As the City of Syracuse anticipates the long-awaited revamp of I-81, for some longtime residents the process is bringing back vivid and sometimes painful memories of the highway’s original construction.

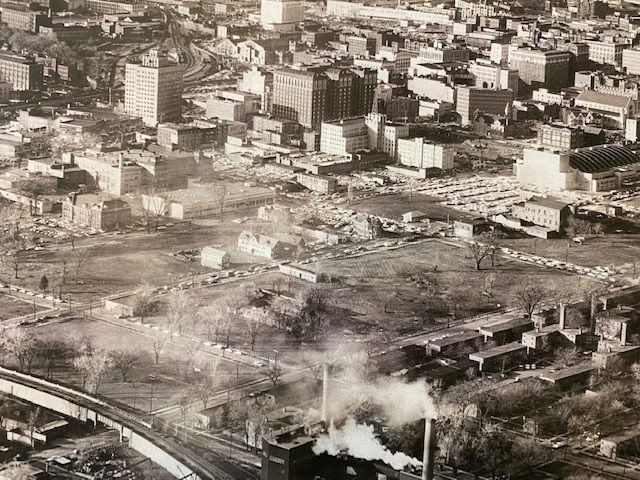

All across Upstate New York, from Albany to Rochester, highways, crisscrosses, urban areas, often literally splitting neighborhoods in two. Local historians say the construction of I-81 in Syracuse is one of the most notable examples in the country of one of these highways wiping out an entire neighborhood.

Charles Pierce-El lived it.

“I wasn’t aware of it until I became of age, to really understand what actually took place,” he said.

It’s just a short drive from Pierce-El’s current home on Elk Street, to where his childhood home stood on Almond Street between Harrison and Madison.

“We’ve got to walk down there, there’s no place to park,” he said as we walked toward where the house originally stood, emphasizing the massive change in landscape from Pierce El’s childhood memories of the neighborhood.

Once a vibrant collection of homes and businesses, the walk along Almond Street under the I-81 viaduct is a cold one on this day, the sun having no ability to reach the road surface as the interstate roars overhead.

“My house was down on the other side down here,” he said while standing at the corner of Almond and East Adams Streets. “You would have had businesses, and houses on both sides of the road. Right up to the park there.”

Pierce-El grew up in the heart of what was then Syracuse’s 15th Ward, the nerve center of the city’s black community. Also home to a sizable Jewish population and various immigrant families, it was largely demolished to make room for the highway, as well as other civic-oriented Urban Renewal projects in the 1950’s and 1960’s.

“It took away the unity that we had,” Pierce-El said of the neighborhood’s destruction. “We had a lot of unity, a lot of gardens, it took away the activities that we had.”

He says the neighborhood was wiped from the map, and argues that the process was carried out with little regard for 15th Ward residents.

“We didn’t even have a person of color on the planning board at the time, or anyone to even talk about what was going to happen to our community,” he said.

Robert Searing is curator of History at the Onondaga Historical Association. He says that while vibrant and tight knit. The 15th Ward was a community that evolved largely because Black residents had little choice as to where they could live within the city in the early 20th century.

“They were forced to live in places with substandard zone enforcement, absentee landlords, infrastructure that was aging, buildings that were built in the 1870’s,” he said. “Because of things like redlining, and things like restrictive covenants, they were literally legally prevented from buying property anywhere else.”

Decades later, as highways began popping up in American cities and Federal Urban Renewal funds were hitting municipal bank accounts, it was that same aging infrastructure that was used to make the case that the 15th Ward was the logical place to begin the city’s fight against 'urban blight.'

“Property values were way down, so when they’re building the Pennsylvania-Canada Expressway, just like they did in Boston and just like they did in Cincinnati, they’re going to put it right through those neighborhoods,” he said.

Residents were ultimately left with little choice but to relocate. Homeowners received minimal compensation for their properties, while renters were simply expected to start over somewhere else. Pierce-El says while his family was able to move out of the 15th Ward while the state was still in the surveying phase, others were forced to move to as the bulldozers fired up.

“They had to relocate, a lot went on the east side and the south side,” he said.

As the conversation shifts to the current I-81 project, Pierce-El says he is hesitant to give full approval.

“The boulevard looks great, and the renderings they have look great but then there are some problems as well,” he said.

Specifically, Pierce-El says he is concerned that the project is placing too much emphasis on access to the economic drivers in the area, and not enough on how the project will impact residents.

“What they’re proposing is more going to benefit the hospitals and the university than it is the people,” he said.

The community grid plan for I-81 in Syracuse has already faced criticism from residents for a roundabout placed too close to Dr. King Elementary School. The state agreed to move the roundabout away from the school after community pushback, but some including Pierce-El say it’s still too close to downtown and needs to be pushed further south toward I-481 and away from highly populated areas.

“It needs to be relooked at, and it needs to be changed,” he said.

Pierce-El is urging community leaders to continue listening to residents as the project continues to move forward, in part because he and thousands of others are still living with the consequences of those who didn’t.

“Our buildings are gone, the things that we had in our neighborhood, the history where I could tell my children that I grew up in that building, I played in that building. I can show them pictures, but it’s not the same as seeing it and feeling it yourself," he said.