AUSTIN, Texas — When you see a tree in your city, you might not think about the person who makes sure it’s healthy enough to stay put. In Austin, that’s Lisa Killander’s job.

As a program manager for the Forestry Division of Austin's Public Works Department, Killander evaluates trees and decides whether they need to be taken down.

“When we think about the risk of a tree, we take into account how much traffic there is. We call that ‘targets.’ How frequent are those people gathering under that tree? So the more targets, the more frequently people are under a tree, the higher the risk of that tree is,” she said. “Because a tree out in the middle of a field where nobody goes or stands, there’s no risk to that, even if it has big, dead branches, nobody’s going to get hit by that. Here, it’s a much higher risk situation.”

On the day I met Killander, her team was taking down a cottonwood tree in South Austin after a branch fell onto the sidewalk and into the street.

“The reason these trees are coming down is because even though they’re not huge, [and] they are still producing some shade, they are losing large branches,” she said. “That’s an indicator that the trees are starting to fail internally. Their system is not supporting the canopy. And it’s not safe near the sidewalk because there’s a middle school across the street.”

Killander said the tree’s location next to an office building on one side, and busy street on the other, is not conducive to a healthy, long life.

“These may have been here a long time, even before this building was put in,” she said. “I’m not sure. They may be 40, 50 years old. But they didn’t get very big, and they’re already starting to die, so that tells me they lived a stressful life. They didn’t have enough water,” she said.

Perhaps, the cottonwood would have done better near water, or in a “riparian zone.”

“We see trees in a riparian area that look so pretty and we go, ‘Oh, that would look so pretty up near my building.’ But it’s not where they have been adapted to grow. The water regime is so different,” she said.

After the trees are cut down, though, they’re used to nurture other plants.

“After they’re chipped up, they’re taken out to [Hornsby Bend] where they’re combined with municipal waste and other yard organic material that citizens contribute via the garbage pickup, and then that makes dillo dirt,” she said. “It’s a fabulous compost to put on your yard as a top dressing once or twice a year. Organic matter is what holds soil moisture and it nourishes all the soil microbes that then in turn, nourish your plants [and] make the assimilation of nutrients possible.”

“I’d always make sure that I signed in at the school so they’d know this woman ... is out walking on the campus doing this,” Killander said as she looked up and laughed. “So I’d just be standing there with my mouth open and sure enough, the resource officers, the security, would come out. Nobody told them that there’s this woman on the campus and they’d go, ‘Ma'am, excuse me. Can you show me some ID?’ They’d have their hand on their piece, and I’d go, ‘Oh man.’ I know I look like a little lost person, but arborists... we’re always [looking up].”

Texas is no stranger to extreme weather, but Austin suffered two major blows this year. After the wind and rainstorms on Memorial Day weekend, Killander took a trip to Zilker Park.

“Some of the trees looked like they were twisted by this giant hand,” she said. “They were twisted and the top was hanging down along the trunks. So that was some kind of strange wind activity going through Central Austin. What we’ve had to deal with is as many down and damaged trees as occurred during the ice storm in February.”

Killander is also still evaluating trees that never came back to life after the winter freeze. Some of the worst cases she’s seen are in South Austin. Ash trees didn’t do well there.

“I think it really encapsulates just how severe the freeze was for mature ash trees,” she said. “You know, they were already kind of hobbling along from the drought, and they were old, and they were ash trees, and they don’t live very long, but then you do like drought and then a gut punch (freeze!), and they tank.”

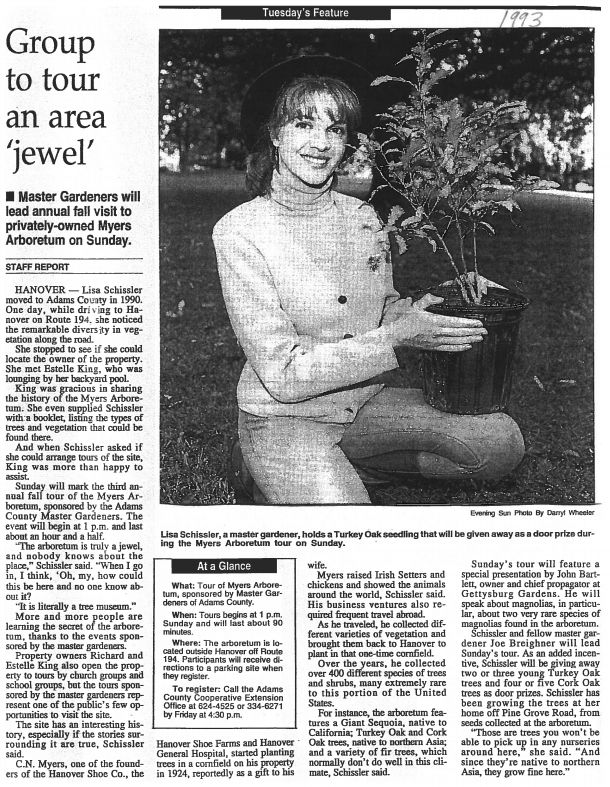

Killander studied botany in school, was a landscape designer, worked in nurseries and greenhouses, and gave tours at a private arboretum that landed her in the local paper years ago.

“I think that we are arboreal creatures, and I think that trees are part of our whole heritage from the time mankind developed on the planet," Killander said. “I think that we are arboreal creatures, and I think that trees are part of our whole heritage from the time mankind developed on the planet," Killander said.

And with every career move, she’s stayed close to her roots.

“I think when you grow up in the mountains and you’re immersed in nature, you’re imprinted with nature, and it’s just part of your being, and part of what you need and love. And the more time you spend in it, the more you just appreciate it,” she said. “I can’t tell you how much I appreciate the woods, things that haven’t been touched by man, things that haven’t been manicured and cleaned and preened.”

Speaking of pruning, Killander said it can either be the best or worst thing you do for a tree.

“I see a lot of trees in Austin that have way too much foliage removed in an effort to get light to the grass,” she said. “And I just want to tell them: The real value of your home is in your trees, not in the grass. Grass is easy to replace. So be kind to your trees, be conservative when you prune, [and] reach out to experts. The less pruning, the better.”

Back when she was giving tours at the private arboretum, Killander fondly remembers a bunch of un-pruned trees there.

“They were postos, and they were all decked out and they just came down to the ground and skirted all around the tree so that when you went inside, it was like this tree cathedral, and you could just stand there and you were totally in a room, embraced by all those branches,” Killander recalls. “We prune things up because we think, ‘The limbs are low, that’s a problem.’ No, if you stood in the sun all day, you would want to cover your whole body, right? You’d want an umbrella around you. So again, nature knows exactly what she’s doing. Those branches grow down to protect the trunk, the core of the tree. And that’s the way they should be.”

Follow Charlotte Scott on Twitter: www.twitter.com/reportsbychar