The deadline is fast approaching for the Republican-led General Assembly to redraw North Carolina’s political maps.

Lawmakers have until about Nov. 5 to finish redistricting. They’re about two weeks into the process of drawing new district maps for Congress and the legislature. The schedule for redistricting is so tight because candidate filing for next year’s primaries is Dec. 6, so the maps need to be done a month beforehand.

The primary elections are March 8, but past state primaries have been in May. That’s left many wondering why the legislature doesn’t just delay the election to have more time to draw the maps and gather public comment before they’re approved.

“This is compressed, and it doesn’t have to be,” said Bob Phillips, executive director of Common Cause North Carolina, an advocacy organization that has lobbied for restricting reform.

But the redistricting committees have shown no sign of slowing down or changing the deadline.

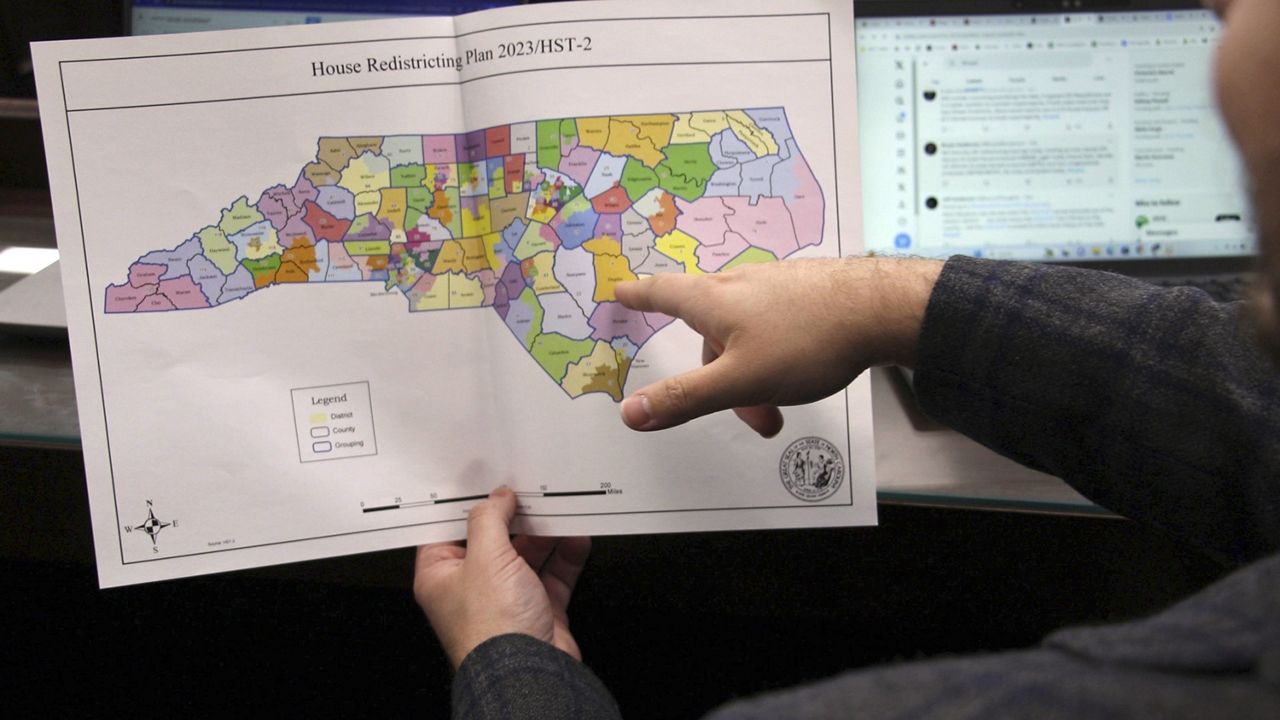

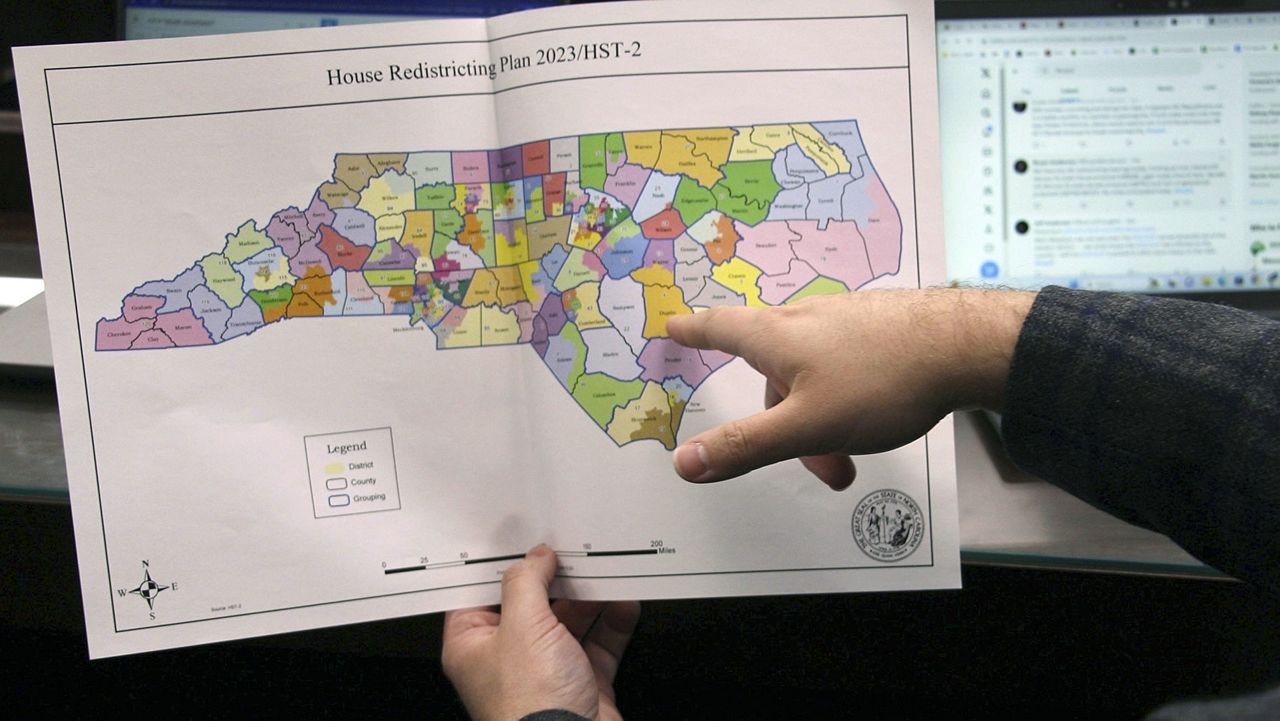

Members of the state House and Senate are working on the new maps in two open committee rooms, with computer terminals set up to live stream as elected officials work on the new maps. It’s similar to the court ordered process from 2019, when a judge sent lawmakers back to the drawing board.

But this is the first time redistricting is happening in a more public manner without a court order. Typically, in North Carolina the maps have been redrawn once a decade behind closed doors. That’s been the same no matter what political party was in power.

“Compared to the past history of redistricting, it’s fairly open,” said Michael Bitzer, a political scientist at Catawba College who just published a book on the history of redistricting in North Carolina.

“You’re dealing with the most political activity in America,” Bitzer said. These maps could dictate who controls the General Assembly and who gets elected to Congress, just based on where the lines are drawn.

That history is one of political and legal fights over gerrymandering, the drawing of maps to keep people of one race or political party in power.

The last time Republicans led redistricting in the General Assembly, the maps ended up at the center of legal fights for almost the entire decade.

“Tell me what the final maps are,” Bitzer said. “That’s the great unknown now.”

The way the process is working so far this year, the computer terminals where legislators are drawing the maps are streaming online so people can actually see the process. Some sharp-eyed observers have been able to grab copies of maps the lawmakers are working on to analyze them.

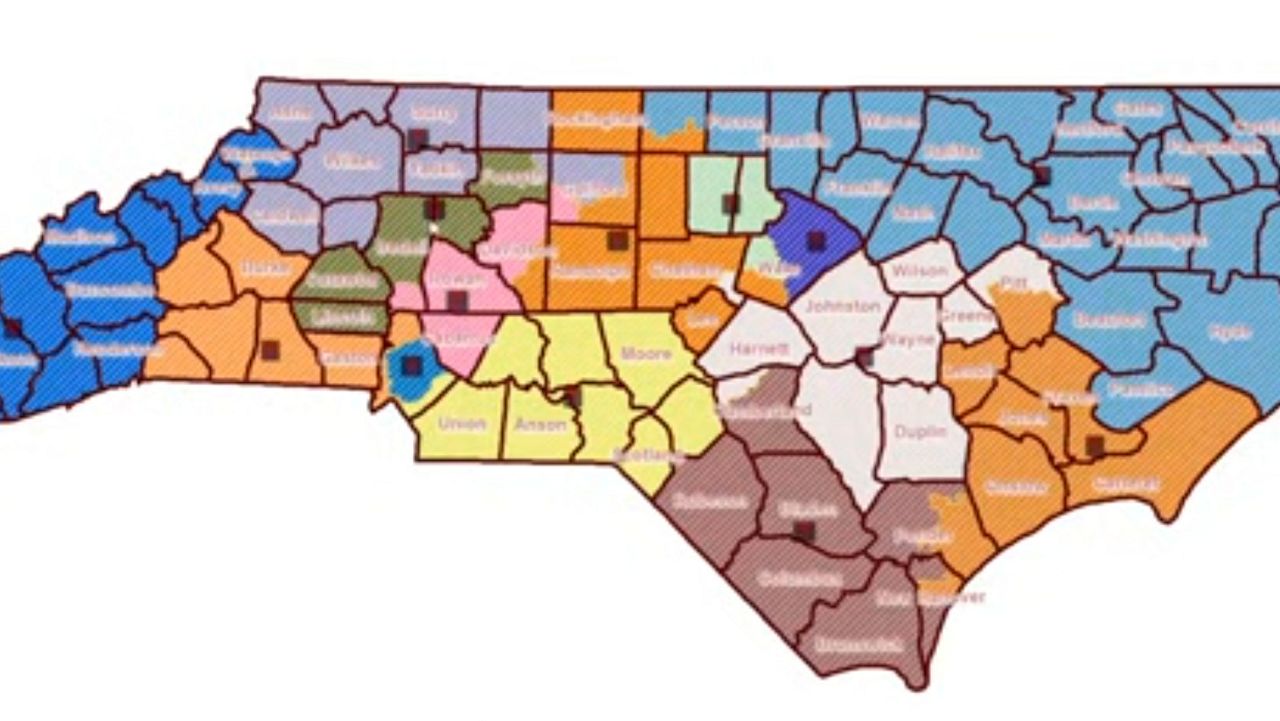

Common Cause N.C., which sued over the maps in the last round of redistricting, analyzed a map Phillips said he thinks will be the likely state Senate map.

“It’s a map that the majority party will maintain control and could take a super-majority,” Phillips said, which means they could potentially override the governor’s veto.

Some of the possible congressional maps seen by Spectrum News 1 break up urban areas like Raleigh or Charlotte, and could potentially dilute the power of Democratic voters.

Bitzer said he thinks the maps should come out this week. But the process once they have drafted the maps is still not clear. Republicans in charge of redistricting have said they are planning for one public hearing in Raleigh.

Republican-led majorities in the House and Senate will have to approve the redistricting maps for the legislature and Congress, which includes a new seat in the U.S. House of Representatives.

“The big question in my mind,” Bitzer said, “is, how many lawsuits will be filed the day the maps are finalized?”

Bitzer’s latest book looks at the long and complicated legal history of redistricting in North Carolina.

Legal battles over political maps in North Carolina have led to the Supreme Court more than once. Most recently, justices on the Supreme Court ruled that issues over partisan gerrymandering were not a matter for the courts based on North Carolina’s maps.

More lawsuits this year sound like a foregone conclusion. The General Assembly committees in charge of redistricting decided to not use voting history and race data to make the maps this year. But the state NAACP and Democratic lawmakers have already accused the Republican-led committee of violating the Voting Rights Act by not considering race in the redistricting process.

The last time lawmakers were in a public room redrawing the maps, they were under a court order and the judges basically said, “get it right or we will draw the maps,” Phillips said. They don’t have that pressure this time around.

Phillips said he thinks the legislature will draw the maps how they want to and “take a gamble with the courts.”

When lawsuits over this latest round of maps get filed, it’s possible that the plaintiffs will ask the courts to delay the primary elections.

“Unless there’s egregious maps,” Bitzer said. The courts “would let the process play out with maps that are being challenged.”

He said the plaintiffs in any lawsuits would argue that the maps are not fair. But the word “fair” can he hard to define. Does it mean competitive districts? Does it mean proportional outcomes for the political parties?

“In politics, oftentimes ‘fair’ is a four-letter word,” he said.