Quinn Young, a 23-year-old Army veteran, stepped out to a podium planted amid the scrub grass. It was early fall in northeast Texas, and he and hundreds of others had just about completed a solar farm the size of 1,500 football fields.

Now, the company and local leaders were toasting him and others on the crew who once served in the military.

“I am completely mind-blown right now by how much people actually care about veterans,” Young told the small crowd.

On its face, the event was a tribute to those who once wore fatigues and now were key to the tough labor behind building the electrical farm that would generate enough energy to power more than 26,000 homes.

But something else was at play that morning—two things, actually. One was personal; a young veteran finding his footing after years of anguish; the other, far bigger—a state long associated with oil was showing the new way it would generate power.

We’ll start with the personal.

Returning home

When Young entered the Army a few years ago, he was admittedly lost. “I really didn't have anybody or anything,” he says now.

He enlisted because he ultimately wanted a better job than waiting tables. He soon found the Army provided more: structure, friendship, and lessons in perseverance.

“Things get hard and you want to give up - you’re tired, you're exhausted, you want to quit, and you just got to power through it, you've got to deal with it, just keep going forward and push. That's one big thing I took from the Army.”

But in 2019, after about three years in the military and an honorable discharge, the familiar ghosts returned – “one of the lowest moments of my life,” he calls it now.

Young was again cycling through jobs, having family issues – and struggling to find purpose.

Amid a string of dead ends, injuries to the body and a mind often reeling, he stumbled across an internet post: a construction company hiring veterans, offering free training.

First, Young thought it was a scam. Then, he clicked – “I had nothing to lose,” he said.

The firm, Adaptive Construction Solutions, was very much real and soon offered Young an apprenticeship program created by fellow Army veteran Nicholas Morgan.

They had never met before. But Morgan could already sense that he knew Young’s story. His own transition to civilian life was complicated by an injury he sustained in a roadside bombing in Iraq.

Injured or not, Morgan says returning to civilian life is never easy — a feeling familiar to many of the 200,000 service members who leave active duty each year.

“Nothing can prepare you for it,” he says.

“You can go through the best transition assistance program,” Morgan said. “But once you get on the ground, you're always going to be hit in the face.”

All the same, veterans are often prized recruits, possessing unique experiences that can easily transfer to the private sector. For one – what it takes to not complain after hours under a baking sun.

“If you've been an artilleryman, infantryman or any other occupation in the military, employers understand that this is going to be an easy transition and they know what it's going to be like,” Morgan says.

Young’s meeting with Morgan’s company led to a job with McCarthy, a major construction firm that partners with ACS to provide vets with paid apprenticeships. The company recently started building solar farms.

The hours are long, the potential for electric shock perilous. The bullsnakes will scare you. Hauling the poles that are the spines of solar farms requires concentration and teamwork.

But Young met another military veteran on the job – a “battle buddy,” who could relate. He also met a coworker and moved in with her and her young son. He’s hoping for a promotion and dreams of being a foreman.

“All you have to do is be dedicated, work hard, do what you're told, and you can make it there,” he said.

In short, his transition to civilian life was going well.

On a much larger scale, there is another change.

Gusher age to solar age

In Texas, long a landscape for oil derricks, solar panels are rising. The state’s field production of crude oil, while historically high, is below its 2020 record, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. At the same time, annual solar installations are growing in the Lone Star State – last year they were more than double what they were two years prior, per the Solar Energy Industries Association.

While the environmental appeal draws customers and investors, the motivation behind renewable projects is often simple economics. Traditional energy projects can take eight years before generating power; solar fields can rise in a year and a half, says Scott Canada, senior vice president for renewable energy at McCarthy.

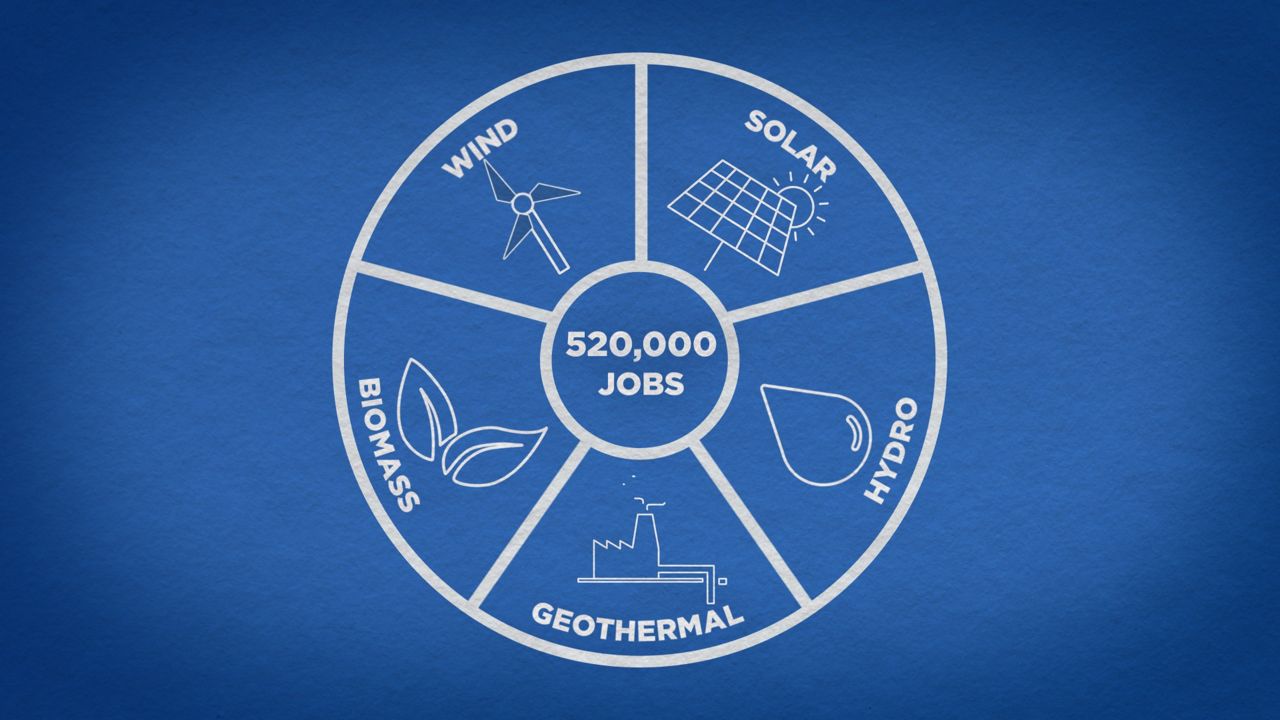

Rapid growth is changing sentiments toward renewable energy, even in areas where fossil fuels have traditionally dominated the energy industry. The job market is growing — from about 400,000 people in renewable energy positions nationally in 2016 to more than half a million now, says Amy Meyers Jaffe of the Center for Global Energy Policy, Columbia University.

By comparison, there are fewer than 40,000 people employed in coal mining and logging today.

That said, solar only accounts for four percent of power generated across the U.S., although Dan Whitten of the Solar Energy Industries Association says the goal is 30 percent by the end of the decade.

That kind of growth requires workers.

“We have 230,000 workers,” Whitten says. “We need to double that very quickly in order to meet our aspirations.”

Green energy as national security

The growth potential may make renewable energy widely appealing; veterans have a unique perspective that draws them in: their experience fighting wars, which some perceive as being rooted in the quest for oil.

“So many of our global military and diplomatic missions abroad are based on issues surrounding or stemming from our dependence on foreign fuels,” said Dan Misch, founder of the Veterans Advanced Energy Project.

Morgan is blunter: “Veterans as a whole know that we don't want our children to have to fight more wars across the globe in order to secure oil and energy,” he said.

The war in Ukraine is adding more urgency to tap domestic resources, including renewable power. Western powers are moving away from Russian fuel, leading to a spike in gas prices.

In late March, President Joe Biden announced measures to boost domestic production of fossil fuels – but also authorized the use of a national defense measure to supply materials needed for clean energy.

“We need to embrace all the tools and technologies that can help us free us from our dependence on fossil fuels and move us toward more homegrown clean energy technologies,” Biden told reporters Mar. 31

For Young, the environmental and political appeal of his job only became apparent long after he started. It was about the work, even when it’s familiarly exhausting – and regaining what he had when in uniform.

“I guess you could say it's like a brotherhood,” he said. “Everybody's a team here. Nobody's ever left alone.”