June is Pride Month, which is often associated with bright colors, loud pop music, and glittery parade floats traveling the streets of cities across the country -- but it wasn’t always this way.

The first Pride started because of The Stonewall Riots in 1969. Two transwomen of color, Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, led the way, starting an uprising when police raided the Stonewall Inn and Tavern.

This fight against police brutality is known to be the start of the Gay Liberation Movement. Nearly 400 miles away on the other side of the state, a community of activists in Buffalo forged their own path in the fight for LGBTQ equality.

“People don't recognize it, but Buffalo is very much a trailblazer of the early gay rights movement,” said Adrienne Hill, one of the cofounders of the Buffalo- Niagara LGBTQ History Project. The group is made up of volunteers working to document and celebrate the vibrant history of the LGBTQ community in Western New York.

Hill said that while New York City and the San Francisco Bay area are well known for their histories of LGBTQ activism, smaller cities were, and remain, just as critical to the movement because they can rely on a sense of community to help push along progress.

“Buffalo is a hometown. It's a relatively small city. Most of the people who live here, not only have they lived here their whole lives, but generations of their family have lived here and so there's a lot of deeply embedded relationships,” Hill explained.

These relationships play a driving force in local activism, Hill said, which differentiates small-city LGBTQ history from the larger ones. With that said, there are several historical events that happened in Buffalo that are similar to what happened at Stonewall.

The history of Buffalo’s gay liberation movement is extensive. Hill noted that in the 1940s and 50s, the city had a well-established gay bar culture that tended to be left alone by police due to corruption. When Nelson Rockefeller was elected governor of New York State, there was new pressure to crack down on police corruption. In turn, law enforcement began to crack down on the gay and lesbian bars throughout the 1960s. In an effort to push more Western New Yorkers to live in the suburbs and commute downtown, many of these LGBTQ spaces were destroyed and turned into parking lots that are still used for commuters in Buffalo to this day. Hill explains that this time was even worse for black-owned bars.

“There was a difference between how the predominantly white bars were treated and how the predominantly black [bars were] treated,” Hill said. The majority of the black bars and spaces of the time were located on Cherry Street, which runs immediately parallel to the Kensington Expressway. “In essence an expressway was built right through the heart of the black lesbian neighborhood,” Hill explained.

In November 1969, one of the last gay spaces, The Tiki on Franklin and Tupper, was shut down. This is the current location of another parking lot. The owner of The Tiki, James Garrow, was denied by the New York State Liquor Authority because he was arrested for allegedly cruising other men, which refers to secretly looking for other men as partners.

Hill says the next month, The Avenue, located where the Frank Sedita City Court building, was opened. He was denied again for a liquor license, so the Avenue became a gay “juice bar” and an underground center for LGBTQ people to meet.

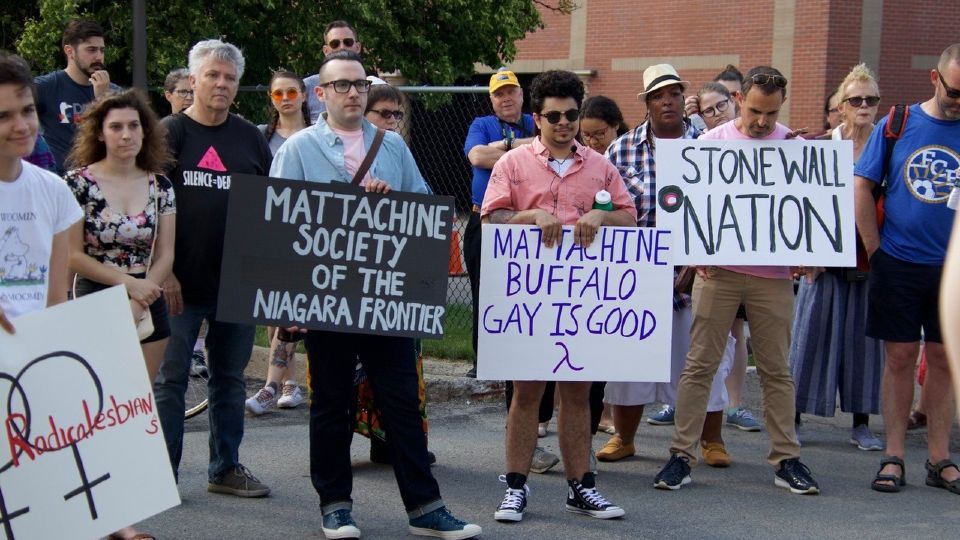

It was here that the Mattachine Society of the Niagara Frontier was organized, Buffalo’s first gay rights organization.

Officers were furious that this was happening “right under their noses.” On January 4, 1970, according to Hill, The Avenue was raided, where 94 people were kicked out of the bar, 11 arrested, and two lesbians were said to have been beaten up by officers. Hill said this really lit the fire for the movement out of Buffalo. The raids and the bar scene are documented in activist Madeline Davis’s book, “Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold.”

Hill said that it’s important to look at our roots so that the modern generation can learn how to be better activists moving forward. “The fight for social justice happens year round...history is not just about celebrating our past. I think history is a way to study our past and to find out what activist tactics that work in this particular area and what has not.”

One of those modern activists is Camille Hopkins. She was the first employee at Buffalo City Hall to transition from male to female -- and was a driving force behind the push for anti-discrimination laws regarding fair housing. She has spent years fighting for the rights of LGBTQ people, and helped Spectrum Transgender Group of Western New York -- what she calls a thriving support group.

Hopkins said that while there has been progress over time, she feels that Buffalo still has a long way to go, especially when it comes to racism and homophobia. “If a person is racist, in all likelihood they're homophobic … and I'm concerned about my safety. To tell you the truth, every time I go out, I'm constantly looking around.”

Despite her fears, Hopkins said she has hope that the younger generation of activists will fight for not only LGBTQ equality, but also continue to fight against racial injustices. She also hopes that younger people will vote, which she thinks is something that previous generations have done well. “There's no perfect candidate. Sometimes it's a compromise... but let's get the best we can in any kind of compromise So kids, register and vote. It's one way to make your voice heard. And when your voice isn't heard, then lobby and demonstrate.”

To get in contact with the Buffalo-Niagara LGBTQ History Project, you can contact them on Facebook or on Instagram. There are several projects within the group that provide volunteer opportunities. Hill said they are working on turning the project’s walking tours virtual during the pandemic.

Another project in the works is a documentary about Buffalo’s black LGBTQ performance and the Ball Scene. Anyone looking to donate to the LGBTQ History Project can do so by starting a fundraiser on Facebook.

Throughout Pride Month, Spectrum News will continue to provide you with voices from across the Western New York LGBTQ community, focusing on navigating Pride Month during a global pandemic and a time of national protests, and what it truly means to be part of the LGBTQ community.

To view Part II of this online series, click here.