GREEN BAY, Wis. — Growing up in the lush, isolated jungles of Southeast Asia, Pao Lor said it was hard to imagine a world beyond his village.

“When you’re a little kid, everything is big. The trees are big. The mountains are big,” Lor said. “That’s all that you knew, and that’s all that you saw. You didn’t know what goes beyond the mountain that’s in front of you.”

Thinking back on that time — tucked away from the people, cities, even wars beyond the mountains — feels “surreal,” said Lor, who now lives in Kimberly, Wis., and works as a professor at UW-Green Bay.

But he’s spent a lot of time reflecting on those memories recently. Over the past few years, Lor has been working on a memoir about his childhood journey, which was published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press.

The memoir, “Modern Jungles: A Hmong Refugee’s Childhood Story of Survival,” recounts the first 14 years of Lor’s life, when he fled from his home in Laos to refugee camps in Thailand before eventually making his way to the U.S. Lor said he wanted to share insight into the Hmong American experience, one shared by nearly 50,000 people in Wisconsin, and capture some of the powerful memories from his youth.

“These memories have been playing in my head for a very long time,” Lor said.

* * *

Lor calls his personal history a “microscopic version” of the Hmong American experience: An ancient culture, a disruption, an exodus, and a shift to find a new home.

“That was kind of my world,” he said. “Being born very isolated from the world, and then one day you just go on this journey that just kept going, and going, and going, and going, and you just wonder, at some point, 'When is this going to end?'”

Like for many Hmong Americans, Lor’s journey begins in Laos, which he describes in the memoir as “ancient and isolated, beautiful, delicate, and vulnerable.”

The Hmong trace their roots to China, where they lived for thousands of years in remote areas, retaining their own unique culture. But in the 19th century, many fled from China and built new communities in the mountains of Southeast Asia — like the villages where Lor grew up, which, he writes, have since been reclaimed by the jungle.

In the late 20th century, though, the Hmong would face new and devastating challenges. As communism took hold in Laos and Vietnam, the CIA recruited Hmong people to fight communist forces in what became known as the “Secret War,” in which tens of thousands of Hmong lost their lives. And after the war, when foreign troops withdrew, Vietnamese and Laotian forces targeted the Hmong, forcing many of them to flee their villages and seek refuge.

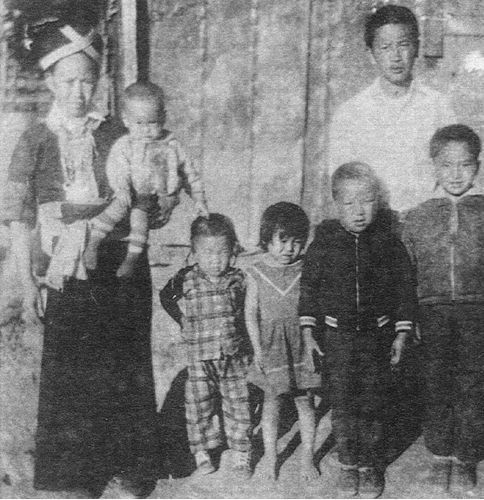

When Lor was 5 years old, he and his family joined the exodus. Though he’d later come to understand some of the bigger forces at play, at the time, he was baffled by the experience.

“For me, the only constant was just asking yourself, ‘What is going on here?’” Lor said.

The journey wasn’t easy, and not everyone from the family would survive to see the end. Lor’s father was killed after they had moved to another village, a loss that Lor said he could barely comprehend but that he felt “in its purest form.”

“It isn’t like when you’re older, and you grieve,” Lor said. “It was more just like a moment. A moment where it kicks in, where your human emotions and human instincts come into play.”

Others, including Lor’s mother and sister, were lost as the family kept moving south. But Lor and some of his siblings made it across the river into Thailand, huddled into canoes in the early morning darkness, “the sounds of gunshots echoing across the water,” he writes in his book.

Though they had reached safety in the Thai refugee camps, Lor writes that he and other Hmong still felt like “kites in a hurricane.”

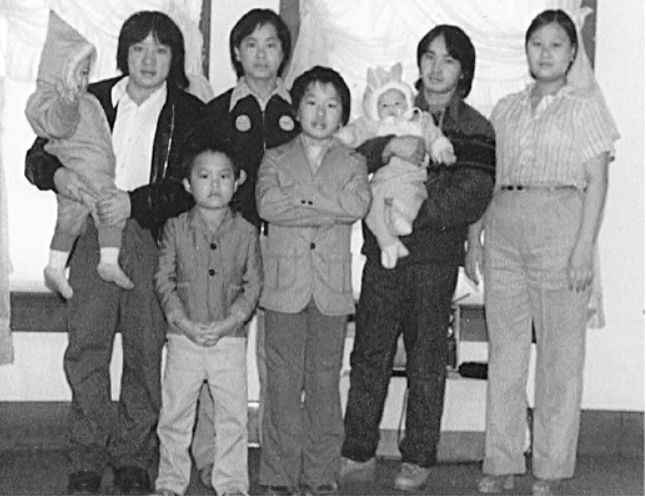

Eventually, in 1980, Lor and his family were approved for relocation to the U.S. Many Hmong refugees at this time were being resettled into the U.S., especially finding new homes in California, Minnesota, and Wisconsin.

For Lor, it was just another step on a long and disorienting journey.

“You’re living in tribal huts, then you slowly transition to these refugee camps, and then eventually, land in the middle of Los Angeles,” Lor said. “You’re going from one extreme end of civilization to the other, in a matter of a few days.”

* * *

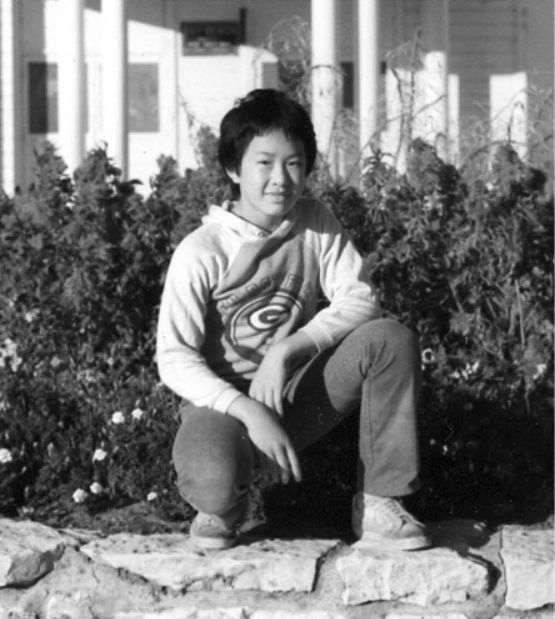

After flying across the world in the belly of the “iron eagle,” Lor and his family touched down in the U.S. They first lived in Long Beach, Calif., before moving out to Green Bay.

Living in the U.S. meant in some ways adjusting to a new mindset, Lor said — like having to think about specific dates, or understand money, after growing up in a lifestyle that didn’t rely on those concepts.

And he also faced the challenges of living as an orphan, something Lor said is “almost like a taboo in Hmong culture.”

“Without my parents, I felt like I didn’t have what other Hmong had,” Lor writes. “That I had been born out of thin air instead of into a family.”

For cities like Green Bay and Wausau, which saw rapid demographic shifts as many new Hmong residents arrived from the ‘70s on, this era was not without some friction. In his memoir, Lor recounts seeing some of the growing racial tensions firsthand, with kids on the playground or the basketball court already aware of their differences.

But, Lor pointed out, he also had to reckon with prejudices of his own. He recalled being shocked to learn that Vietnamese and Laotian kids would be enrolled in the same classes as him, after spending his childhood blaming those countries for all the horrific events he faced.

“I was like, ‘Wait a minute, weren’t these the people that we were fighting?’” Lor said. “‘Weren’t these people, you know, the ones responsible for hunting us down? The ones who caused us to leave our home, to leave our ways of life?’”

Confronting his own assumptions about other groups of people was a profound experience, Lor said. And since his early days in the U.S., he’s grown to appreciate meeting people from all walks of life.

“For me, it’s about people’s intent, and who they are as individuals,” Lor said. “You could be a Buddhist, you could be a Muslim, you could be a Christian, you could be an atheist. What I care about is your intentions, and that you use those resources for good.”

* * *

Looking back at his life now, Lor said in many ways, he feels fortunate.

“There’s a saying in the Hmong culture that each of us has a predetermined life,” Lor said. “The story goes that at the reincarnation gate, when you’re on your way to becoming a person on Earth, the gatekeeper asks you what kind of life you want to have. So it’s almost like we’re destined to do something. And I’ve always felt that.”

After the 14 years that are the focus of “Modern Jungles,” Lor went on to become the first in his Hmong clan to get his college degree, and eventually work as a teacher and administrator. He lives in Kimberly, Wis., with his wife and four kids.

In his current role, as a professor and chair of UW-Green Bay’s Professional Program in Education, Lor feels he has a responsibility to change the future as someone who is training the next generations of teachers.

Lor didn’t always plan to write a book about his experiences, though. In fact, he said, the process was pretty unexpected for him: After presenting other projects to the Wisconsin Historical Society Press, they asked him if he’d be interested in sharing his own perspective through a memoir.

Kate Thompson, the Press’s director, said her team was “honored” to share Lor’s story and bring awareness to the Hmong refugee experience, which she said has not often been told in book form.

“‘Modern Jungles’ shines a light on experiences that many of our Wisconsin neighbors have lived through but that are unfamiliar to most of us,” Thompson said in an email. “At the same time, it includes themes everyone can relate to: Coming of age, overcoming hardship, and seeking a place in the world where we feel we belong.”

Lor’s former professor and Ph.D. adviser, Clifton Conrad, said he was proud to read the “beautifully crafted” work of his former student, whom he remembers as a strong student and “lovely human being.”

For Conrad, a professor of higher education at UW-Madison, the book captured many of the qualities of its author: Humility, playfulness, authenticity, perseverance. And he said the book could have different takeaways for different audiences — serving as an eye-opening narrative for those who don’t know much about the Hmong American experience, and an inspiring story for those who have shared some of Lor’s challenges.

“There is no self-pity,” Conrad said. “He’s telling this story, and it is a sad story in many ways, but it’s also a story of resilience.”

For his part, Lor said he really wanted to capture the essence of his own memories and maintain their cultural integrity, while also making his memoir accessible to readers from all backgrounds.

In Lor’s view, we spend too much time fighting to defend our own beliefs, instead of realizing what values we have in common — like peace, and understanding, and community. Lor knows there are thousands of stories like his own out there, and said he hopes that sharing his life will help inspire or transform readers in some small way.

“I think it just comes down to people being more willing to to understand other people's experiences,” Lor said. “To be more courageous. To just be a part of other different cultural experiences. To ask, and to value that each of us simply has a different way of getting to where we're at.”