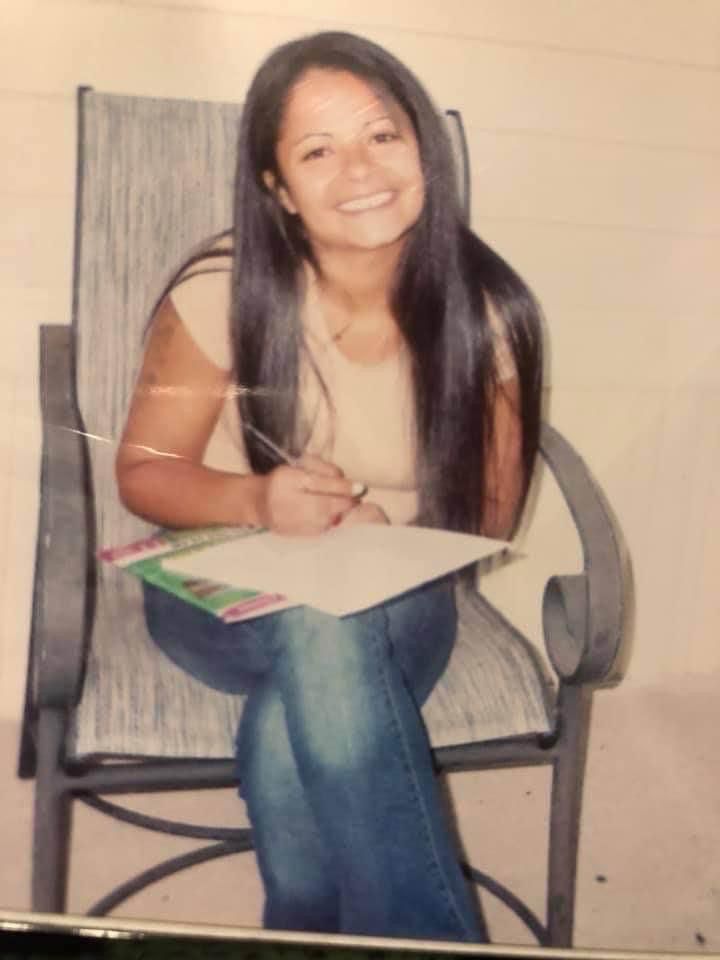

ROBESON COUNTY, N.C. — Sheila Price lives in a state of confusion and unanswered questions over who killed her daughter, Rhonda Jones.

“If you would ever have met Rhonda you would have met one of the biggest hearted people in this county,” Price says.

April will mark four years since the small Robeson County community of Lumberton was shocked by the discovery of Jones' body in a trash can. She was 36.

“Yes, she had a drug problem, but it didn't make her an evil or mean person...she didn't deserve to lay over there in a trash can for days,” Price says.

Jones was a mom, leaving behind five children.

But her death wasn't the first in this area. It wasn't even the second. She was one of three women found dead blocks apart within weeks of each other in 2017.

That's not all they have in common.

“For all three deaths to come back undetermined, I mean you can't find something on these three bodies?,” Price says.

While Jones' death may be undetermined many deaths of Native Americans aren't. The state says there are around 90 unsolved cases of women and children missing or murdered since 1994. And there's nowhere else where the issue plays out more than in Robeson County.

Robeson County is one of the most diverse counties in the United States as 42% of residents are American Indian, 31% are white, 24% are Black, and 9% are Hispanic.

Another statistic that cuts along racial lines is that more Native Americans have their lives cut short.

“There's a sickness in Robeson County that needs to be healed,” Jane Jacobs says.

Jacobs is from Robeson County and a member of the Tuscarora Nation.

The Tuscarora is one of many tribes in the county. The largest tribe is the Lumbee, which is recognized by the state, but not the federal government.

“All of these tribes are begging for help,” Jacobs says.

The sheriff's office says it has investigated 285 deaths, not all classified as homicides, on county land since 2008. More than half of the people who died were Native American. Advocates point out the number of missing and murdered Native Americans could actually be much higher because law enforcement doesn't always know if someone is indigenous, so they don't get identified as such in the police report.

Jacobs' sister, Katina Locklear, was found dead in 2018. She was gang-raped.

Jacobs, who is on the North Carolina board of Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women, says there is a lack of opportunity in Robeson County.

“There's no jobs. There's nothing here. It's like being on a reservation out west where you don't have a lot of resources,” Jacobs says.

Just under a third of the county lives in poverty, which is more than two times the state average.

Brittany Hunt and Chelsea Locklear chronicle indigenous people who have been killed in Robeson County for their podcast The Red Justice Project.

“These women are not really getting justice. They're not getting their faces in the news and the police, in some instances, are not devoting resources to solve their cases,” Hunt says.

The man in charge of solving the cases in Robeson County is Sheriff Burnis Wilkins. The county often ranks as the most dangerous in the state.

“Frankly it's embarrassing...folks would ask where are you from, and I would mention Robeson County, and they'd have this grimace on their face, and that was the thing they would talk about, 'oh lord, what about the crime there?' " Wilkins says.

Wilkins, who spent decades in law enforcement, left retirement in 2017 to run for sheriff. He was sworn in a little over two years ago. He says drugs, guns, and gangs are the driving factor for the deaths.

“What I'm trying as the sheriff is bring those stats down,” Wilkins says.

But he runs an office with a checkered past.

In 2005 the State Bureau of Investigations and U.S. Attorney's Office led an investigation that resulted in 22 people from the office, including the sheriff at the time, charged with crimes from kidnapping to drug trafficking to money laundering. It became known as Operation Tarnished Badge.

“We're still having to build that relationship. It was detrimental to the county at the time. It was not only known locally, it was known nationally,” Wilkins says.

Wilkins says he reorganized the office, collaborated with the federal government to combat violent crime, and created a cold case team of retired detectives to close some of the unsolved homicides. He also says a majority of his staff is Native American.

Hunt says federal recognition of the Lumbee Tribe could bring in needed dollars and resources. While law enforcement support is critical to combat the crime, she says there's a silent killer that's been stalking Native Americans for centuries: history itself.

“This isn't an epidemic because an epidemic is relegated to time...it has a definitive beginning and end. This is an issue that began with colonization,” Hunt says.

Robeson County's struggles are not new. In the 1950s the county had separate water fountains, one for whites, one for blacks, and one for natives. And in the 1990's Julian Pierce, a Lumbee civil rights activist running for a judge position, was slain.

The county also isn't unique.

According to the National Institute of Justice, more than four in five American Indian women nationally have experienced violence, more than half have experienced sexual violence, and native women in some counties face murder rates more than 10 times the national average.

Stephanie Jacobs' cousin Lauren Holmes was found dead not far from where she lived outside Pembroke in Robeson County. The mother of three was killed around eight years ago. Her killer hasn't been arrested.

“I just feel like indigenous people have been overlooked worldwide,” Jacobs says.

Price continues to try and get answers to how her daughter died. She started a victims support group on Facebook called Shatter The Silence.

“I don't know how much more fight I got in me. I don't know how much more I can take,” Price says.

There is a $40,000 reward for information related to the deaths of Rhonda Jones and the two other women found dead, Christina Bennett and Megan Oxendine. You can contact the FBI at 704-672-6100 if you have information.

If you have information about Lauren Holmes' death, you can contact the Robeson County Sheriff's Office at 910-671-3100.