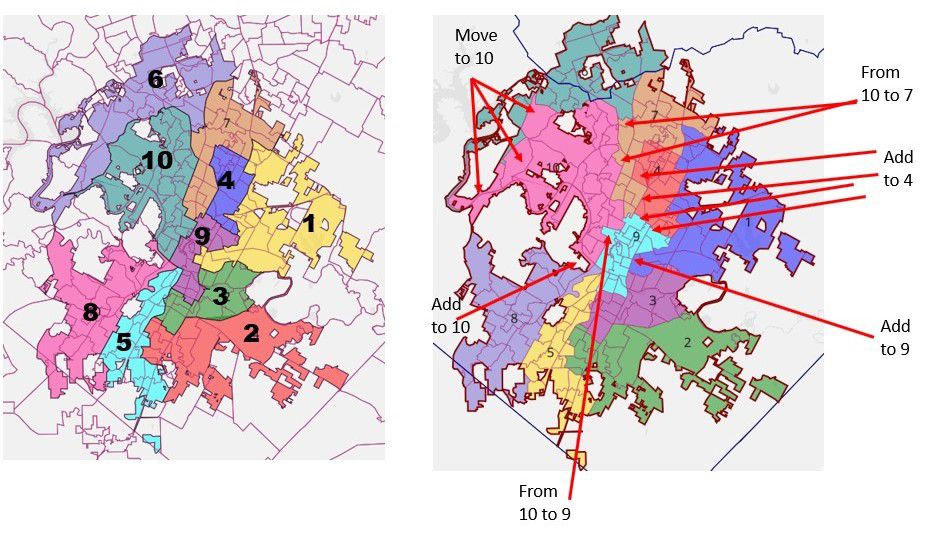

The ICRC adopted the preliminary city council district map at a public meeting Wednesday after consulting with community members and mapping experts with the NAACP and Hispanic Coalition.

When you look at the maps, it’s hard to notice the differences without someone pointing them out. The proposed changes are small shifts of tiny triangles or little squares moving from one district to another. However, the significance of minuscule moves are monumental, especially in districts with large minorities groups or “opportunity districts.”

“It’s really about human rights and voices,” Hardin said.

Gerrymandering is illegal under Austin City Code and doesn’t affect redistricting city districts since the leaders are bipartisan.

However, even the misplacement of a few lines can still be detrimental to city council representation in communities of color, which is why so much effort is put into redrawing these maps.

In District 1, the population is 22% Black, which is the largest percentage in the entire city.

“It’s an opportunity for an African American to be elected to a seat in the city council,” he said.

District 1 is Hardin’s responsibility. It’s also where he lives.

“If you look around you any of these homes are selling well over $500,000,” he said.

Walking around his neighborhood, he points out houses selling for nearly a million dollars on the market. A drastic change from 15-20 years ago.

“The fastest growing population in the city of Austin is the non-Hispanic white population,” he said.

With more white people moving in, Black people are having to move out because they can’t afford the rising prices and property taxes.

Which is why Hardin takes pride in his position: To ensure that historically underrepresented communities are accurately represented.

Hardin was born and raised in East Austin, during a time when he says everything “undesirable” was sent there.

He’s lived through segregation, redlining and gentrification, issues that are still affecting Black and brown communities today.

“When it ceases to be affordable for ethnic minorities, they have to seek housing elsewhere and then the demographic will shift such that it’s harder to have a viable intact African American community or Hispanic community that can form a voting block to ensure that you have a seat on the council,” he said.

So these maps are shaping more than just political boundaries, they’re shaping the future, and Hardin gets a front-row seat.

“I’m very passionate about doing this work so that not only Black and brown people, but all citizens of Austin have a voice at the table,” Hardin said.

There are five more public meetings and the ICRC will redraw the final map at its last meeting in October.

The map will be presented to the city council and voted on on Nov. 1.