Spectrum News is investigating the handling of mental health calls by local law enforcement. If you or someone you know with a mental health condition has had any interaction with Buffalo Police Department and would like to share your story, please email me at Camalot.Todd@Charter.com. Thank you.

BUFFALO, N.Y. — On September 12, Buffalo Police Department (BPD) Officer Karl Schultz shot 60-year-old Willie Henley during a mental health call after he allegedly struck an officer with a bat.

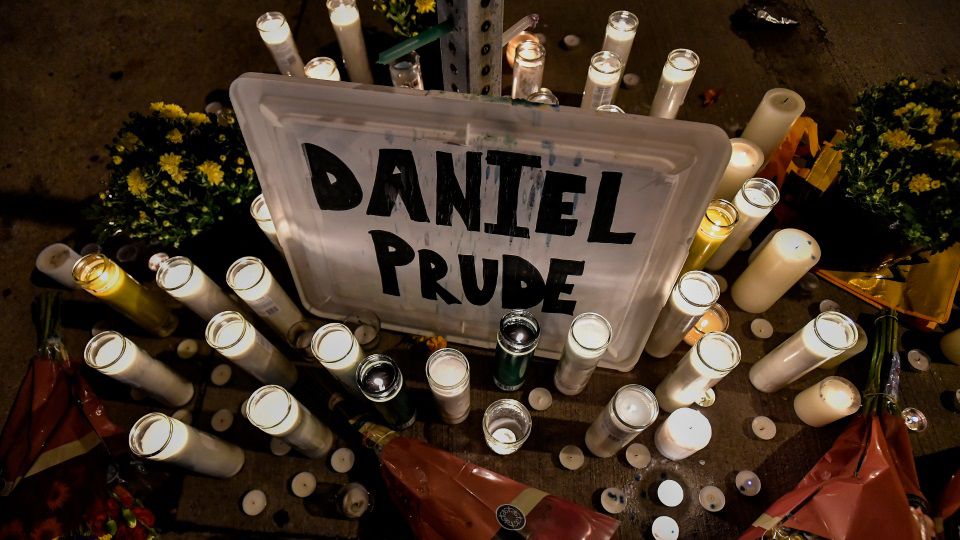

In March, Rochester police officers responded to a mental health call by Daniel Prude’s brother. Prude, a 41-year-old Black man, was pinned to the pavement and lost consciousness during the restraint. Prude later died, and an autopsy ruled his death as a homicide, according to the Democrat and Chronicle.

It is at least the third incident in Western New York where a mental health call to the police escalated — all of which involved Black New Yorkers being harassed by white police officers.

“As a result of deinstitutionalization, police have been the primary responders for those suffering from mental illness. While not all individuals are violent, police are called due to an increased level of aggression or agitation by family members or the community,” said Buffalo Police Department Captain Amber Beyer.

Deinstitutionalization, a government policy starting in the 1960s that shuttered large psychiatric hospitals and moved people with mental health needs to community resources, was supposed to better serve people without isolation.

But because of decades of cuts to those community mental health programs, law enforcement became the de-facto providers of behavioral health care, not just in Western New York, but the nation.

The intersection of race and disability can have violent outcomes for Black Americans like Prude or Henley.

When an individual calls the police for someone who is in a mental health crisis, officers must assess whether that person is a threat to themselves or others.

But how that judgment is made needs to be done in a very careful way, said Amy Watson, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Social Work Department professor who studies law enforcement and mental health.

“We really need to be careful on how we’re judging dangerousness because we’re just going to reinforce racial inequities,” she said. “If there is bias involved in our assessment of dangerousness, we’re really not going to move the needle too much on addressing these horrible things that happen when police are involved with a person of color who is having a mental health crisis.”

Complying with police officers' commands, something that could de-escalate situations, is inherently challenging for those who are in psychosis, a heightened sense of anxiety or trauma.

“Once police are out there — it’s very frightening, it makes people feel very vulnerable, it’s very stigmatizing and it doesn’t actually provide the appropriate response,” Watson said.

Improvements have been made by local law enforcement on how they handle these calls. There are currently 128 BPD officers who took Crisis Intervention Training (CIT) through Crisis Services, said Beyer.

Additionally, Buffalo Mayor Byron Brown announced a BPD Behavioral Health Team, which will consist of six trained officers, two lieutenants, three clinicians and a program supervisor, which will help law enforcement respond to mental health calls.

Crisis Services operates a 24-hour, 7-day hotline at 716-834-3131, supportive services for families in crisis through their established Mobile Outreach Program and or visit their website for more information.