The death of George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man who was killed one year ago today by a then-Minneapolis police officer, sparked outrage across the country, including in New York. It opened a dialogue about the relationship between police, the laws they enforce and the communities they serve.

Spectrum News 1 is taking a look back at what happened to Floyd and the fallout from his death, including reform measures and mental health resources.

The battle over police reform

Watch the video for this topic

The demand for change over the way people of color are policed grew loud after people witnessed on video Floyd's death under the knee of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin on May 25, 2020. Chauvin was convicted in April on murder charges.

That movement echoed here in New York, as departments across upstate cities came face to face with protesters chanting "Black lives matter" and urging police to institute reform.

In the Capital Region, Schenectady Police Chief Eric Clifford said the calls for change after Floyd’s death led to open dialogue among residents. He was one of many top officials trying to quell tensions while managing a police department during the height of social unrest.

“What’s happened over the past year is helpful in that, now, it’s just a matter of actually forming those policies and making those changes,” Clifford said.

But in the months that followed, activists say some police departments seemed to be doubling down on the structural conditions protesters were rebelling against.

At the top of the list was a ban on all chokeholds. In July, a Schenectady police officer used a knee hold to restrain Yugeshwar Gaindarpersaud after they were called to his home to investigate a complaint.

“I said the same thing will happen, like what happened to George Floyd,” Yugeshwar's father, Jaindra Gaindarpersaud, said in a July interview.

Following that incident, the department announced it would ban all knee-to-neck restraints, but still allowed police use of knee-to-head as a control move when no other options are available.

According to longtime activist Jamaica Miles, to reform the institution of policing means to first understand the structure is systemically racist.

“I know how easily performance happens and how much harder it is to actually get action,” said Miles.

In response to mounting pressure from protesters, Gov. Andrew Cuomo issued Executive Order 203, mandating local municipalities present a plan to address equality in policing or risk losing state funding. By April 1, 2021, cities like Rochester, Ithaca, and parts of the Capital Region handed over plans aimed at more police accountability, training, transparency and funding.

However, some said plans failed to include input from the very people pleading for change.

“So after a while, if something doesn’t work, you just have to get rid of it,” said Akiva Benbow, an organizer for Troy for Black Lives.

Activists say defunding the police, such as reallocating money to other social services -- is a viable option.

“They don’t need any more funding,” Equality for Troy organizer Tascheca Medina said of police departments. “In the community, we need more education and recreational opportunities.”

Ithaca is one place that’s getting close to turning ideas like that into action. The city’s police re-imagining proposal would replace existing mobile police command units with a community solutions and public safety team.

“Right now, there's obviously a lack of trust between the police and the community, and we need a significant amount of communication and common ground finding to move forward,” said Ducson Nguyen, an Ithaca alderperson representing the city's Second Ward.

In Albany, officials said police reform started with the repeal of law 50a passed by the state Senate over the summer. The law mandates police misconduct records be made accessible to the public.

“If we are talking about reform, it’s one, addressing the things that are happening right in front of you, and then moving forward listening to the community,” said Paul Collins-Hackett, a member of the Albany Civilian Police Review Board.

Albany, like other cities in upstate New York, has had its own high-profile cases that have led to calls for change.

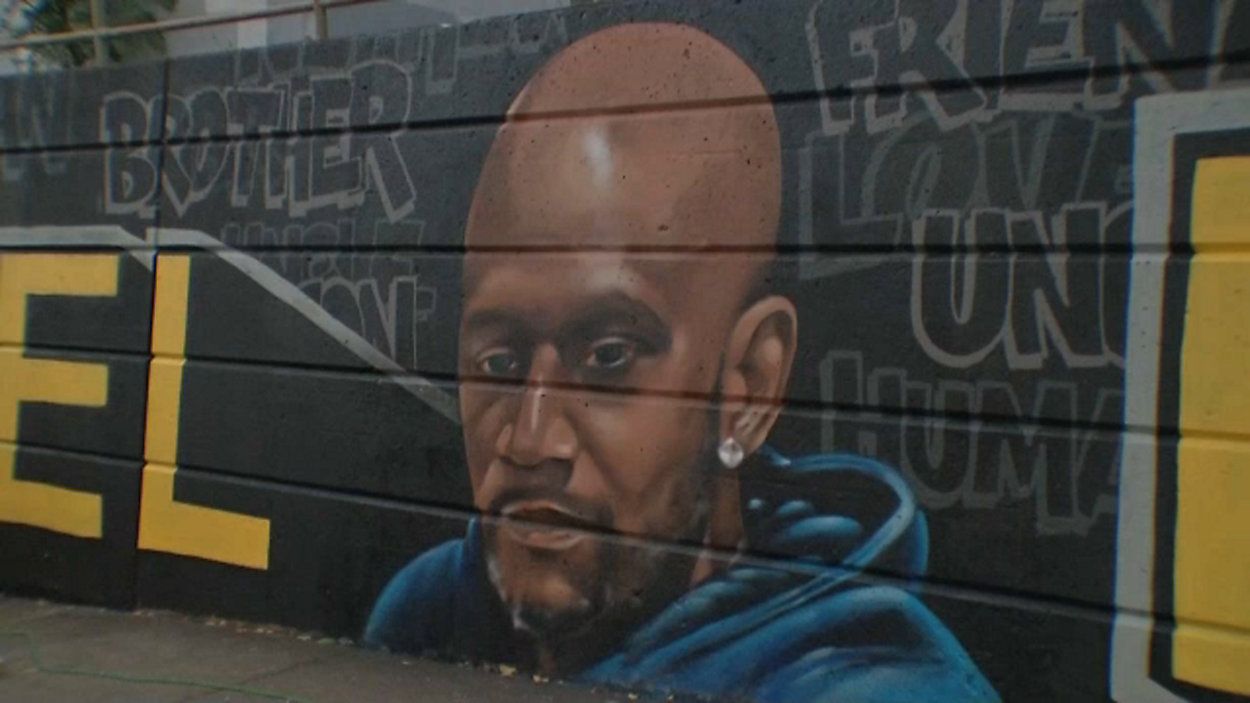

Dontay Ivy, 39, was an unarmed Black who died in 2015 during a confrontation with Albany police. Officers tackled and used a stun gun on him after believing he was acting suspiciously and carrying a gun, police said at the time. His death was ruled a homicide, but an Albany grand jury declined to hand up charges against the officers involved.

In 2018, a police detective said his life was in imminent danger when he fired two shots at 19-year-old Ellazar Williams, who was paralyzed as a result. The officer was cleared of wrongdoing by a grand jury, and the county district attorney declined to file charges.

“It’s those cases that reinforce the national narrative on a local level,” Collins-Hackett said.

And while those fighting for social justice have seen some steps toward reform, like the conviction of Chauvin for the death of George Floyd, others feel the past year has shed light on the work that still needs to be done to achieve true equality for people of color everywhere.

“At the end of the day when the smoke clears and everybody is done, No! I’m not done, I’m still going to be looking for change,” said Medina.

Debate on demilitarization and defunding the police

Watch the video for this topic

In an encounter last June, Buffalo police in riot gear moved forward in formation attempting to enforce a curfew during a Black Lives Matter protest. One of the officers shoved protester Martin Gugino. He hit the ground, suffering a severe head injury.

Gugino has since recovered, and a grand jury chose not to indict the officers, but the incident became yet another flashpoint in the national conversation on the militarization of police departments.

"We certainly did try to address it,” Buffalo Mayor Byron Brown said.

City leaders disciplined three of the officers who were part of the Emergency Response Team – the unit formed to respond to civil unrest. In response, all 57 members of the ERT quit, but didn’t resign from the force. The city later disbanded the ERT.

"The Buffalo Police are prepared in instances like that, but we want to also make sure that when individuals want to protest, if they want support, if they need support, that we have trained people who they can reach out to, who they can talk to, to make sure protest activity is safe and protected in the city of Buffalo,” Brown said.

Militarization of the police is loosely defined as tactics and equipment that are usually seen on the field of battle, rather than on a city’s streets. But the term can vary based on who’s involved.

Last year, the Ulster County sheriff and county executive penned opposing op-eds on the federal 1033 program, which transfers surplus military equipment to law enforcement for free.

County Executive Pat Ryan says the militarization issue became clear as he walked in a protest and approached a wall of officers in full tactical riot gear.

"I know instinctively that protesters need to be protected, too,” Ryan said, “and that there needs to be some safety and security at any events and gathering, but to me, what I saw just felt out of sync."

When it comes to the equipment, Ulster County received a mine-resistant ambush protective, or MRAP, vehicle through the 1033 program. Sheriff Juan Figueroa pushed back against calls to remove it from the fleet.

"If there's a school shooting, we can go right up to the school and evacuate people,” Figueroa said. “We have zero vehicles that are bulletproof in our fleet except for that vehicle."

An idea gaining traction around the state and nationally is reducing and re-training the officers of police departments. For example, in Rochester, Mayor Lovely Warren says reforms are coming.

"We aim to reduce RPD personnel within the next five to 10 years so we can reallocate those resources to other programs,” Warren said.

Back in Buffalo, Brown says demilitarization and so-called defunding can go hand in hand.

"There are other things that we can do preventatively that require funding, and so we want to allocate funding to things that can stop a crime or stop someone from moving in a criminal direction even before a crime occurs,” Brown said.

He says it's not necessarily about taking money away from the force, but reassessing priorities and allocations.

The mental health 'awakening'

Watch the video for this topic

Floyd's death highlighted the need for mental health services. City, state and community leaders are looking into whether police are adequately equipped to handle non-life threatening mental health calls – and who should handle them in the first place.

“Our system, our public safety system was built with really just two places in mind, the hospital or jail,” said Rochester Recreation and Human Services Commissioner Daniel Lyman-Torres.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, people suffering from a mental condition are booked into jails about 2 million times each year. Over the past five years, of the people police shot and killed, nearly one in four had a mental health condition.

Some cities like Rochester see the problem and are trying to find solutions.

“Growing up in my community, I dealt with, personally, a lot of the issues that our clients are dealing with now,” said Dre’ Johnson, an emergency response social worker. “And so when the opportunity presented itself to join a pilot program like this, I had to jump at that opportunity.”

Johnson is part of Rochester’s person-in-crisis team – a pilot program aimed at responding to mental health, substance abuse and similar calls. Johnson and a partner respond to mental health calls that come through 911 or 211, sometimes on their own and sometimes with police.

“A lot of them [police officers] are really glad when we get to the scene because you don’t sign up to be a police officer to deal with mental health abuse,” Johnson said.

Last year, the police in Rochester repeatedly came under fire for alleged use of excessive force and lack of empathy. Still reeling from the Floyd case, the community learned the details surrounding the death of Daniel Prude, a Black man who died following an encounter with police when Prude was both naked and distraught.

In February, police body camera captured a 9-year-old girl being pepper sprayed by Rochester police officers as they tried to strong-arm the child in a squad car.

One month later, police shot and killed a knife-wielding man charging at them in front of a homeless shelter.

These cases and others, officials say, involve individuals in the midst of mental health and/or substance abuse crises, and police themselves are asking for more training, assistance on mental health calls and support from local leaders.

"We know that throughout the country, other cities are looking ... and saying, ‘how can we create a community based solution, a way to keep people getting the right resources at the right time and do things differently when it comes to public safety?’ " Lyman-Torres said. “So that's why the person in crisis team was developed, to be first responders in the public safety system for people who are in crisis.”

Johnson says most of his calls are for public intoxication, domestic issues or suicide threats – problems they’re trained to handle in a way traditional cops are not.

“We want to help people get to that prevention piece, before they end up requiring hospitalization or before there's any kind of crime committed or some kind of interaction with law enforcement that could be staved off, if there's a community based resource,” Lyman-Torres said.

Lyman-Torres said she believes this program is one-of-a-kind, and she’s been contacted by other cities and her Canadian counterparts asking for more information.

“I would say that this is the beginning of an awakening,” Lyman-Torres said. “This is the beginning of an awakening for how we treat people with mental health issues and substance abuse issues … this is not the end; this is the beginning, and it is an awakening about what's going on in our country with mental health.”

'We’re not sitting back and taking this'

Watch the video for this topic

This is not the first time the nation has seen an uprising with demand for change. Similar calls came after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968 and the acquittal of police officers filmed beating Rodney King at a traffic stop in Los Angeles in 1991. But many say the protests that have taken place over the past year is not just a moment, but a movement of young and old that won’t stop their activism until substantive changes are made.

For many, the verdict read in a Minneapolis courtroom on April 20, 2021, finding Chauvin guilty of Floyd’s murder, brought a sigh of relief. The conviction meant to many Americans that accountability for one is not the same as justice for all.

“I think it’s important how we celebrate this moment,” said Yusuf Abdul-Qadir of the NYCLU. “I think we have to be careful about how we talk about this moment.”

Jurors reached the guilty verdict in 10 hours, but the road that led to it was long, and the people walking it were unrelenting in their pursuit.

Following Floyd’s death, a group called Last Chance for Change was born in Syracuse.

Led by several young and newer activists, Hashan Bloodworth’s voice led every march as they walked through the streets day after day.

“I came with a megaphone the first day,” Bloodworth said, “and then one [day] I came with a microphone and a speaker, so that everyone would be able to hear the message that I had.”

The group demonstrated for 40 days. As the summer of 2020 went on, Bloodworth and others saw a need for more hands-on activism. He then co-created Rebirth SYR, a group that would appear all over the city – at vigils, crime scenes and memorials.

A father, a brother and an activist, Bloodworth now devotes nearly all of his life to activism, because he says he’s witnessed the mistreatment of his own family and community.

“Just imagine your child on the pavement, face down with a knee on his neck until he has no breath left in his body,” he said. “Imagine that for five, 10, maybe two minutes. Imagine that, and tell me how you feel.”

Curtis Chaplin was one of many Last Chance for Change leaders. Like Bloodworth, Chaplin felt the community needed something different, something more than protesting alone. Now he devotes his time to youth.

“Our generation is different. We’re not sitting back and taking this,” Chaplin said. “We deserve better. After so many times of asking, we are going to force you guys to give us better.”

Calls for police reform and demands to end racial inequalities and restore fundamental human rights came from people of all ages.

The Pew Research Center found that 41% of all Americans attending protests in June 2020 were between the ages of 18 and 29. And according to Pew, 59% of the people protesting last year were 30 or older, many already members of groups like National Action Network and SPAARC, the Syracuse Police Accountability and Reform Coalition.

Abdul-Qadir, a lead organizer of SPAARC, has advocated for social justice issues for 16 years.

“Change is very difficult and hard fought,” Abdul-Qadir said. “And as you disrupt the system, the system pushes back as hard as you’re pushing. In many respects, you’ll find it is a marathon mixed with a relay race where you’re running that race, but you have to pass that baton on, but the race is a marathon.”

By mid-summer 2020, SPAARC and other groups formed a coalition presenting the city with nine demands. The People’s Agenda for Policing called for changes such as removing resource officers from schools, reallocating money from the police department’s budget to other Syracuse resources, and giving the citizen review board the power to discipline officers.

None made it into the city’s final reform plan. SPAARC continues to fight for the city to adopt the agenda.

The past year is proof that the road to change is sometimes narrow or unpaved.

“It is not for the lighthearted,” Bloodworth said.

A community conversation calls for change

Watch the video for this topic

Barbershops offer a lot more than just a haircut. It's an environment where healthy conversations can often be exchanged. And since the death of Floyd, a barbershop in Rochester found its customers sharing their ideas about police reform and justice.

It’s a place where the world’s problems aren’t always solved – but they try.

The anniversary of Floyd’s death prompted one conversation.

“As a Black male, it was, I hate to say shocking, because you see it every week pretty much now,” Dexter Craig said.

“It makes you feel angry. It makes you feel hurt,” Thurston Johnson said.

It’s an uncomfortable conversation, but one that has to happen. Floyd’s death brought conversations on race — and policing — to the forefront.

“OK, somebody took a blunt out of a store or somebody's resisting arrest, but it doesn't ... They don't deserve to get murdered for that. You know what I mean?” Karim Curtis said. “That’s your job, to know how to de-escalate someone who’s resisting arrest.”

Two months before Floyd died in Minnesota, there was another case in Rochester just six blocks down the street from the barbershop.

“It's kind of weird that it happened in March, and then we didn't hear about it until months later. That’s what got me,” William Morgan said of the death of Daniel Prude.

In February, a grand jury declined to indict any of the officers involved in the police call that resulted in Prude’s death.

“We suffer a lot of pain,” Johnson said. “We suffered pain with Daniel Prude; that was pain we suffered, all of us. Even if we didn't know him, we still felt that.”

“You're taught that justice is blind, and it's, you know, the scales are balanced. But when it comes to us, people of color, Black and brown, seems like that scale is always tipped,” Craig said.

It’s a perspective that, if not lived, might seem hard to fathom.

“This is nothing new,” Willie Lightfoot said. “The pain is so deep because of the end of the day it's nothing new.”

Real change takes action, but it’s obvious that there’s a long way to go.

“Poor white people in America, in the country, won't even join arms with Black people in the movement of fighting the social part, and the economic part,” Curtis said.

But the conversation is happening, and that’s reason enough for hope.

“I just pray, and I know change is about to come about in all cities,” Johnson said.

This story was reported and written by Mercedes Williams, Ryan Whalen, Wendy Wright, Katelynn Ulrich and Seth Voorhees. Video by Muneib Chater.