The bulk of Western New York’s mental health services are in Erie County, but the closing of in-unit psychiatric beds in other rural areas like Chautauqua County, lack of transportation, and getting insurance leaves more people forgoing care, according to a report from the Milliman, actuarial firm company for health care, commissioned by Mental Health Treatment and Research Institute.

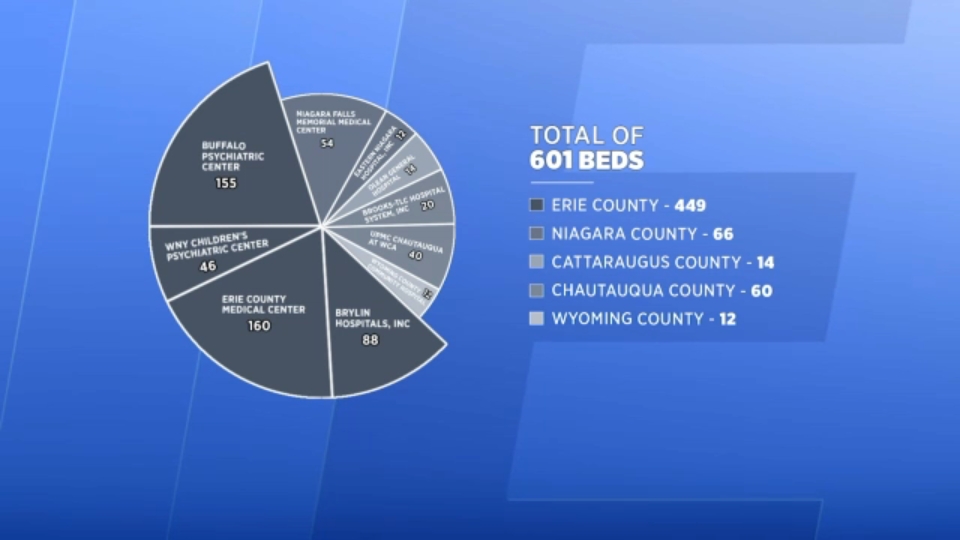

Of the 601 in-patient psychiatric beds licensed by the New York State Office of Mental Health in Western New York's eight counties, more than two-thirds are located in Erie County.

The largest provider, Erie County Medical Center, is licensed for 160 beds. BryLin, the only private hospital licensed for in-patient psychiatric beds, has 88.

Those two hospitals make up just under half of all licensed in-patient psychiatric beds for a population of almost 1.6 million people.

ECMC Comprehensive Psychiatric Emergency Program (CPEP) is often the busiest one in New York state, said Dr. Michael Cummings, the associate medical director for Behavioral Health Services at ECMC.

"A lot of people don't realize that our psychiatric ward, or our CPEP...is the busiest one in New York state,” Cummings said. “Every once in a while, Bellevue, Manhattan sees more patients, but we were literally the busiest psych [emergency department] in the state."

ECMC psychiatric emergency room is also one of the only services outside of the Erie County Holding Center that is open 24/7 to provide mental health care treatment.

But CPEP is often used as a place for mental health treatment by people with less intensive needs or social issues like homelessness.

"One of our biggest challenges is trying to have a psychiatric emergency room be utilized for what it's built for, which is someone in a psychiatric crisis,” Cummings said. “It's a larger challenge when it's someone in a more social crisis, that has manifested slightly in a psychiatric manner or sometimes not at all, but they still come to our emergency room."

The CPEP is often used to address social determinants of health, like not having enough food, safe housing, or by those who are homeless, or those whose mental illness overlap with the criminal justice system, Cummings said.

If an individual who is in a crisis interacts with law enforcement, officers can take them to CPEP through an involuntary transport under section 9.41 of the New York state’s Mental Hygiene Law.

In 2013, the ECMC CPEP was experiencing overcrowding due to the 9.41 transports, according to Tracie Bussi, the director of emergency mental health response services at the nonprofit Crisis Services.

Crisis Services have helped reduce the 9.41 transports to CPEP with their crisis intervention training for law enforcement in the area, but after measuring effectiveness early on of the program the nonprofit stopped pulling the date, according to Bussi.

But access to mental health treatments in the community — and outside of law enforcement — is becoming harder especially in rural counties — three counties, Allegany, Genesee and Orleans, have no licensed beds.

Brooks-TLC Hospital System in Chautauqua County plans to shutter its 20 psychiatric beds on January 1, bringing that county's total to 40.

Dr. Brian Joseph, a medical director at BryLin Hospital, cites the cost of operating these beds as a major reason why they end up closing — especially for beds that rely on funding by the state and local governments.

"As a society, we'll live with kids who are damaged, we will live with people living on the streets,” Joseph said. “We don't want to pay more money."

That hospital isn’t the only place where in-unit hospital beds for mental health are in danger of closing, according to Joseph.

"The state hospital has been trying to cut back on beds, which makes it more difficult for the seriously, chronically and persistently mentally ill to find inpatient care when they needed as opposed to living on the street or ending up in jails,” he said.

The Buffalo Psychiatric Center, a state-run facility, operates 155 state-licensed beds, the second-largest provider in Western New York behind ECMC.

Not only are there fewer places for those with severe mental illness to go for treatment, but there are also fewer places that accept their insurance.

Over a quarter of people with severe mental illness get their coverage through Medicaid, the single largest payer for mental health and substance abuse treatment in the country.

But, there’s a shortage of providers accepting Medicaid, inadequate services and transportation barriers.

"There are issues when it comes to coverage related to insurance for mental health and impacts mental health providers,” Republican Senator Robert Ortt said. “But it also impacts those who are seeking services."

The closing of beds and providers not accepting Medicaid for mental health treatment are leading more people with severe mental illness to go untreated — until they encounter law enforcement.

That’s when nearly one-third of those individuals have their first contact with mental health treatment and they’re incarcerated at higher rates, according to a U.S. Department of Justice report.

Half of all suicides in jails and prisons are committed by those who are seriously mentally ill, according to a Treatment Advocacy Center report.

"You expect hospitals to be a certain kind of place,” Joseph said. “And a jail is not a hospital no matter what quality of professionals they have working there."

Possible Solutions:

Contact your local officials to improve access to social determinants of health like affordable housing, insurance and food can prevent people using the ECMC CPEP for other reasons.

Advocate for local officials to look at other places to create new and innovative approaches to law enforcement interacting with those with mental health conditions similar to Texas’ Mental Health Deputy programs.

The final story in our series “Navigating The System” airs tomorrow at 6 and 11 p.m. It dives into some of the innovative ways that Buffalo City Court addresses those who have mental health conditions that find themselves involved with the criminal justice system.