BUFFALO, N.Y. — Alcohol use disorder can wreak havoc on a person's life.

A recent study found that between 2015 and 2019, it led to 232 million missed workdays in the U.S. annually. The pandemic just made things worse.

Everyone has a story.

“We coach. We don’t counsel,” said Ted Bodensteiner, a recovery coach with Save The Michaels of the World, a nonprofit located in Western New York.

It’s in Bodensteiner’s office that people can make the choice to start a new chapter.

“If I give you the answers, or what I think you should do, you're more than likely not going do it or it's not going work for you,” Bodensteiner said.

He works with people dealing with substance use disorders and sees the toll it takes on every part of their life, especially employment.

“People at work, probably sense there's something wrong with you," Bodensteiner said. "You're either late or you're coming up with excuses as to why you're not there. You're 'sick' a lot."

The study found about 14% of all missed workdays in the U.S. among full-time workers come from those with drinking disorders, even though that group of people only makes up about 9% of the population.

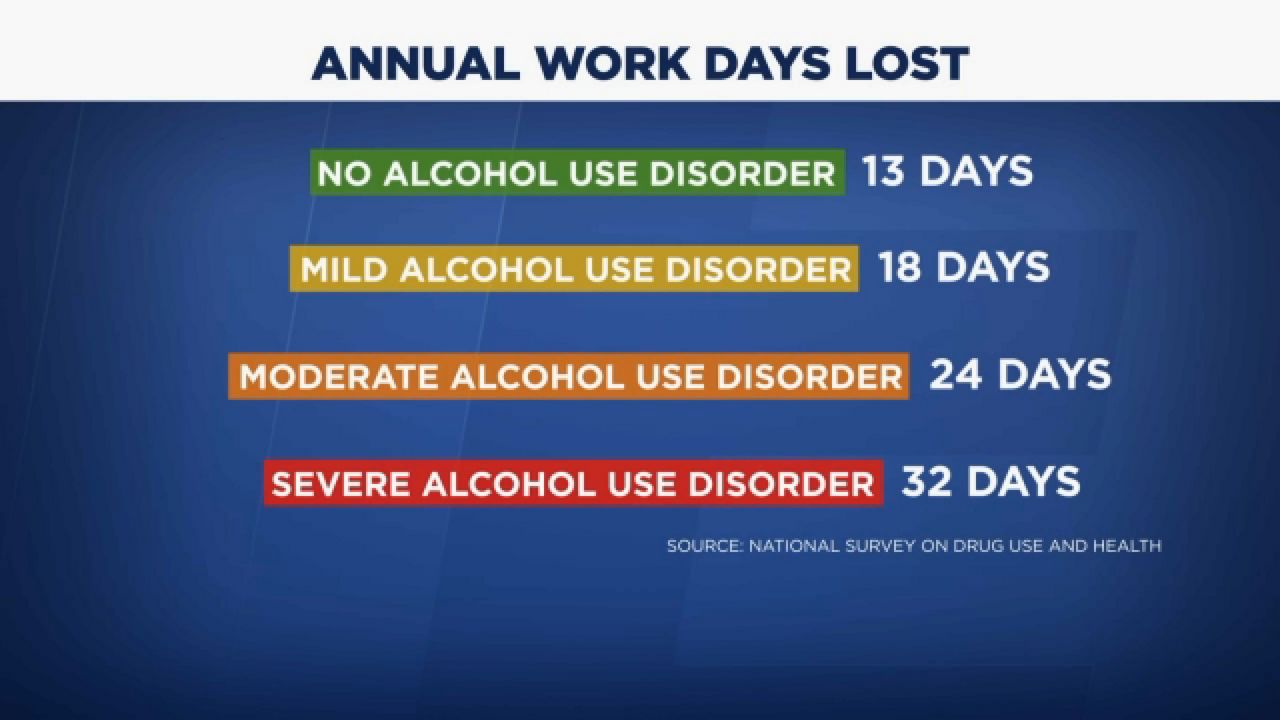

People with no disorder miss about 13 days of work per year. Those with mild disorder miss 18 days, moderate — 24 days, and those with severe alcohol use disorder miss 32 days. It's more than double that of those with no disorder.

“I don't think it's a conversation that we like having at work. Because I mean, for obvious reasons...it's embarrassing,” Bodensteiner said.

It's a tale he knows well.

“That's the license plate of the car I drove from Nebraska to here and I don't remember driving here about five years ago when I was an active user,” he said, pointing to a license plate on his wall that serves as a reminder of the challenges he overcame.

He’s been sober for four years now, but before then, he lost multiple jobs because of his addiction, even one as a rehab counselor.

“I think they knew I was struggling and they gave me a couple chances," he said. "But I didn't feel safe. I didn't feel comfortable telling everybody what was really going on because I figured it was career suicide.”

The researchers behind the study hope it shows how the workplace can be a point of intervention, not one of no return, which can be a setting that can offer time away from work and support.

“We're trying to change the conversation and make it such that people realize this is a disease," Bodensteiner said. "It's not a choice. It's not a moral problem. And it's okay to go seek help."

He didn’t get that chance.

“They didn't really offer me any resources," he said of the rehab facility at which he worked. "They're just like, 'get it together,' and I was like, 'Um, ok.'”

While you have to want to turn the page on substance abuse, a helping hand never hurt.

“It may have changed things, it may have," Bodensteiner said. "It may have given me the ability to say okay, I really do need to take care of this and there are people that care."

Absences among those with an alcohol use disorder were higher among men, younger people, those with lower incomes and white or Hispanic populations.